Given the lack of government support for the arts in general and literary magazines in particular, it’s no small miracle that so many of them survive and continue to publish excellent work. I do my little bit, subscribing to three and buying an occasional one-off as the spirit moves me. Then I find time to read them, sometimes falling terribly behind.

Jessica L Wilkinson (editor), Tricia Dearborn (guest editor), Devika Belimoria (artist), Rabbit 31: Science (2020)

Rabbit is a ‘journal of nonfiction poetry’. I don’t subscribe, and I’ve only read one previous issue, Number 10 (my blog post here). Like that issue, this one is beautifully designed – it features gorgeous images made by Devika Belimoria using a mysterious (to me) process involving acrylic paint and macrophotography.

The Science issue is edited by Tricia Dearborn, whose poetry I love. Whereas Tricia’s own science-related poems tend to be accessible to a non-specialist reader (as I have testified in blog posts here, here, and here), some of the poems she has chosen here are dauntingly technical. But one good thing about anthologies is one can skim, though I didn’t skim very much at all.

To give you a taste, here’s a sampling of opening lines:

From ‘Perpetual Motion’, a series of prose poems by Amit Majmudar:

Amazonian nomads, last studied in the 1940s in Brazil (in that anthropologist's recordings of their dirges, you can hear chainsaws buck alive in the background), had a religion based on the quest for eternal life – only immortality wasn't a quality, as it is for us, but a place they had to keep walking to find

From Jacqui Malins, ‘If you’:

If you are reading this I may be dead or alive and you have survived past infancy

Jilly O’Brien, ‘No Laughing Matter’, which is a prime example of what Tricia Dearborn’s editorial describes as ‘science at play – revealing the world, cracking bad jokes and considering the big questions’:

Pierre met Marie in the lab He had his ion her

Jaya Savige, ‘Starstruck’:

I cannot honestly claim to have met Stephen Hawking. But once I was skidding down the steepest bridge in Cambridge – in the rain, on my rusty BMX

As well as the science poems, this Rabbit contains the winners of the 2020 Venie Holmgren Environmental Prize, with clear and accessible notes from the judges; a number of articles including one by Tricia Dearborn about her own poetry’s relation to science; a stimulating interview with Astrid Lorange; an essay adapted from a performance piece; and several reviews of recently published books of poetry. All good reading.

I have taken Rabbit 31 into the sauna with me over a couple of weeks. It was ideal reading in that contemplative environment, but alas, it’s bound with glue, and my copy is now pretty much a loose-leaf gathering of poems, images and articles. (Also I was mocked for inappropriate sauna behaviour.)

Elizabeth McMahon (editor), Southerly 80!, Vol 79 No 1 (2019)

Southerly, Journal of the English Association, Sydney, has turned 80, and though no issue has appeared since this one came out in 2019, rumours of its death were apparently exaggerated. At least, the website is back up and running.

As befits a journal of such longevity, this Southerly has something for a range of tastes: poems, stories, memoirs, critical articles, notes about literary history, and a substantial number of reviews. A handful of contributors have been around for the majority of the journal’s lifespan, while others are writers appearing in print for the first time.

In ‘A Bell Note’, David Brooks, retiring editor, offers a fascinating account of his years in the chair, including the difficulty of producing the journal with mostly unpaid labour (contributors are paid, but not editorial staff) in an environment that has become increasingly hostile to literary magazines, or at least to the notion of funding them. His account of the role of literary magazines in the funding economy is worth quoting:

The government was using the journals as a means, on the one hand, of arm’s-length funding of writers (through their payments to contributors), so that, at ground level, it did not have to involve itself in deciding which writers to fund, and, at another level, the journals’ decisions as to who was worth publishing and supporting aided the Board in its decisions concerning which writers to give individual grants to. The journals, in other words, were supported because they were a vital filter in the government’s wider program of support for Australian writing. But increasingly, in the last two decades, this ground has shifted. Literary journals continue to perform this same function, but it’s now largely for the publishing industry; to the government they are supplicants, mendicants.

Richard Nile’s ‘Desert Worlds’ is a survey of the way literature has portrayed the Australian soldiers’ sojourn in Egypt in 1916. It’s almost as if the proponents of patriotic myths should be very glad of the disaster of Gallipoli, because without it those gallant men might now be remembered as racist, sexist, drunken hoons.

Alison Hoddinott’s ‘Poetry and Musicophobia’ does a quick tour of distinguished poets and other writers who have been, not deaf like Henry Lawson, but tone deaf – unable to hold or even recognise a tune, even while being extremely sensitive to the musicality of language. There are amusing anecdotes about Hal Porter, Ezra Pound and Sylvia Plath, among others.

’Editing Daniel’ is a brief account of the life and work of Daniel Thomas, art historian and gallery director, written by Hannah Fink, co-editor of Recent Past: Writing Australian art, the first collection of Thomas’s writing.

Jumana Bayeh’s ‘Australian Literature and the Arab-Australian Migrant Novel’ glances at a couple of pages of Patrick White’s The Aunt’s Story where, she says, an Arab-Australian character appears in an Australian novel for the first time, then goes on to a fascinating discussion of two much more recent novels by Arab-Australians, Loubna Haikal’s Seducing Mr Maclean (2002) and Michael Muhammad Ahmad’s The Lebs (2018), with Edward Said’s Orientalism as theoretical backdrop.

