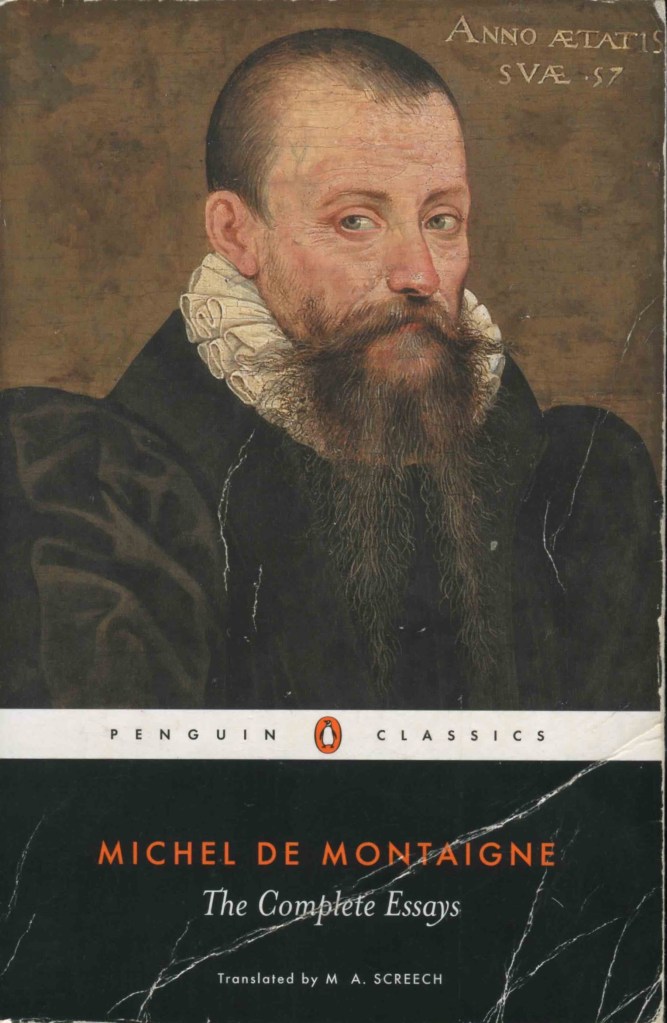

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics 1991, translated by M. A. Screech)

– part way through Book 3, essay 5, ‘On Some lines from Virgil’ to part way through Book 3, essay 10, ‘On restraining your will’

This post was due more than a week ago, but life in general made other plans for me. With a couple of lapses, though, I have consistently read four or five pages of Montaigne’s Essays each morning.

I won’t even try to summarise what I’ve read in the last six weeks. I’ll just mention that ‘On some lines from Virgil’ continued to be fascinating on the subject of sex and gender; in a piece with the innocuous title ‘On coaches’ Montaigne denounces the atrocities of the Spanish colonisation of Central and South America; in ‘On the disadvantages of high rank’ he pities those whose social position means no one will disagree with them, because they are deprived of the joys of conversation.

And then there’s ‘On vanity’, a long essay that made me fear age-related cognitive decline was catching up with me. As with many of the essays, ‘On some lines from Virgil’ being a prime example, this one’s title gives you no idea of its true subject. But in this case, I couldn’t tell if it even had a main subject. He writes about travel, about death (a lot about death), about how much he loves Rome. He explains why he’s glad he has no sons. He quotes at length from the document granting him Roman citizenship. He’s like a dog snapping – in slow motion – at whatever fly of an idea crosses his mental line of vision. But in the middle of it all, he has one of the passages that remind you that he is inventing the form of the personal essay – and k ows exactly what he’s doing:

There are works of Plutarch in which he forgets his theme, or in which the subject is treated only incidentally, since they are entirely padded out with extraneous matter … My God! what beauty there is in such flights of fancy and in such variation, especially when they appear fortuitous and casual. It is the undiligent reader who loses my subject, not I. In a corner somewhere you can always find a word or two on my topic, adequate despite being squeezed in tight. I change subject violently and chaotically. My pen and my mind both go a-roaming. If you do not want more dullness you must accept a touch of madness.

‘It is the undiligent reader who loses my subject, not I.’ I’ve been put in my place.

He defends his lack of coherence by applying to himself Plato’s description of a poet as someone who:

pours out in rapture, like the gargoyle of a fountain, all that comes to his lips, without weighing it or chewing it; from him there escape things of diverse hue, contrasting substance and jolting motion.

I don’t know that anyone seriously thinks that’s what poets do, but the idea that a reader needs to be ‘diligent’ to do justice to some writing has still got a lot of life in it, probably even more than it did in Montaigne’s day. He goes on to say he doesn’t stitch things together ‘for the benefit of weak and inattentive ears’:

Where is the author who would rather not be read at all than to be dozed through or dashed through? … If taking up books were to mean taking them in; if glancing at them were to mean seeing into them; and skipping through them to mean grasping them: then I would be wrong to make myself out to be quite so totally ignorant as I am. Since I cannot hold my reader’s attention by my weight, manco male [it is no bad thing] if I manage to do so by my muddle.

So, just as he’s getting tetchy with us for being lazy, he acknowledges that he’s a pretty lazy reader himself. And having claimed that his apparent incoherence is actually poetic brilliance, he now calls it a muddle.

Oh, and in the middle of all that charming back-and-forth between grumpiness and self-deprecation, there’s this lovely, enigmatic line:

Poetry is the original language of the gods.

I’m not sorry I gave up French Honours in 1968 because I found Montaigne almost as unreadable as Rabelais. I’m enjoying reading him now, in translation, much more than I possibly could have in the original when I was 22.

This blog post was written on Gadigal-Wangal land, where the days are getting hotter and more humid. I acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation.