Ken Bolton, A Whistled Bit of Bop (Vagabond Press )

I recently heard a British podcaster describe Louis MacNeice as ‘a highbrow ordinary bloke.’ The implied combination of approachability and erudition struck me as a spot-on description of Ken Bolton in these poems.

As the book’s biographical note tells us, Bolton is a prolific art critic and journal editor as well as a poet. As if to emphasise his intimidating high-browness, the back cover blurb speaks of poetic abstraction and lists members of a ‘pantheon’ who appear in the poems: a timid reader who wasn’t sure who Ashbery or Berrigan are (note the use of second names only – the highbrow equivalent of Cruise and Nicholson), or had never heard of F T Prince or Peter Schjeldahl, might quail.

It’s true that the poems fairly bristle with erudite references. But when one turns to the endnotes for help, here’s part of what they say the second poem in the book, ‘Europe’:

As with many of these poems there are references to art – to Winckelmann, Mengs, Jacques-Louis David – but as the joke is that they are so little thought of now it would be perverse to explain them here.

I stopped worrying about my ignorance, and started getting the joke.

In these poems, an ordinary bloke hangs out in cafes people-watching, or stays up late writing to his adult son on the other side of the planet, broods about friends alive and dead, meditates on art and poetry, and (so it generally feels) somehow lets the flow of his mind find its way onto the page. It’s a lively, questioning, self-conscious and sometimes self-mocking mind. You really don’t need to know who Winkelmann is to have fun reading ‘Europe’. Probably it’s more fun for better educated readers, but that’s not a reason to be intimidated.

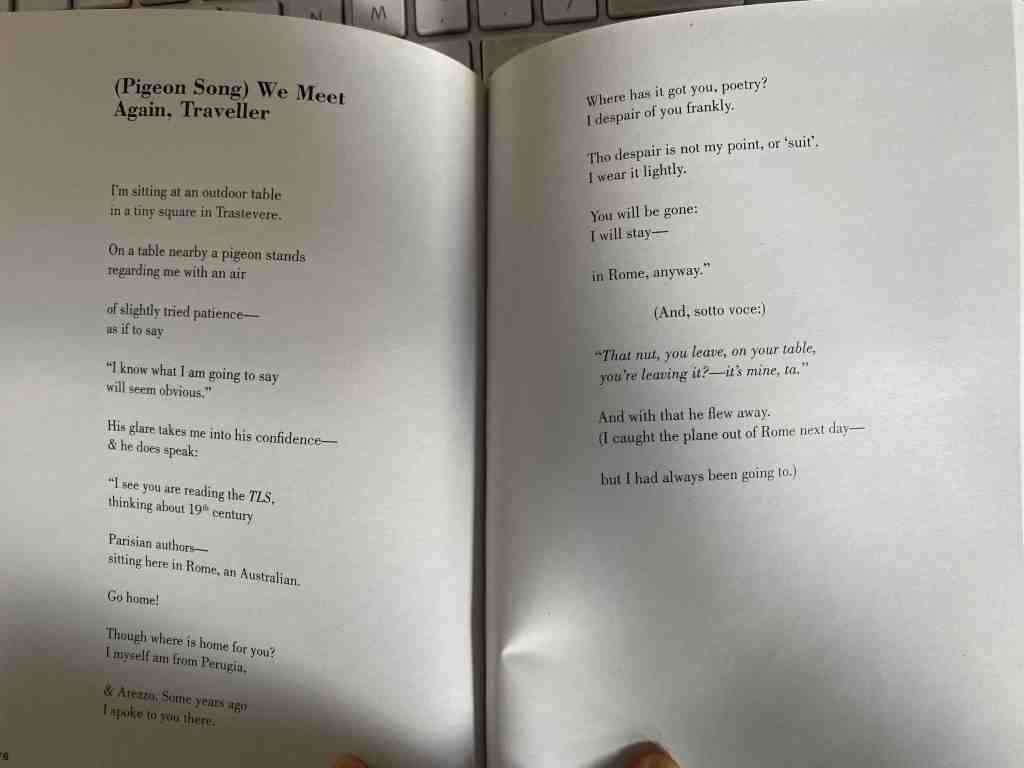

I loved the whole book, but I’ll keep to page 77*. It’s the right-hand side of the spread containing ‘(Pigeon Song) We Meet Again, Traveller’ which, by sheer good blogging fortune, is the shortest poem in the book. Click to enlarge this image:

Not strictly part of the poem, there’s an endnote:

Pigeon Song: a white pigeon with reddish brown flecks on it & around one eye. Strangely the bird had no accent, & spoke in English.

It’s a quietly comic poem in which an Italian pigeon questions an Australian poet about his life choices, after which both pigeon and poet do what they would have done if the conversation hadn’t happened. I hope I won’t make it any less enjoyable by doing a little ‘slow-reading’. With a lovely light touch, it airs some serious issues.

First the title. Its complexity is explained by yet another endnote: the words in brackets, ‘Pigeon Poem’, were a working title, and ‘We Meet Again, Traveller’ is the title finally settled on. Showing his working in this and other ways is one of the things I love about Bolton’s poetry: he lets the reader in on his process. Apart from the title, there’s not a lot of that in ‘We Meet Again, Traveller’. The comic endnote makes up for that absence a little: it implies that the fantasy is based in a real-life moment, and suggests that Bolton may have considered having the pigeon speaking in Italian or with an accent, but – happily – rejected both options.

