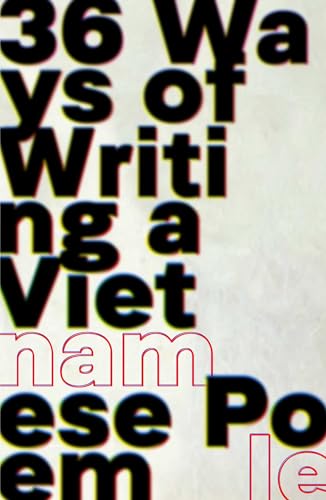

Nam Le, 36 ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem (2023)

I know that I’ve read and enjoyed Nam Le’s first book, The Boat, but I don’t seem to have blogged about it. In one of its early stories, a character who fled from Vietnam with his family as a young child in a dangerously overcrowded boat is now an emerging writer. He resists pressure from all sides to write from within the Vietnamese refugee identity. After several other stories, the book ends with ‘The Boat’, a version of the story the character has been hassled to write. Resist as you may, the collection as a whole seems to say, in the end you will write the kind of thing that people demand from you.

This book of poetry plays with the same dilemma. Interestingly enough, in the acknowledgements, Nam Le thanks Nick Feik, ‘who for years gave my poems a home in The Monthly‘ and goes on, ‘Those poems are not in this book, but they paved the way for these.’ That is to say, Nam Le has not been condemned to write only ‘Vietnamese poems’. He has chosen this task. The poems explores identity, history (including colonial history), autobiography, family relationships. They are full of painful exploration and playful, formal adventure.

Each poem is numbered and named for its ‘way of writing’, beginning with ‘[1. Diasporic]’ and including poems named for their poetic form such as ‘[3. Ekphrastic]’, for their subject matter ‘[12. Communist]’, with puns on their content ‘[Dire critical]’, and so on. Many titles include the word ‘Violence’.

I can’t say that I found all the poems accessible. But I understood and enjoyed more of them than Nam Le’s session at the 2024 Sydney Writers’ Festival led me to expect (my blog post here). I love what J. M. Coetzee says on the back cover. To quote a little:

There is wit aplenty, of a dancing, ironic kind, but the fury and the bitterness that underlie 36 Ways come without disguise, as do its moments of aching love and loss.

The poem on page 47*, is ‘[26. Erasive]’. Normally, I’d photograph the spread where the poem appears and quote at least some of it, but in this case I’ll attempt a description instead.

Beneath the poem’s title is a subtitle in smaller all-caps type, ‘[ERASURE RHYMES WITH ASIA]‘. The rest of the spread consists of what appears to be 46 lines of prose, 23 on each page, that have been almost completely redacted – that is, the pages consist visually of two sets of 23 thick black lines.

There are 25 patches of un-erased text, each consisting of either a single letter or a pair of letters. They can be laboriously piece together to make two sentences:

Left-hand page: N o ar ch iv e is sa fe

Right-hand page: Bu t is t h i s a l l t h er e is to i t.

The hunt through the archives turns up something, but leaves so much unknown.

This is powerfully evocative – especially just now, when the US Department of Justice has released hundreds of pages of the Epstein files completely blacked out. History is written by the victors, and the archives are controlled by those in power.

In the book I hold in my hand, the erased text on the left hand page is just legible. At least, to my eyes it hovers on the threshold of legibility. With a little help and a lot of squinting, I can tell you that the deleted script begins:

Newspaper Articles Almanacs Treatises (Scientific, Political,

Anthropological. Ethnological), Expedition Reports Ships Logs

Royal Proclamations Acts of Parliament Papal Bulls and Breves

Vatican Decrees Edicts Encyclicals Jesuit Relations

and – I’m leaving out the intervening lines – ends:

White Papers Green Papers Letters Patent Land Grants Titles

Medical Records Inventories Accounts Patents Estimates

of Expense Reports Settlement Proposals Petitions Notice

Dictionaries (Bilingual, Trilingual) Treaties Confessions Poems

I’ve bolded the only letters in those lines that are left un-erased.

Many (most?) erasure poems work on a given text to comment on it in some way – like ‘Sacrificed on Altar of Vice’ by Brittany Bentley in a recent Meanjin, or my own little exercise in my blog post on David Adès’s The Heart’s Lush Gardens. That’s not what’s happening here.

Here the underlying text is a list, composed as part of the poem, of the kinds of documents one finds in an archive. The poem enacts the process of sifting through the archives to find information, encountering colonialist-bureaucratic ways of seeing, from property documentation to papal bulls (the infamous Doctrine of Discovery comes to mind). Then, just as one might be feeling a little smug because, after all, I am the kind of person who reads poems, the last almost-erased word is ‘Poems’. Nam Le does not exclude himself from complicity.

That’s the first page. On the second page the erased text is completely illegible. Erasure is complete: we can never know what is hidden from history.

The more I looked (literally) into this poem, the more I appreciated its ingenuity. More importantly, the more I fond myself responding to its emotional and intellectual charge: ‘Erasure rhymes with Asia.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78. When, as here, a book has fewer than 78 pages, I focus on page 47 (I was born in 1947).

I imagine (correctly?) that the title, and something of the approach, is meant to allude to (or perhaps is slightly influenced by) NINETEEN WAYS OF LOOKING AT WANG WEI, by Eliot Weinberger & Octavio Paz. This book, however, sounds much more experimental. Thanks for the review!

John Levy

LikeLiked by 2 people

I thought more ‘Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird’ or ’36 views of Mount Fuji’, but I don’t have any inside information. I hadn’t heard of Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei – thank you for mentioning it, John. I’ve now got it on order from my local bookshop.

LikeLike

Thanks for the review

LikeLiked by 1 person