Zheng Xiaoqiong, In the Roar of the Machine, translated by Eleanor Goodman (Giramondo 2022)

True to the promise implied in its name, the Giramondo Publishing Company invites its readers to travel widely. In the Roar of the Machine takes us into the world of migrant workers in China – that is, the mostly rural poor who have moved to large industrial centres to live and work creating what has been called an enormous floating workforce that, to quote Eleanor Goodman’s introduction, ‘comprises one of the largest human migrations in recorded history’.

Zheng Xiaoqiong, born in 1980 in Sichuan province in western China, moved when she was about twenty to an industrial city in Guangdong province on the south-east coast where she has been a factory worker ever since. Partly for her own mental health, partly to bear witness, she wrote poetry about her experiences, and soon gained a degree of fame – though in China as in most of the world, fame for a poet is a relatively modest affair. She has published a number of books of poetry and essays, and won prestigious literary prizes.

Eleanor Goodman is a poet in her own right and has translated a lot of contemporary Chinese poetry. including Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Workers Poetry (2017), which has been described as ‘a fervent testimony to the horrific, hidden histories of the 21st century’s working-class’. That description could equally apply to In the Roar of the Machines. (You can read a fascinating interview with Eleanor Goodman on the Poetry International website, at this link.)

Two things I think I know about classic Chinese poetry: it often works through a series of images, and it often deals with exile. Both those things are true of this book. In many of the poems, the alienating effect of factory work is conveyed in an accumulation of images. In these lines, chosen more or less at random, from ‘Industrial Zone’, the harsh lights of the factory are contrasted with the moonlight of the mid-autumn festival, and the phrase ‘disk of emptiness’ carries a huge weight of nostalgia for home, family, community:

The fluorescent lights are lit, the buildings are lit, the machines are lit exhaustion is lit, the blueprints are lit ... this is a night on an endless work week, this is the night of the mid-autumn festival the moon lights up a disk of emptiness

I often struggle with poems in translation from Chinese. Almost every poem in this book grabbed me and held me hard.

There are four sections, each comprising poems from one of Zheng’s books: ‘Huangmaling’ (2006), ‘Poems Scattered on Machines’ (2009), ‘Woman worker’ (2012) and ‘Rose Courtyard’ (2016). A ‘Finale’ contains a single longer poem, ‘In the Hardware Factory’.

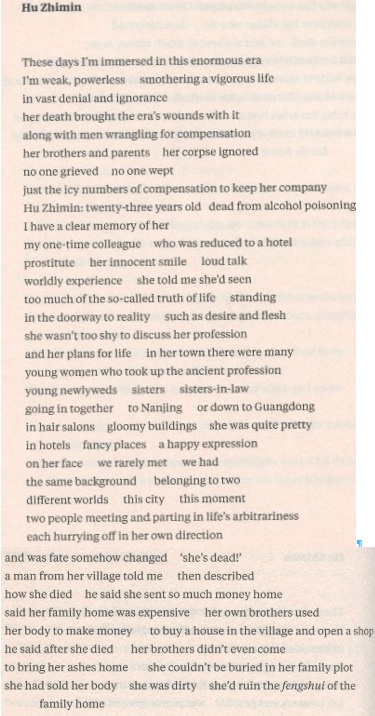

The third section, ‘Woman Worker’, is a collection of passionately feminist poems. The poem on page 76 is ‘Hu Zhimin’ (胡志敏), one of its portraits of individual women. (Right click on the image to embiggen.)

It might be worth noting that the poem becomes a lot easier to follow once you realise that, instead of conventional punctuation marks, it signals breaks in meaning or pauses for breath by longer spaces between words and by line breaks.

Hu Zhimin These days I'm immersed in this enormous era I'm weak, powerless __ smothering a vigorous life in vast denial and ignorance

This sets the tone, leading us to expect a story that will expand on what it is about the ‘enormous era’ that makes the poet weak and powerless. We’re invited to expect her ‘vast denial and ignorance’ to be contradicted in what follows.

It’s nerdy of me, but because every translation is at best an attempt (or so my high-school Latin teacher used to say), I like to compare different translations. I found Zhou Xiaojing’s version of this poem on the Poetry International website (link here). I won’t do an extended comparison of the two – except to say that I think Goodman’s generally has a better feel for what works in English – but here’s Zhou’s version of the opening lines:

These years I am immersed in an immense era feeling weak and frail allowing youthful life to be covered by gloomy negations and ignorance

I prefer Goodman’s first line and a half, as Zhou’s ‘immersed’ / ‘immense’ echo falls pretty flat. But I stumbled over Goodman’s ‘vigorous’ – how can a life be both vigorous and smothered? – and I had trouble with the literal meaning that the poet was smothering her own life. Zhou’s ‘youthful’ resolves my momentary confusion, and the poet is no longer actively stifling herself but allowing herself to be covered/smothered by external forces. Of course, ‘vast denial’ beats ‘gloomy negations’ hands down, though they do mean different things, and ‘gloomy negations’ may be more accurate.

