Christine Dwyer Hickey, The Narrow Land (Atlantic 2019)

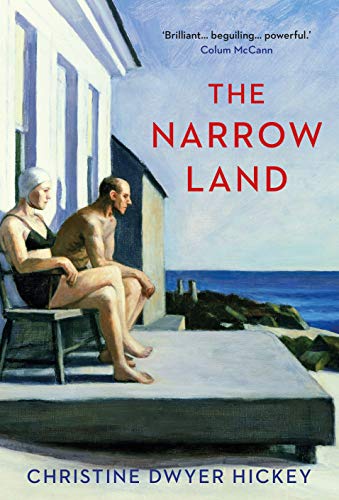

The cover of The Narrow Land features Edward Hopper’s painting Sea Watchers (1952). The back cover tells us the book is about a ten-year-old boy who forms an unlikely friendship with ‘the artists Jo and Edward Hopper’. But nowhere in the narrative itself are we told the names of the two artists, even though many of the man’s paintings are lovingly described and even a reader as ignorant about US art as I am could recognise some of them (admittedly with help from Duck Duck Go) as Hoppers. Nor is there an afterword or acknowledgement to clarify the story’s relationship to historical fact.

I don’t know what to make of that, since it looks as if a significant dimension of the book is a fictional depiction of Hopper’s practice and the Hopper marriage. In particular, to judge from Josephine Hopper’s Wikipedia entry, it’s likely that the narrative draws on her copious journals recording her bitterness and their stormy quarrels. The character’s journals are mentioned, but Josephine Hopper’s are not.

The Hoppers-not-Hoppers, she in her sixties and he quite a bit older, have a terrible relationship. They are at their Cape Cod house for the summer in the early 1950s. He is stuck, searching for inspiration. She lives in his shadow, resents his failure to support her work, nags at him to get on with his own, is hyper-alert to possibilities that he will be attracted to other women, and relentlessly picks fights with him. He is relentless right back at her. They’re not people you want to be around.

Ten-year-old Michael comes into their lives. He is a German war orphan, possibly Jewish, brought to the US and adopted by a working-class couple in New York, spending the summer with a benefactor who is the artists’ neighbour.

Relationships develop among these characters, including Michael’s complex host family. The narrow land of the title refers literally to Cape Cod, as in this map. It also refers, I think, to the narrowness of a non-combatant USer’s world-view: Michael’s hosts are unable to imagine the magnitude of what he has endured (which he experiences now as nightmarish flashes of memory). The narrowness is also there in the constrictions that society places on the artist, and the claustrophobia that ‘Mrs Aitch’ rails against in her marriage. Perhaps it refers also to the limits imposed on people’s lives in the wake of the Second World War – partners, parents and siblings are still being mourned, and returned soldiers wander through the narrative like wraiths.

For the most part, this isn’t a pleasant read. I found Mrs Aitch especially painful – like Pansy in Mike Leigh’s Hard Truths, her bitterness is unremitting, but she lacks Pansy’s biting wit. Unlike Pansy though, she finds temporary relief in connection with children – Michael and his obnoxious host Richie – where we get to see her in a more positive light. Also unlike Pansy, she has a moment when her intolerant discontent saves the day.

Having just described Richie as obnoxious, I feel obliged to say that even though almost all of the characters are unlikeable, most of them have moments when we see an underlying pain. We come to see Richie in particular as tragic.

Page 78* turns out to be a good example of my pervasive frustration. It’s near the start of the novel’s second section, titled ‘Venus’, in which we realise that ‘he’ – Hopper-not-Hopper – is searching for a woman he glimpsed the previous summer, as he feels that she will inspire him now. (Spoilerish note: he does find her, but it doesn’t work.) On this page he remembers the day that he found her:

She was standing in the doorway of a house, a man standing on the threshold, maybe leaving or maybe hoping to get inside.

He’d driven by and pulled in further along the street. Then he walked back past the house. There had been a bush by the gate, tangled and dried up from the heat, a lawn, yellowed by neglect and the ravages of a long summer.

There’s a description of her clothes and a snippet of overheard conversation, then:

He had walked on for a couple of minutes. then crossed the road to return on the opposite side, his head tilted as if he were searching for the number of a door. As he came closer to the house, he saw her lift her hands and put them under her hair, which was a whiter shade of blonde. Then she flipped it all up, holding it for a few seconds to the back of her head. He could see the damp patches of sweat stamped into her armpits and the outline of her long neck, the soft curve where it joined her shoulders. She dropped her hair and her face lifted upwards. The blue blouse. The light on her face. He couldn’t figure out if it was pouring into her or pouring out of her. He thought she looked sanctified. Then he thought she looked the opposite.

He rushes home and drags out his easel:

He laid it down: the street, the house, the figure of the girl in the doorway, the figure of the man alongside it with one foot on the step, the lawn, the gate, the tangled bush.

This is emphatically an account of a particular artist’s creative process. It’s as if the novelist sets out to imagine for us how Edward Hopper created one of his paintings, but then – for legal reasons, perhaps, or from simple respect for the unknowability of the real man – pulls back from acknowledging that that’s what she’s doing. The understated eroticism here plays nicely into the portrait of the artist’s marriage: his wife (never named) realises that she is not the model for the woman in the painting, and is furious.

On the way to the meeting: We read The Narrow Land along with Richard Russo’s Everybody’s Fool. Just before the meeting I’m noting some things the books have in common:

- they both have dogs that make a mess of cars – the disgustingly incontinent Rub in Everybody’s Fool, and Buster in this book who leaves a car ‘looking like a feathered nest’

- characters read books: Sully in Everybody’s Fool remembers as a boy reading the beginning of a book we recognise as David Copperfield (Dickens), and discarding it; Michael in this book reads The Red Pony (Steinbeck) and Tom Sawyer (Twain) and takes them in his stride

- Class looms large: when Michael’s working-class foster parents turn up we suddenly feel grounded in honest relationships; when Sully’s son turns up in the other book, we’re away with the abstractions of middle-class life.

After the meeting: The books had to compete with the pope’s funeral on the TV, but we still had an interesting conversation.

I think we were all a bit perplexed by A Narrow Land – not quite sure where its focus is. The person who had first proposed it, an artist herself, kicked the conversation off by saying that she was disappointed the book had so little to say about Hopper’s process, and in a way we circled around that central absence for the rest of our conversation.

One other person shared my unease about the relationship between the fictional characters and the historical persons. Others had no problem with it, and I still find it hard to say precisely what my problem is. Our host produced a hefty volume of Hopper’s work and we tried to pin down the paintings he works on in the book. No one claimed to have enjoyed the book unreservedly, though I think we all found some joy, or at least pleasure, in it. No one was much interested in trying to compare the two books.

We met on the land of the Bidjigal and Gadigal clans of the Eora nation, overlooking the ocean. I wrote the blog post on Wangal and Gadigal land. I gratefully acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for this beautiful country for millennia.