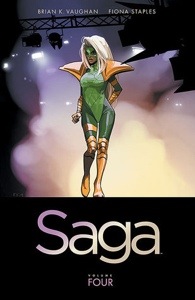

Fiona Staples and Brian K. Vaughan, Saga, Volume 12 (Image 2025)

Saga, with words by Brian K. Vaughan and images by Fiona Staples, is a space opera that has been running for nearly 15 years. Seventy-two individual comics have come out on a monthly basis, with a couple of substantial hiatuses. Volume 12 collects comics number 27 to 72.

In the middle of a forever war between a winged species and a horned one, a bi-racial child is born, and this is her story. Many forces are out to destroy the girl and her family. Hazel is her name, and she’s now 12, working in a circus and worried about the hair growing in unexpected places. Oh, and the galaxy-wide war continues.

There’s a lot going on.

I’ve blogged about the previous 11 volumes: volume 1, 2 & 3 here, 4 here, 5 here, 6 here, volume 7 here, 8 & 9 here, 10 here and 11 here. For volume 12, I’ll stick to page 78*.

Sadly, I don’t get to show you Hazel as a 12 year old, or her bad-ass mother Alana (that’s her in the cover illustration in her role of head of security for the circus), or her television-monitor headed brother. There’s no sex on this page, no violence, no cute aliens, and none of Hazel’s deliciously multivalent narrative. But you can get an idea of Fiona Staples’s visual style.

The three characters here are an obnoxious clown; Whist, the circus manager who belongs to some kind of rodent species; and Feld, a stunningly good looking circus employee.

The top two frames are a bit of silliness, a glimpse of the way the circus – a huge tent-shaped space station – is always on the edge of chaos, though the broken-down clown car is nothing compared to the land-based dolphin on earlier pages who has diarrhoea when he has to perform. The mention of the ‘strong-women’ is a set-up for an image on the very next page where two musclebound women stuff clowns into the car and push it off through the curtains into the bright lights of the circus ring. But while the reader’s attention is on this comedic dimension, grounds are being laid for a later dramatic moment featuring Whist and the clown, about which I’ll say no more.

The bottom two frames are rich with irony. Someone at the circus has been seeking a bounty from people who are hunting Hazel and her family, and Whist, we learn here, knows some skulduggery is going on. The reader has reason to believe that sweet-talking Feld is the informant, so this moment is full of tension. There are, of course, a few twists to this part of the story before the volume ends. It’s not really a spoiler to say that Hazel Alana and family manage to escape – and that the war continues.

I used to wonder where it was all leading, but now I think it might just go on forever, and continue to be engrossing fun until Hazel dies of old age as a grand matriarch in volume 90. Anyhow, it looks as if we may have entered another ‘hiatus’ and it will be some time before the next episode hits this blog.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Bidjigal and Gadigal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge their Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* That’s my age. When blogging about a book, I focus on page 78 to see what it shows about the book as a whole.

The adventures of Hazel, now at least five years old, and her two-species family continue.

The adventures of Hazel, now at least five years old, and her two-species family continue. The continuing adventures of bi-speci-al Hazel and her family.

The continuing adventures of bi-speci-al Hazel and her family.

In Volume 4, the framing story comes back to life. The characters are in exile because someone known as the Adversary had mustered a huge army and was murdering everyone in fairyland. Those who escaped set up a clandestine community known as Fable Town in New York City, with a farm upstate for those Fables (as the fairytale characters are known) who don’t look human. These two places have been hard enough to police so far, because as everyone knows, being a fairytale character is no guarantee of decent behaviour. In this issue one of the gates dividing the worlds is breached and, after centuries of believing themselves safe, the Fables face Tarantino-esque violence at an industrial level.

In Volume 4, the framing story comes back to life. The characters are in exile because someone known as the Adversary had mustered a huge army and was murdering everyone in fairyland. Those who escaped set up a clandestine community known as Fable Town in New York City, with a farm upstate for those Fables (as the fairytale characters are known) who don’t look human. These two places have been hard enough to police so far, because as everyone knows, being a fairytale character is no guarantee of decent behaviour. In this issue one of the gates dividing the worlds is breached and, after centuries of believing themselves safe, the Fables face Tarantino-esque violence at an industrial level.