Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway (1925, Penguin Classics 2020)

Since taking nearly two years to read Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu six years ago, I’ve had a classic slow-read on the go most of the time. When I’ve embarked on one of these slow-reads I regularly come across mentions of the book elsewhere. It’s like that with my current project, Mrs Dalloway.

This month, a friend sent me a link to Zora Simic’s article in The Conversation, Trauma memoirs can help us understand the unthinkable. They can also be art. Here’s an excerpt:

Of all Woolf’s novels, Mrs Dalloway is the one most often read as semi-autobiographical and as a reckoning with unresolved trauma: of England’s in the wake of the first world war, and in the novelist’s own life. <big snip> Woolf has long been a lodestar for writers grappling with trauma – in their lives, and on the page, especially women writers.

Reading the first couple of pages, when upper-class Clarissa Dalloway is out in the early morning shopping for flowers and enjoying the life of the London streets, I couldn’t see much trauma. But then the scene broadens and darkens. By page 103, I’m now reading the book as mainly about aftermaths: Clarissa is recovering from an illness and enduring an unhappy marriage; the War and pandemic are still alive in collective memory; Peter Walsh, freshly returned from a decade in India, is still wounded by having been rejected by Clarissa many years earlier; returned soldier Septimus Smith is wandering London’s streets, hallucinating, suicidal, ‘shell-shocked’ and putting his Italian wife Lucrezia through hell. There’s plenty of trauma to go round.

I’m glad I’m reading this book just a few pages a day. It cries out for sharply focused reading, which I can just about sustain for three pages at a time. Read this way, the book is exhilarating. I had thought it was going to be the stream of consciousness of one upper-class Englishwoman. In fact there’s a whole array of characters, and the narrative voice flits among them. I say ‘flits’ because feels as if the narrator is an elf-like creature (I almost see her as Tinkerbell) who slips in and out of people’s minds, sometimes staying for barely a second, sometimes for several pages. Most of the characters are aristocrats of one sort or another, but not all. Lady Bruton’s maid Milly Brush has definite likes and dislikes as she stands impassively while her mistress entertains three gentlemen for lunch. One of those gentlemen is a bluff middle-class man with pretensions – he knows how to craft a publishable letter to The Times but believes women shouldn’t read Shakespeare for moral reasons. And Richard – Mr Dalloway – makes an appearance, buying flowers for Clarissa and resolving to tell her he loves her (which the reader knows is far too little, far too late). And so on. It’s much more complex, and funnier, than I expected.

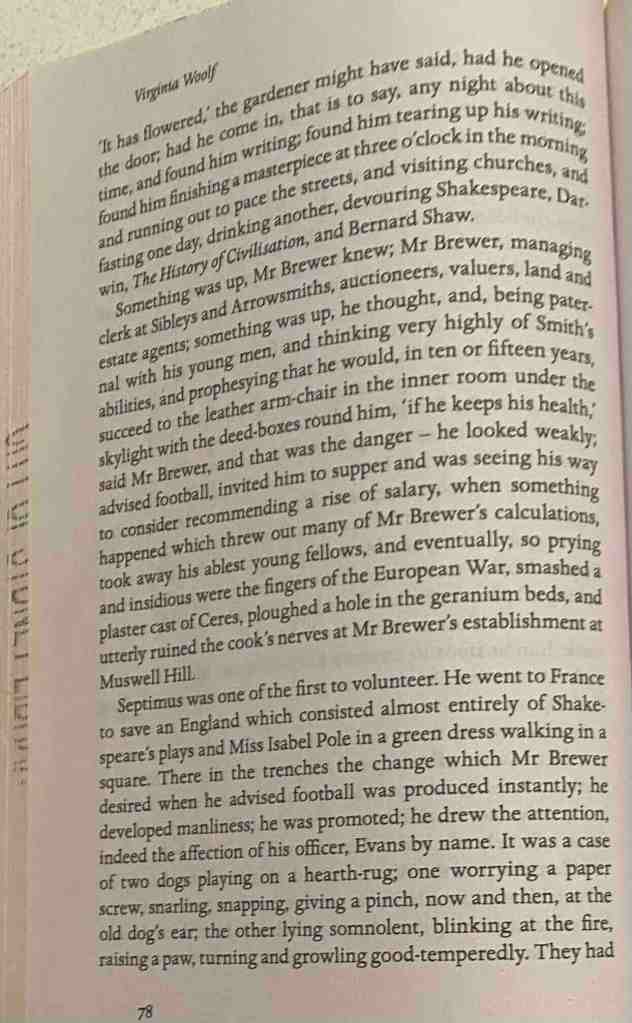

Here’s page 78*:

And because it’s November**, here’s a verse drawn from it and the next page:

November Verse 1: Septimus Smith

He might have made a great accountant

but for Shakespeare, Keats and love

that set him scribbling with his fountain

pen all night. 'You need to tough-

en up, play football,' said his mentor.

War changed everything. He went to

fight in France and made a friend,

a cheerful manly friend, whose end

in Italy was sudden, brutal.

Mrs Woolf says War had taught

him not to feel, to set at nought

such loss. Sublime the total

calm he felt. But, come next year,

the sudden thunderclaps of fear.

I have written this blog post near what was once luxuriant wetland, in Gadigal and Wangal country, where I recently saw two rosellas (mulbirrang in Wiradjuri, I don’t know the Gadigal or Wangal name). I acknowledge Elders past and present of those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.

** Each November I aim to post 14 fourteen line stanzas on this blog (see here for an explanation, though that explanation incorrectly calls my verses sonnets)