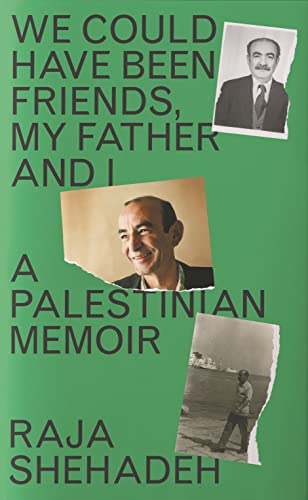

Raja Shehadeh, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir (Profile Books 2022)

When a young man at the Sydney Writers’ Festival recommended this book to me, I said, ‘What a great title!’ He didn’t miss a beat: ‘Yeah, a great dust jacket too.’ You’ve got to love the sarcastic young.

Superficial old man I may be, but the promise of the its title is what led me to this book rather than one of Raja Shehadeh’s other recent books, such as What Does Israel Fear from Palestine? (2024) or his Orwell Prize winning Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape (2008) – both with excellent titles. Since reading Annie Ernaux’s book about her father, A Man’s Place / La place (my blog post here), I’ve been hungry for more books in which the writer sets out to understand their father. This promised to be that. I was not disappointed, and I also received a masterly lesson in the history of Palestine since the nakbah in 1948.

In 1984, Raja was 33 years old and working in the legal practice of his father, Aziz Shehadeh, on the West Bank. When he saw a map that he realised was a blueprint for an Israeli occupation, he wanted to challenge Israel’s plan through the courts. His father gave advice and put his name to brief that Raja prepared, but when the PLO failed to support it he didn’t share his son’s surprise and distress. Raja asked, ‘Had he given up on using the law to resist Israel’s occupation?’

The next year, aged 73, Aziz was murdered. (The case has never been resolved. Apparently the Israeli police knew who the murderer was but didn’t want to charge him.) For maybe 20 years, filing cabinets crammed with his papers remained unopened until Raja decided to have a proper look, and found a wealth of well-ordered material which may have been the preliminary work for a memoir. This book is the narrative Raja constructed from those papers.

Aziz Shehadeh was a prominent lawyer in Jaffa, Tel Aviv, who lost everything in 1948. At first he thought he and his family would be able to return home after a couple of months when things calmed down. It was not to be.

What followed was a long, intense engagement in political debate with other Palestinians and endless attempts, some successful, to mount legal challenges to Israel’s actions. And with it all the terrible sense of betrayal by other Arab nations. As Raja said at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, he had known the broad outline of his father’s activism, but only on reading the papers did he understood his suffering.

