China Miéville, Un Lun Dun (Macmillan 2007)

I was quite a few pages into Un Lun Dun before I realised it’s a children’s book. It’s wonderfully fast-paced. It’s witty, endlessly inventive, full of surprising plot twists, respectful of young readers and welcoming to old ones. I had a great time from start to finish. I’d say China Miéville did too, and so would any 10 or 11 year old with the stamina for a 521 page novel and a taste for the scary fantastic.

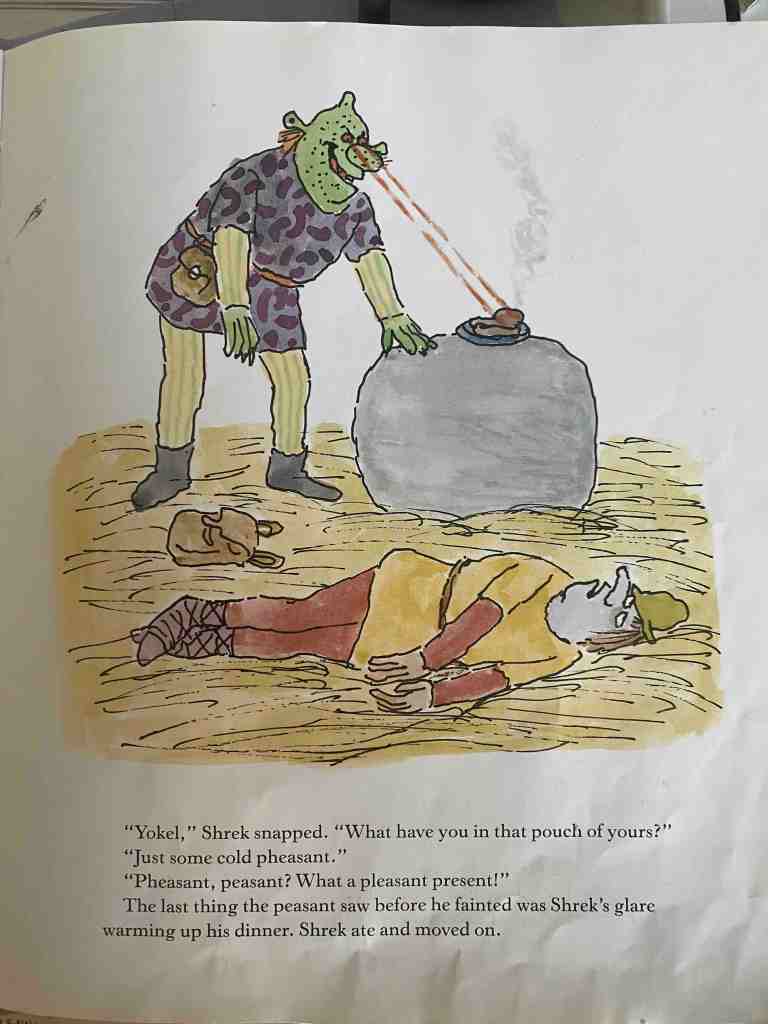

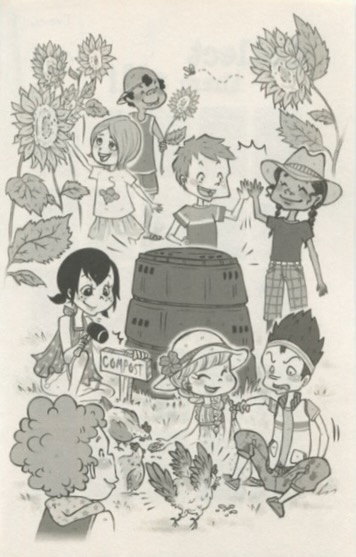

UnLondon – like Parisn’t, No York and other abcities – exists alongside its real-world equivalent. It’s mostly constructed from garbage and discarded objects that have crossed over. Broken umbrellas are particularly significant. The citizens of UnLondon are a motley lot, not all of them completely human. They are threatened by the Smog, a sentient noxious cloud that feeds on smoke and pollutants, can break up into smoglets and possess the living and the dead. Aided by its greedy or power-hungry humanish accomplices, it plans to take over UnLondon and, later, the world. There are smombies, binjas, stink-junkies, a doughnut-shaped sun and any number of weird creatures and buildings, many of them not only described but lovingly illustrated in ink drawings by the author.

Into this situation wander young Zanna and her friend Deeba. Zanna is hailed as the Shwazzy, which we learn is a phonetic representation of the French choisie. A prophetic book foretells she will defeat the Smog. But, mercifully for the enjoyability of the novel, the book is thoroughly unreliable (much to its own regret, because of course the book can talk).