There’s a wonderful variety of poems, including: the melancholy ‘wrap’ by joanne burns (whose apparently is reviewed by Margaret Bradstock elsewhere in the journal); the harrowing ‘Explant (caveat emptor)’ by Beth Spencer (I had to look up breast explant surgery to understand this poem); Anne Elvey’s poem in memoriam Deborah Bird Rose, ‘Grevillea Robusta’; and Jaya Savige’s ‘Coonoowrin (Crookneck)’, on which I spent far too much time and still have only deciphered less than a quarter. Just in case my reader shares my love of impossible word puzzles, here’s the opening of that last-named poem:

Hushbound, mountchain, coiled for-kin ache revenant, calm. Warm hay be stark enigma flags, but cannot rarely be sore heart to tune and luck upon your sighin'?

Decoded:

Husband, mountain, [unintelligible] [unintelligible], come. We may be [unintelligible], but can it really be so hard to turn and look upon your son?

If you can fill in the blanks, the comments section is open.

Of the reviews, Michelle Cahill made me want to read David Brooks’s The Grass Library; Toby Fitch reviewing Dave Drayton’s P(oe)Ms offered valuable insight into some contemporary poetics; Oliver Wakelin on Luke Carman’s Intimate Antipodes, perhaps inadvertently, caught me up on some literary gossip.

Jacinda Woodhead (editor), Overland 237 (Winter 2019)

As a marker of how far behind I am in my Overland reading, while I was reading this issue, the last one edited by Jacinda Woodhead, the fourth edited by her successors, Evelyn Araluen and Jonathan Dunk, has landed in my letterbox.

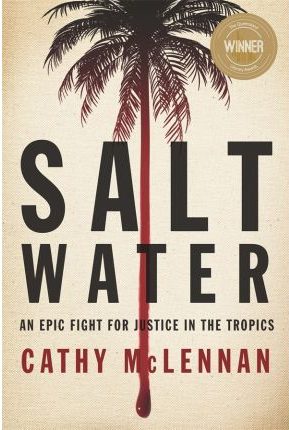

Mind you, Overland isn’t all that committed to timeliness either. The punchiest article in this issue, ‘Crocodile tears‘ by Russell Marks, is a blistering criticism of a book published in 2016, Cathy McLennan’s Saltwater. After noting that the book met critical acclaim and won awards (not to mention modified praise from bloggers such as me, link here), it goes on:

All of this should come as a surprise because Saltwater‘s myriad problems could have excluded from publication altogether.

Drawing on his own extensive experience as a lawyer working with and for First Nations people, he makes a very convincing case that Cathy McLennan’s memoir of her time as a young lawyer working for an Aboriginal legal service in Townsville is full of poor legal practice which the older McLennan seems to endorse, is misleading in many ways and feeds a racist agenda, while distracting readers from its reactionary politics by ‘vivid and shocksploitative descriptions of her clients and their lives’. (I searched online in vain for any rebuttal of the article.)

The only moment that felt seriously dated was a citation of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth in Hannah McCann’s ‘Look good, feel good‘, an otherwise excellent article about the emotional labour of beauty salon workers. Though The Beauty Myth may well hold up, it’s hard to imagine an article in Overland these days quoting someone who so bizarrely argues against masks and basic contact tracing mechanisms.

My other highlights in this issue were: ‘Only the lonely‘ by Rachael McGuirk, discusses the NSW Special Commission of Inquiry into the Drug ‘Ice’ from the perspective provided by her family’s long-term, harrowing experiences with drugs, mental illness and the justice system, ‘Inspired and multiple‘ by Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian, who describe their process of co-translating poetry as ‘a dance in chains’; ‘At the crossroads‘ by Con Karavias, a history lesson about the German revolution that raged from 1918 to 1923, but will never be restored to mainstream respectability because to do so would be to acknowledge that conservative forces unleashed Hitler and Nazism in order to crush it.

Of the four short stories, ‘Womanhood‘ by Mubanga Kalimamukwento, a Zambian coming of age story involving female genital modification, had most impact on me. ‘The Sublime Composition‘ by Gareth Sion Jenkins incorporates elements of Microsoft Word’s track changes feature in a deconstruction of an incident recorded in Thomas Mitchell’s journals of exploration, but it’s an extract from a work in progress, a taste rather than a meal.

In the eight pages of poetry, I loved the way ‘Tenor and vehicles‘ by Shastra Deo and ‘Learning‘ by Jini Maxwell resonated with each other. One begins:

Fact: things are like other things. Supposition: liking tweets is like a simile.

The other:

There is a very fine line

between writing and just sitting down

Overland has a number of regular features:

- a guest artist. Number 237 has Matt Chun, who is currently – or was in January 2020 – the Children’s Literature Fellow at the State Library of Victoria, and who brings a children’s illustrator’s sensitivity to these sometimes necessarily grim pages.

- three columnists: On failure by Alison Croggon; On the school as utopia by Giovanni Tiso; and On writing in water by Mel Campbell

- the results of at least one competition. This time it’s the 2019 Fair Australia Prize (FAP), an annual prize co-sponsored by the United Workers Union and Maurice Blackburn Lawyers. The winners – two short stories, an essay, a poem and a cartoon – share a fresh directness in the way they address issues facing working people in Australian and, in the general fiction prize winner, in India.

And three more journals are now on the shelf above my desk …