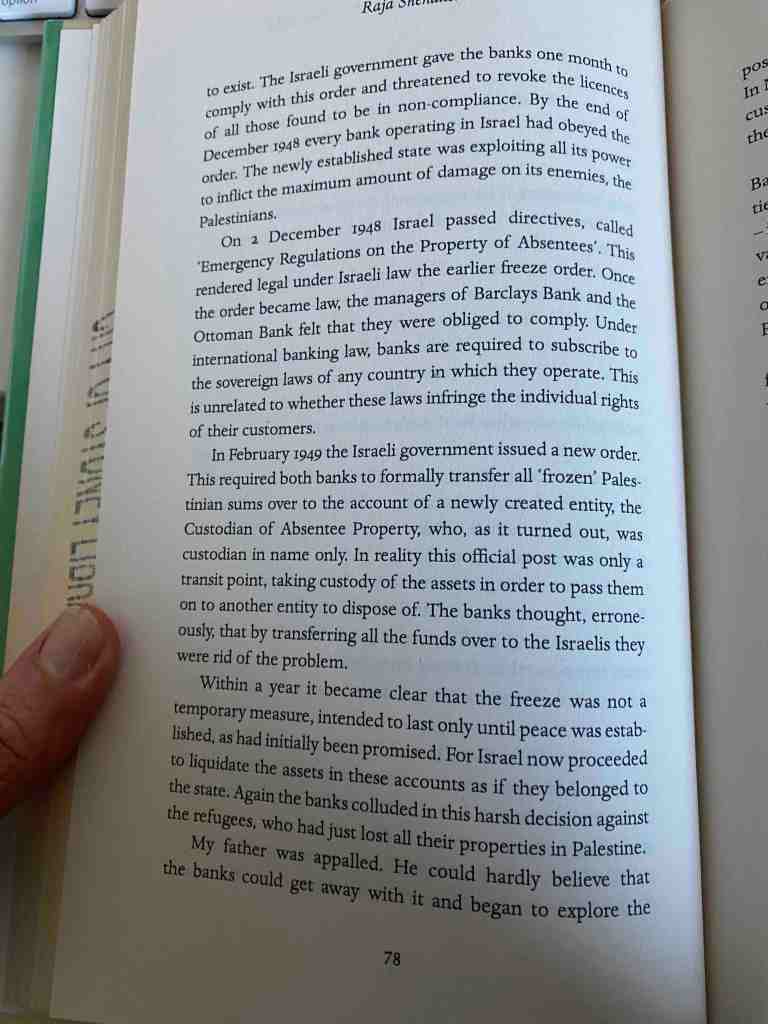

Page 78* is part of the story of one of Aziz’s great successes, what he called the ‘frozen money case’, an episode that illustrates the way Britain, Israel and the Arab states in effect combined forces against Palestinians.

When the British Mandate ended in 1948, the British Treasury declared that the Palestinian pound was no longer legal tender. This meant that for the thousands of Palestinians who had fled to other countries, any bank accounts in Palestinian currency were useless. Arab banks and the Bank of England denied all responsibility, and the fate of those accounts was left to the new state of Israel.

Israel ordered every commercial bank operating in its territory to ‘freeze the accounts of all their Arab customers and to stop all transactions on all Arab accounts’. Shehadeh points out that they refrained from calling them Palestinian accounts: ‘To them Palestine was no more and the Palestinians had ceased to exist.’

By the end of December 1948 every bank operating in Israel had obeyed the order. The newly established state was exploiting all its power to inflict the maximum amount of damage on its enemies, the Palestinians.

On this page, in measured, objective prose, Shehadeh outlines the ruthlessness of the new Israeli government. First, in December 1948, there were directives called Emergency Regulations on the Property of Absentees, with which both active banks, one British and the other Arab, felt obliged to comply. In February 1949 the Israeli government required the banks to transfer the affected funds to a new entity called the Custodian of Absentee Property. The banks could wipe their hands of the issue.

Within a year it became clear that the freeze was not a temporary measure, intended to last only until peace was established, as had initially been promised. For Israel now proceeded to liquidate the assets in these accounts as if they belonged to the state. Again the banks colluded in this harsh decision against the refugees, who had just lost all their properties in Palestine.

My father was appalled. He could hardly believe that the banks could get away with it and began to explore the possibility of a legal challenge.

The pages that follow tell of a protracted legal battle, which Aziz eventually won, alleviating the suffering of thousands of Palestinian refugees. One significant win along the way.

Aziz was at odds with the PLO. He argued that the refugees should accept that they would never be able to return to their homes. He campaigned for the notion of two states – a Palestinian state and an Israeli state – side by side. His personal story is intimately bound up with the story of the Palestinians, and it is one of many stories of sustained, systematic, heroic resistance.

Edward Said famously wrote that Palestinians have been denied permission to narrate. This book, like others by Raja Shehadeh and a score of other writers, defies that prohibition. I’ve read very little of that writing, but there are a couple of books I can recommend if you’re interested (links to my blog pasts): Drinking the Sea at Gaza (1999) by Israeli journalist Amira Hass; 19 Varieties of Gazelle (2002), a collection of poems by Palestinian-American Naomi Shihab Nye published in response to the rise of anti-Arab sentiment in the USA after September 2001; Palestine (2003) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009), groundbreaking comics journalism by USer Joe Sacco.

I wrote this blog post on land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, whose occupation since 1788 has never been legally resolved. I acknowledge the Elders past and present of this country.

* My blogging practice is focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently 78.