I’m guessing that anyone who understands Chinese would know from the poem’s title that it is about a particular woman. She now makes her entrance:

her death brought the era's wounds with it along with men wrangling for compensation her brothers and parents _ her corpse ignored no one grieved _ no one wept just the icy numbers of compensation to keep her company Hu Zhimin: twenty-three years old _ dead from alcohol poisoning

That’s the skeleton of the story, arriving at last at the woman’s name. But what are these ‘icy numbers of compensation’ that displace grieving and weeping? Having raised that question, the poem holds off answering it until the final lines. For now, it continues its broad movement from the general to the specific:

I have a clear memory of her my one-time colleague _ who was reduced to a hotel prostitute _ her innocent smile _ loud talk worldly experience _ she told me she'd seen too much of the so-called truth of life _ standing in the doorway to reality _ such as desire and flesh she wasn't too shy to discuss her profession and her plans for life _ in her town there were many young women who took up the ancient profession young newlyweds _ sisters _ sisters-in-law going in together _ to Nanjing _ or down to Guangdong in hair salons _ gloomy buildings _ she was quite pretty in hotels _ fancy places _ a happy expression on her face

So much is conveyed in by piling on these images. This is personal: Hu Zhimin had worked in the factory with Zheng. We have glimpses of her at work as a sex worker: ‘innocent smile’, ‘quite pretty’, ‘a happy expression on her face’. There’s a hint of shame in ‘she was reduced’, but at the same time, Hu Zhimin didn’t try to hide what she was doing and the poem opens out to show us the ‘many young women’ have taken the same course. Their reasons for doing so aren’t named, and I suppose the poem allows the reading that these women took up sex work as an embrace of ‘desire and flesh’ or as a way of earning an income like any other, but I think it’s implied that harsh economic reality was their motivation, and there was an element of degradation in the work.

Then, back to the personal connection:

on her face _ we rarely met _ we had the same background _ belonging to two different worlds _ this city _ this moment two people meeting and parting in life's arbitrariness each hurrying off in her own direction

Both women came from small towns and migrated to ‘this city’ at ‘this moment’, but one of them left factory work for sex work, the other found a way to poetry. It’s a ‘there but for fortune’ moment.

I found the next words problematic:

and was fate somehow changed

Zhou Xiaojing’s translation came in handy for me:

not knowing what fate would bring

In Goodman’s translation, the line could be a question – did some mysterious force change their respective fates – but it’s hard to tell what’s actually being said. Zhou’s version is clearer: we are still with the two young women at the moment of parting ways, each ‘hurrying off in her own direction’ (or in Zhou, ‘each going her own way in a hurry’), and these words throw forward to the announcement at the end of the line, ‘she’s dead!’ Maybe Goodman’s opaqueness is more accurate than Zhou’s clarity, but I’m happy with the clearer version.

and was fate somehow changed _ 'she's dead!' a man from her village told me _ then described how she died _ he said she sent so much money home said her family home was expensive _ her own brothers used her body to make money _ to buy a house in the village and open a shop he said after she died _ her brothers didn't even come to bring her ashes home _ she couldn't be buried in her family plot she had sold her body _ she was dirty _ she'd ruin the fengshui of the family home

That’s the real tragedy. There’s no need to repeat that she died young of alcohol poisoning. Now we learn that her sex work was a means to create prosperity for her family back in the village. Though here it names only her brothers, we remember that the opening lines names the parents as well. They ‘used / her body to make money.’ But now that same body is treated as unclean, and left without the proper treatment of the dead.

We’re left with the image of a family home carefully ordered to be in harmony with the universe, but we know that this order has been achieved by the cruel exploitation of a family member that led to her early death. We’re thrown back to the opening line, ‘These days I’m immersed in this enormous era’. Hu Zhimin’s story sends ripples outward: the family home’s fengshui is corrupted by their callousness, the prosperity of China as a whole is built on suffering like hers, and – wider still – capitalism as a system destroys lives.

All that, and yet there’s an immediacy to the poem – we feel the pain of the poet’s loss and her indignation on her friend’s behalf.