This is my ninth and last post on books I took with me on my escape from Sydney’s winter, focusing as usual on page 76. I’ve been home for a while, but it takes a while for the blog to catch up with life.

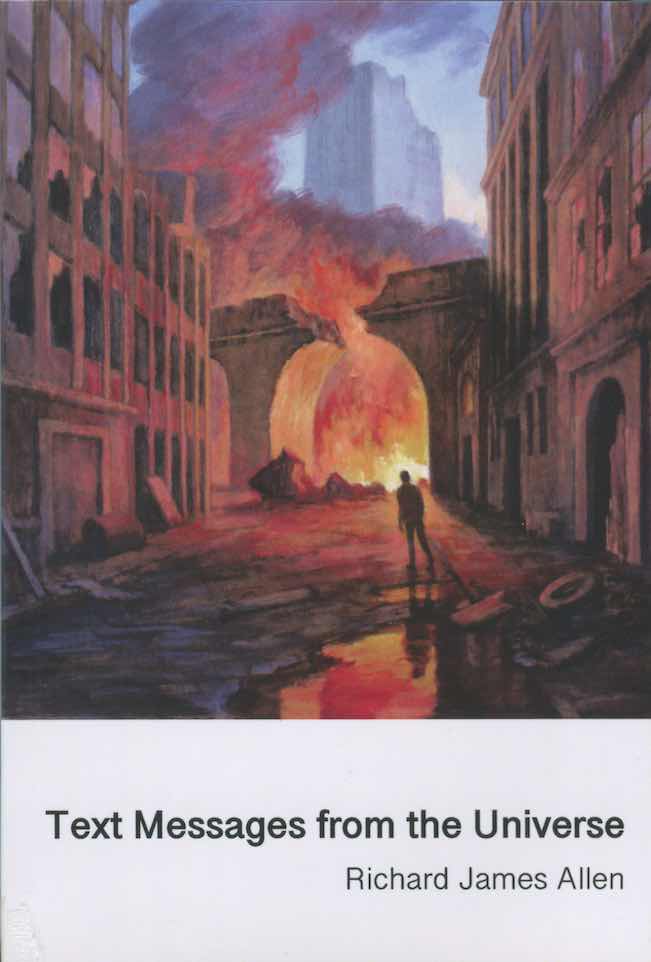

Richard James Allen, Text Messages from the Universe (Flying Island Books 2023)

Like the other titles in Flying Island’s ‘minor works / Pocket Poets’ series, Text Messages from the Universe is a physically tiny book – just 152 x 102 mm. But it’s part of a broader multi-media project.

There’s a movie of the same name directed by Richard James Allen, which is the source of the lavish images of dancing figures that accompany the text (or perhaps, depending on how you see things, that are accompanied by the text). The front cover is from a painting created for the book by 2023 Archibald finalist Michelle Hiscock. The text itself, a single prose poem, is the final work in the multi-volume The Way Out At Last Cycle, which has been three decades in the making (Hale & Ironmonger published The Way Out At Last and other poems in 1985).

The poem is inspired by the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The first, shorter section is addressed to a person who dies in a car accident. In the second section, made up of 49 short parts, the person is lost in a state between death and rebirth, the bardo, in a cycle of dreaming and waking, bewildered, disoriented and panicking. The poetry takes on a weirdly insubstantial quality that is beautifully enhanced by the billowing drapery of the dancers on every page. I haven’t read the Tibetan Book of the Dead – that part of 1960s enthusiasm passed me by – so I don’t know if the poem follows it with any precision, but there’s a wonderful sense of being carried along on a current leading to detached oblivion and then, perhaps, to a new beginning.