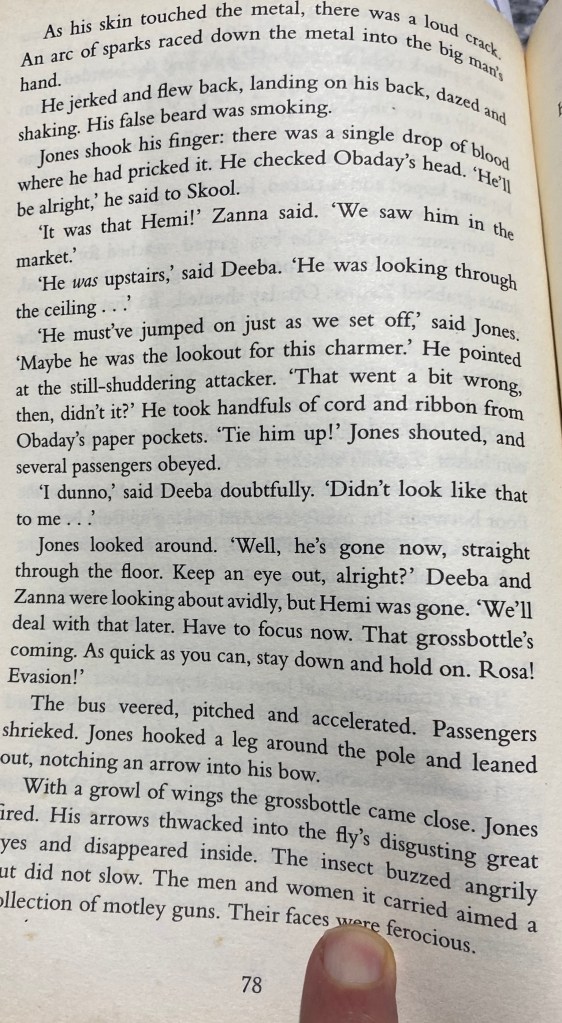

At page 78* things are just warming up, but even on this one page a gallery of characters is on display and there’s plenty of colour and movement.

Let me take you through it.

As his skin touched the metal, there was a loud crack. An arc of sparks raced down the metal into the big man’s hand.

He jerked and flew back, landing on his back, dazed and shaking. His false beard was smoking.

The skin belongs to Jones, an UnLondon bus conductor. Naturally, he also conducts electricity, and here he sends an elecric shock into the sword wielded by a big, bearded man who is attempting to abduct Zanna.

Jones shook his finger: there was a single drop of blood where he had pricked it. He checked Obaday’s head. ‘He’ll be alright,’ he said to Skool.

Jones has injured his finger by touching the tip of the bearded man’s sword. Along with Jones and a milk carton called Curdle, Obaday and Skool are Zanna and Deeba’s companions. Obaday, who wears clothes made of paper and has pins instead of hair, has been knocked unconscious on page 77. The silent Skool, Obaday’s friend and constant companion, is invisible inside a deep-sea diver’s suit. (The meaning of Skool’s name is to be revealed in the final battle scene.)

‘It was that Hemi!’ Zanna said. ‘We saw him in the market.’

‘He was upstairs,’ said Deeba. ‘He was looking through the ceiling . . .’

‘He must’ve jumped on just as we set off,’ said Jones. ‘Maybe he was the lookout for this charmer.’ He pointed at the still-shuddering attacker. ‘That went a bit wrong, then, didn’t it?’ He took handfuls of cord and ribbon from Obaday’s paper pockets. ‘Tie him up!’ Jones shouted, and several passengers obeyed.

‘I dunno,’ said Deeba doubtfully. ‘Didn’t look like that to me . . .’

Jones looked around. ‘Well, he’s gone now, straight through the floor. Keep an eye out, alright?’ Deeba and Zanna were looking about avidly, but Hemi was gone.

Hemi is a boy who approached our heroines when they first arrived in UnLondon. He seemed friendly, but they were warned that he was a ghost boy who wanted to steal their bodies. This, is turns out much later, was only partly true. But they fled from him and now they realise that he has followed them onto the flying bus, and has somehow passed down through the ceiling of the lower deck and then out through the floor. Hemi is an ambiguious figure at this stage of the story – as Deeba’s doubts about Jones’s narrative remind us.

But Hemi and the man with the sword must now wait because the bus is being attacked by a grossbottle, a giant fly, with a platform on its back carrying a gang of heavily armed airwaymen and airwaywomen.

‘We’ll deal with that later. Have to focus now. That grossbottle’s coming. As quick as you can, stay down and hold on. Rosa! Evasion!’

Rosa is the bus driver.

The bus veered, pitched and accelerated. Passengers shrieked. Jones hooked a leg around the pole and leaned out, notching an arrow into his bow.

With a growl of wings the grossbottle came close. Jones fired. His arrows thwacked into the fly’s disgusting great eyes and disappeared inside. The insect buzzed angrily but did not slow. The men and women it carried aimed a collection of motley guns. Their faces were ferocious.

And so it goes.

There is an army of unbrellas, an infestation of Black Widows in Webminster Cathedral, a shadowy organisation called the Concern that sees the Smog’s attack as a commercial opportunity, a diabolical link between the Smog and the UK government. Things are rarely what they seem. Expectations are always met but rarely in the way you expect.

What’s not to like?

I wrote this blog post on Wulgurukaba land, the luxuriant island of Yunbenun, and have finished it with the tropical sun warming my back. I acknowledge the Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.