The action of the poem takes place, typically, in an intellectual ambience. Bolton is sitting at a cafe table in Trastevere, a cool part of Rome that’s home to four or five academic institutions, where sitting at a table reading a literary journal wouldn’t stand out. (As even middlebrow ordinary blokes know, the TLS is the Times Literary Supplement.)

But there’s nothing rarefied or highbrow about the pigeon. Who among us, sitting alone at an outdoor table, hasn’t felt judged by a beady-eyed pigeon (or ibis if you live in Sydney)? This particular judgmental pigeon voices something of the complex unease of being a settler Australian poet, deeply meshed in European culture with an unresolved relationship to the actual land where one lives:

I see you are reading the TLS,

thinking about 19th Century

Parisian authors –

sitting here in Rome, an Australian.

Go home!

London, Paris, Rome, Australia, past and present: it’s complex. I’m reminded irresistibly of a music hall ditty I loved as a child (and which, as a complete irrelevance, I once heard the late Dorothy Hewett sing):

Why does a red cow give white milk

when it always eats green grass?

That's the burning question.

Let's have your suggestion.

You don't know, I don't know, don't you feel an ass?

Why does a red cow give white milk

when it always eats green grass?

The pigeon then asks a key question with characteristic Boltonian (Boltonic?) lightness of touch.:

Though where is home for you?

If you are so immersed in European culture, is your home in a physical location or in a less tangible ‘place’? As in the music hall song, the burning question goes unanswered.

The pigeon knows where its home is, though it too has travelled. Then:

and Arezzo. Some years ago

I spoke to you there.

This may be referring to an earlier Bolton pigeon-poem that I haven’t read, or to a time when he visited Perugia in real life, perhaps to study at the Università per Stranieri. (Decades before Duolingo, Perugia was often mentioned among Australians of a certain age and education as a place to go to learn Italian.) The content of that earlier conversation, whether the subject of an earlier poem or not, was evidently the Bolton’s poetic aspirations:

Where has it got you, poetry?

I despair of you, frankly

But then, having dipped by pigeon-proxy into the well of settler-anxiety, self-doubt and possible despair, the poem returns to lightness. (I’ll just note in passing that I don’t understand the word ‘suit’, or why it’s in inverted commas – any help welcomed in the comments.) The pigeon, dropping its role as cultural challenger, asks the question that’s actually on any judgemental-looking pigeon’s mind. And both pigeon and poet fly away, as they were both going to anyway.

The poem consists of eighteen stanzas, most of them couplets. I can’t say much more than that about the form, except it’s good to notice the use of rhyme in the last third of the poem: stay, away, sotto voce, away, day. Reading those lines aloud, the rhyme creates a sense of relief that the awkward conversation is over: things flow easily. The pigeon’s sotto voce couplet about the nut and the final line both depart from the rhyming flow, suggesting that bird and poet both now exit the staged conversation.

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, where it is my great joy to live, as a settler Australian who tries to remain aware of unceded Indigenous sovereignty. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land.

* My blogging practice, especially with books of poetry, is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77.

Thank you for reviewing a Ken Bolton book again (your third review of a Bolton book).

This is an insightful, wonderful discussion of “(Pigeon Song) We Meet Again, Traveller.”

Another possible way to describe what you accurately call Bolton’s “lightness of touch” would be Boltonesque, and then there’s Boltonny also, and Boltonsodic.

As for why ‘suit’ in the poem is in those inverted commas, just the fact that you ask the question is something of an answer. It makes the reader pause, wonder about the word — which pause would likely not have happened without that punctuation.

Your references to the Boltonian “lovely light touch” while also airing “some serious issues” (which Bolton definitely does) seems to me to be relevant to why Bolton wants to suggest that despair is not his point, or ‘suit’ — that is, if it IS a suit then he will wear it lightly (in this poem) and while it MAY fit (like a suit), despair is not the poem’s point. (And I go back to the last stanza: “”Where has it got you, poetry? / I despair of you frankly.”)

There are many other reasons one might speculate about why ‘suit’ is the only word in the poem to receive that punctuation.

Thank you again for writing about Ken Bolton.

John Levy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John. I love your reading of ‘suit’. One further thought that occurred to me is that the pigeon is aware that as a bird he wouldn’t wear a literal suit, and nor would he play cards involving literal suits, so he self-consciously signals that he speaks metaphorically. And you put it very nicely: he wears it lightly, despair is not the poems main point

LikeLike

suit – as in a card game like 500 – diamonds or hearts, clubs or spades – to follow suit…

this morning awaiting a bus i was joined by a seagull. It cast its eye at me as I read an Egyptian activist’s collection of essays and tapped one of its feet drawing my attention to the fact that the foot was in fact missing. It moved closer and closer. I had nothing to offer it. As other people approached along the pavement it flew away – wings totally intact and its flight as fluid as that of any other seagull. The next time I looked up it was again at my feet. And as I stood – my bus coming – again a smooth soaring away.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder what the seagull was trying to say to you, Jim

LikeLike

Yes, well so was I – wondering what it was trying to say to me. I asked several times – it tapped its stump – which, maybe, was Morse Code? Which I can’t recognise/read – in truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Three books by John Levy, and November verse 10 | Me fail? I fly!