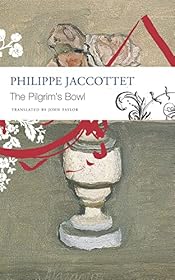

Philippe Jaccottet. The Pilgrim’s Bowl (2001, translated by John Taylor 2015, Seagull Books 2022)

This is a short book by a poet who is completely new to me about an artist whose work I have never seen. It was a Christmas present, a book I wouldn’t have dreamed of buying for myself. I enjoyed it a lot.

Philipe Jaccottet (1925–2021) was a Swiss poet who wrote in French, one of only fifteen writers to be included in the canon-defining Bibliothèque de la Pléiade while still alive. His English-language Wikipedia page is extremely sparse, but French-language Wikipedia is a different thing altogether. His expansive page there includes this (as rendered by Google Translate):

Jaccottet writes that the poet is no longer ‘the Sun […] nor a son of the Sun; nor even a Torchbearer or a Lighthouse’ (he therefore rejects the image of the ‘poet-prophet’): the task of this ‘anonymous one […] dressed like any other anxious man’ is to try to ‘paint’ the world ‘so wonderfully’ that his work would be able to distract Man from his fear of death.

In The Pilgrim’s Bowl, Jaccottet turns his attention to the work of Italian painter and printmaker, Giorgio Morandi.

Though I’ve never seen an original work by Morandi (1890–1964, Wikipedia page here), I know a little more about him than about Jaccottet. The Emerging Artist did a beautiful drawing when at Art School that was copied, she told me, from one of his paintings, and the great cartoonist Jenny Coopes, taking up ceramics late in life, created a set of Morandesque objects which we now own. (For the benefit of readers who don’t know Morandi’s work: this photo does not capture anything of its austere, dreamlike simplicity.)

After reading this 66-page book with its dozen images, I feel that I know – and like, and admire – both these people much better. Jaccottet does not present as an art critic. He is not out to describe Morandi’s paintings, but to explore what he calls the enigma of the powerful emotion they create in him. This is from page 3:

It is not surprising to be stirred by the view of a mountain, the ocean, a sunset, a big city; or by the imminence of a war, the nearness of a face, the death of a close friend. And therefore, consequently, by their representation in a painting, poem or narrative. But with this artist: those inevitable three or four bottles, vases, boxes and bowls – what apparent insignificance, what ludicrousness or nearly so (and all the more so when the world seems about to collapse or explode)! And how can you dare claim that such a painting speaks a more convincing language to you than most contemporary works of art?

He approaches the enigma from different angles, ‘as naively as possible’. Which means he goes down tangent after tangent, and somehow enriches our sense of Morandi’s work.

Noting that Pascal and Leopardi were Morandi’s favourite authors, he spends fascinating pages discussing them. He riffs on snippets of Morandi’s biography. He catches fleeting associations – remembering that Morandi would let dust settle on his paintings, he thinks of the ‘sandman’ and then of the Sleeping Beauty, which gives him a way of talking about ‘the unchanging light bathing Morandi’s paintings’:

It never sparkles or glares, never flashes or breaks through clouds, even if it is clear as the dawn, with subtle rose and grey hues, this light is always strangely tranquil.

There is much more about that light.

He quotes from Dante and Plato. Acknowledging that he may be a little over the top, he compares Morandi’s still lifes with Vermeer’s paintings of young women and even with classic Madonnas.

Page 47* is the first half of the book’s most tangential tangent. Page 46 ends with this beautifully distilled paragraph:

The more Morandi’s art progresses in terms of deprivation and concentration, the more the objects in his still lifes take on, against a background of dust, ash or sand, the appearance and the dignity of monuments.

Then, abruptly, a parenthesis takes up the next two pages, beginning:

One night not long ago, I remembered a stopover in Ouazazarte, Morocco – rose-coloured sands and yellow sands, windy gusts blowing distant sand up into flags, and those fortress-like buildings shimmering in the excessive light without being mirages, yet barely distinct from the ground on which they had been built – why was this brief glimpse-like vision one morning so poignant?

I don’t know how to summarise this work. You have to be there. Let me just say that when I do get to see a painting by Morandi, I will come to it with eyes, heart and mind prepared.

I wrote this blog post on Wadawurrung land, overlooking the Painkalac River. I acknowledge their Elders past and present.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently. As The Pilgrim’s Bowl has fewer than 77 pages, I’m focusing instead on my birth year, ’47.

Thank you for this marvelous tribute to Jaccottet and Morandi.

There are many translations into English of Jaccottet’s poems and prose. Here is a prose passage, translated by Tess Lewis, from THE SECOND SEEDTIME: NOTEBOOKS 1980-1994:

Around three in the afternoon, the telephone rings. I hear something like a man grunting or grumbling: the silence. This is not a dream. A joke in bad taste? A plea? I’ll never know.

John Levy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John. I have been reading little bits of Jaccottet in French and English. I hadn’t seen that passage – which seems to be a nice example of his humility in the face of experience.

LikeLike

Another book of Jaccoettet’s, somewhat similar to his book on Morandi, is titled Truinas, 21 April 2001. It is a series of meditations on the life, the art, and the death of his friend, the poet Andre du Bouchet. Jaccottet says, of du Bouchet’s poetry that it is incandescent and that du Bouchet “. . .reached in words as few other poets have been able to do, shooting his arrows from a bow strung to its keenest tautness.”

Jaccottet’s own poetry is well worth reading. Here, translated by Derek Mahon (in the book titled Philippe Jaccottet Selected Poems), is a poem from a 1957 book of Jccottett’s that is relevant and moving today:

The Unexpected

I don’t pay much attention to the fiend.

I work and looking up sometimes,

I see the moon before light dawns.

What is left shining of winter?

When I go out before daybreak

snow stretches to the farthest limits

and grass bows to its silent greeting,

revealing what one had no longer hoped for.

John Levy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks again, John. ‘I don’t pay much attention to the fiend’ is certainly a line that speaks to our moment in time!

LikeLike