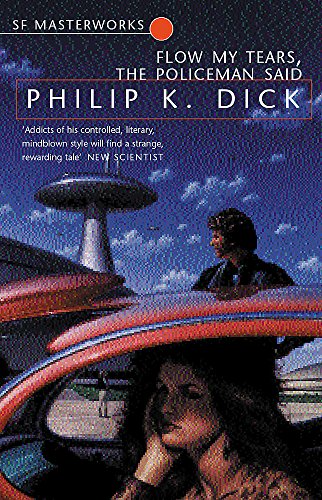

Philip K Dick, Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said (1974, Gollancz SF Masterworks edition 2001)

I have a shelf full of science fiction and fantasy books that I acquired through BookMooch after finding a list of titles recommended as essential reading in the genre. Every now and then I actually read one of those books.

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said was on that shelf.

I had previously read just one Philip K Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (my blog post here), which was the basis of the movie Blade Runner; and I’d seen at least two other brilliant movies based on his work: Total Recall and Minority Report. So I was expecting a dystopian future, a surveillance state, psychological dislocation and the kind of philosophical rumination that can be hard to tell apart from quasi-psychotic, drug-induced meandering. My expectations were filled to overflowing. The book is like a weird waking dream, put together without much care for logical coherence, and at the same time it feels somehow deeply personal. It’s also masterly story-telling.

Jason Taverner is the phenomenally successful host of a weekly TV show. He’s a six, a genetically engineered superior human, handsome, charismatic and super-smart. Without warning he finds himself in a seedy hotel room, stripped of his identity – all records of him have disappeared from the data banks, there’s no trace of his TV show, and none of his associates recognise him or have any memory of him. Somehow he has to somehow acquire forged ID papers to avoid being picked up by the pols or nats and sent to an FLC (forced labour camp).

The story progresses through a series of encounters with women: his long-term partner in the TV show who is also a six; a woman he has seduced and dumped who unleashes an alien creature on him that (we believe) precipitates his crisis; a disturbed teenaged girl who forges his documents and tries to blackmail him into having sex with her; a spectacular, drugged out dominating woman who lures him into her mansion with disastrous results; a quiet ceramicist who is impressed to be meeting a celebrity. There’s a lot of drugs, a weird death, plenty of sexual titillation (see below), and a final bonkers explanation of what has been happening that an early reviewer described as ‘a major flaw in an otherwise superb novel’, but which I loved. Take your pick.

The book was published in 1974 and set in 1988, so the book’s near future is our fairly remote past, and readers in 2023 have the extra pleasure of clocking how wrong Dick’s predictions were. People fly around the city in self-flying quibbles and flipflaps but have to find a public phone to make a call. They read the news on foldable newspapers. The 70s protest movements have led to the Second Civil War in the USA; the surviving students now live underground beneath the ruins of universities and risk being captured and sent to forced labour camps if caught outside looking for food. The USA is a police state, and everyone is apparently on drugs of one kind or another.

Also dated is a creepy sexual element that seems to function mainly to assert Dick’s status as a pulp writer. Police surprise a middle-aged man in bed with a boy who has a blank expression, and though they are disgusted by the evidence of child sexual assault it is revealed to us that the age of consent has been lowered to 13. There are regular references to pornography and phone network orgies (as close as the book comes to predicting the internet). Two of the main characters are brother and sister who live in an incestuous love-hate relationship and have a son who is away in boarding school. And so on.

While the sexy stuff might assert the book’s pulp status, there’s also a strand of references to ‘high culture’. The book’s title, as the main example, comes from the 16th century lute song ‘Flow My Tears’:

Each chapter begins with a couple of lines from the song, so that it becomes in effect a sound track, a melancholy, orderly counterpoint to the characters’ panic and disorder. Sadly I didn’t look it up until I started writing this blog post, so it didn’t work that way for me.

Taverner’s progress is marked by his encounters with women. Meanwhile he is pursued by men, chief among them Police General Felix Buckman, who listens to classical music, and whose tears flow when he decides to seal Taverner’s fate. He has one of the weirdest scenes in the book, when he stops his quibble at a refuelling station and, out of the blue, has an intimate (but not sexual) moment with a Black stranger, which Dick later said was a mystical reference to a scene from the Christian Bible (Acts 4:27–38) – which he hadn’t read.

Having said that the book seems not to care for logical coherence, I should give you an example of the writing, which is always measured, even flat. Here is the moment, about a third of the way into the book, when Buckman makes his first appearance. His personality is revealed to us deftly – his easy authority, his cultural sophistication, his kindness. At the same time, details of the book’s world are filled in effortlessly, including the presumably intentionally comic bodily reference in ‘sphincter’ and the unintentionally jarring distinction between an ‘officer’ and a ‘female officer’:

Early in the grey of evening, before the cement sidewalks bloomed with nighttime activity, Police General Felix Buckman landed his opulent official quibble on the roof of the Los Angeles Police Academy building. He sat for a time, reading page-one articles on the sole evening newspaper, then, folding the paper up carefully, he placed it on the back seat of the quibble, opened the locked door, and stepped out.

(Page 77)

No activity below him. One shift had begun to trail off; the next had not quite begun to arrive.

He liked this time: the great building, in these moments, seemed to belong to him. ‘And leaves the world to darkness and to me,’ he thought, recalling a line from Thomas Gray’s ‘Elegy’. A longcherished favourite of his, in fact from boyhood.

With his rank key he opened the building’s express descent sphincter, dropped rapidly by chute to his own level, fourteen. Where he had worked most of his adult life.

Desks without people, rows of them. Except that at the far end of the major room one officer still sat painstakingly writing a report. And, at the coffee machine, a female officer drinking from a Dixie cup.

‘Good evening,’ Buckman said to her. He did not know her, but it did not matter: she – and everyone else in the building – knew him.

‘Good evening, Mr. Buckman.’ She drew herself upright, as if at attention.

‘Be tired,’ Buckman said.

‘Pardon, sir?’

‘Go home.’