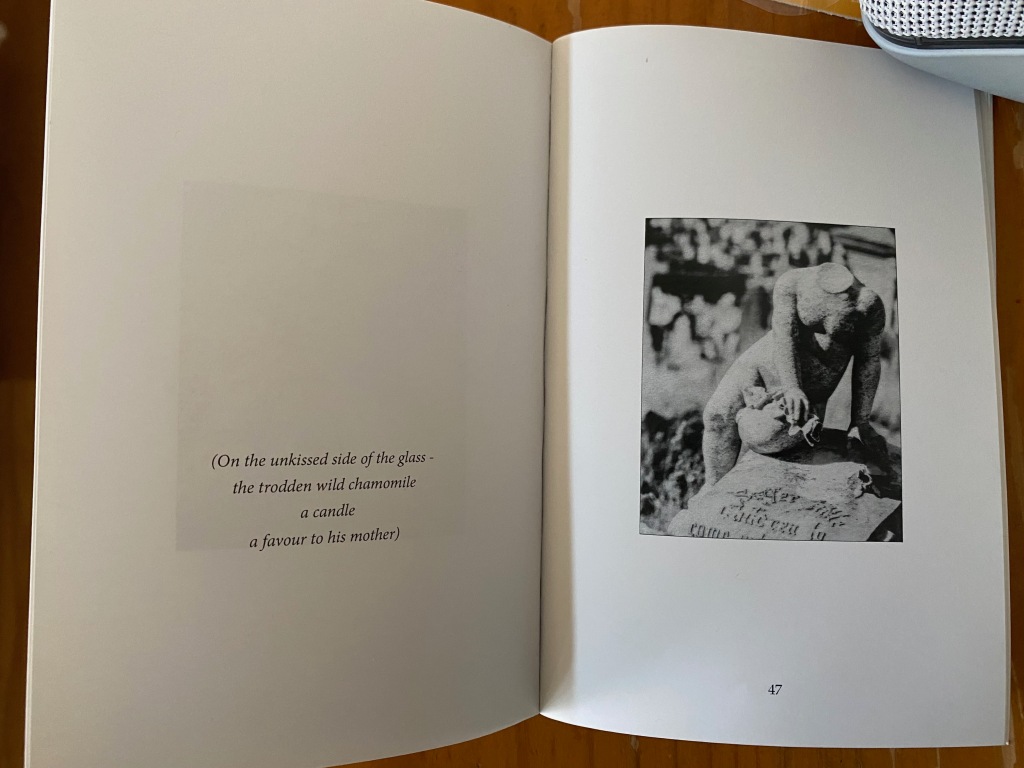

No spoiler intended, but the text messages of the title are revealed towards the end of the poem, in part 46: ‘This is your last moment,’ closely followed by, ‘This is your first moment.’ Part 47 adds this gloss:

As for the rest, Your text messages from the universe seem to be happy to take any form and any language they please. Some of them aren't even text messages, just whispers inside your head.

Speaking as someone who is currently reading Saint Augustine’s Confessions, I’d add they may also come in the form of a child chanting on the other side of a wall.

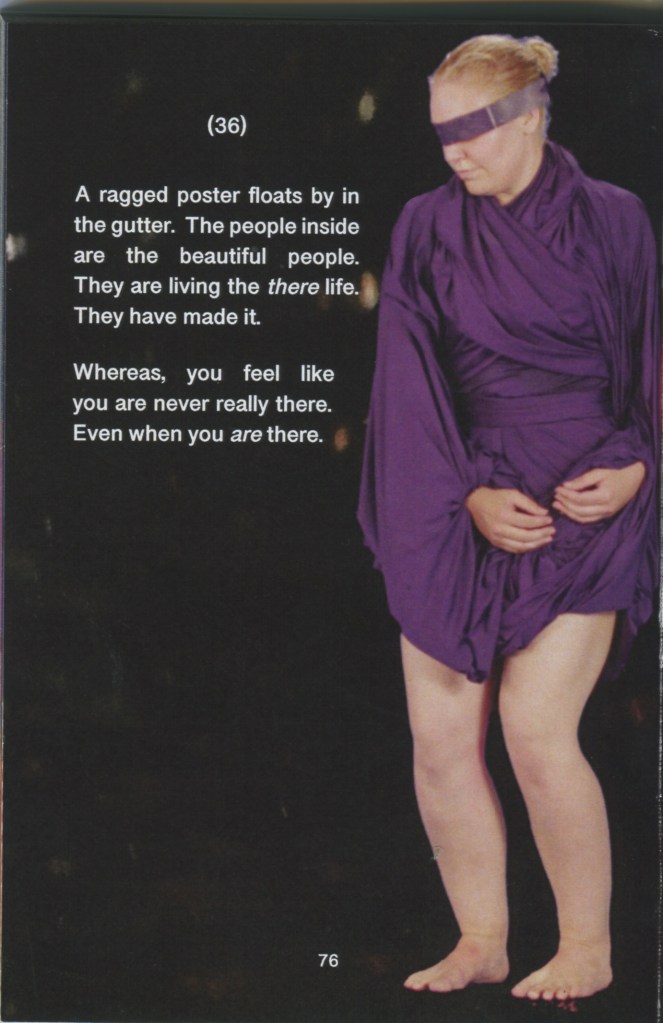

Even while I’m enjoying the poem’s journey in an invented universe (apologies to any of my readers for whom the bardo is as real as purgatory is to some Catholics), my tendency as a reader is to cast around for the kind of actual experience that the invention draws on and possibly illuminates. The short poem on page 76, section 36, rewards this tendency:

(36) A ragged poster floats by in the gutter. The people inside are the beautiful people. They are living the there life. They have made it. Whereas, you feel like you are never really there. Even when you are there.

Incidentally, this is the only image in the book where the dancer is less than elegant, where the fabric is not floating in an ethereal breeze. It signals that, as so often happens, page 76 is a kind of turning point, in this case a low point.

The text offers one of the poem’s many noir-ish images – one of many alleys, gutters and empty lots. The poster is a piece of detritus from the life left behind. In the dream world of the poem, it asserts the substantiality of that life, its thereness. These lines reward my penchant for literalness by drawing on a moment of a kind I imagine we’ve all had: you see a poster for some event and reflect fleetingly that the life represented in the poster is unreal – either that, or it’s part of a reality that you have no part of. This is the moment in the bardo when the newly-dead person is closest to nothingness: it’s the rubbish poster that’s real.

In the years that this poem was fermenting, the bardo attracted the attention of a number of other creators. I’m aware of George Saunders’s multivocal novel Lincoln in the Bardo (2017), which I haven’t read, and Laurie Anderson’s movie Heart of a Dog (2015), for which I just couldn’t stay awake. I had no trouble staying awake on the journey with Text Messages from the Universe.

I’m grateful to Flying Islands Books for my copy of Text Messages from the Universe.