I’ve been suspicious of the notion that a poem is always a collaboration between poet and reader (or readers) – that each reader, even each reading, creates a different poem. My suspicion has been softened, but not completely dispelled, by taking part in the fabulous online Modern and Contemporary American Poetry course (‘Modpo’).

But I’ve realised that one of my favourite poems, ‘Love III’ by 17th Century English poet George Herbert, is a brilliant example of how that notion can hold up.

Here’s the poem:

Love (III)

Love bade me welcome. Yet my soul drew back

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked any thing.

A guest, I answered, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marred them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

If you’re interested, there’s a beautiful, scholarly account of the poem by Hannah Brooks-Motl at this link. What follows is not particularly scholarly. If you make it to the end you may even find it amusing.

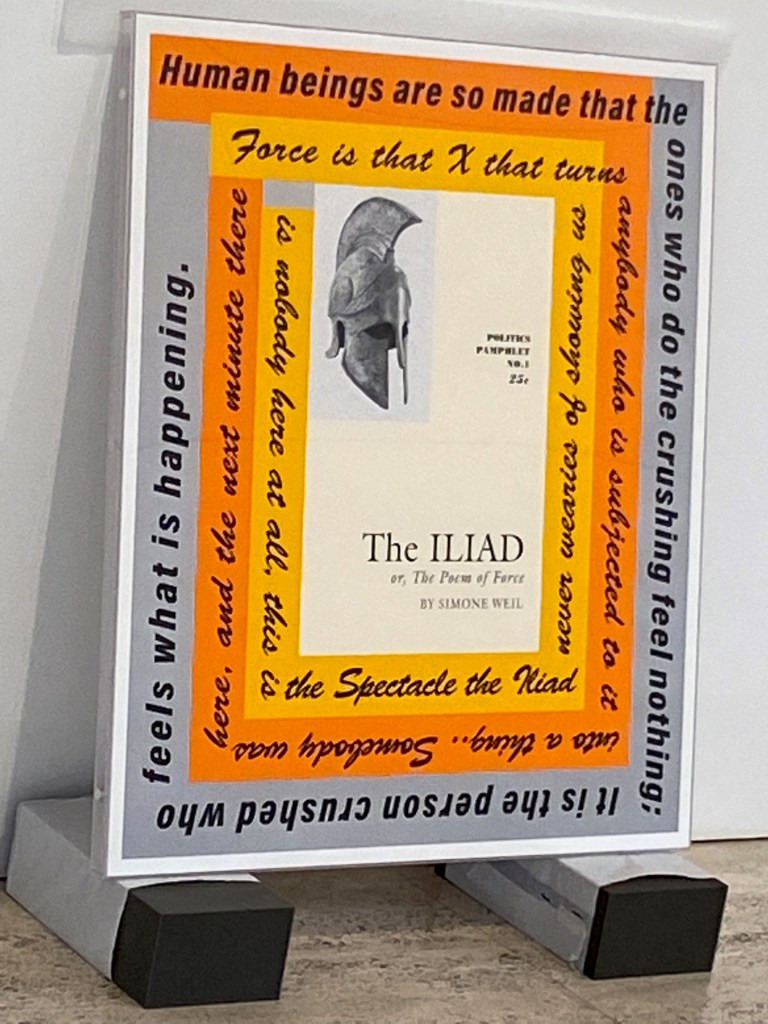

I’m currently reading Wolfram Eilenberger’s The Visionaries, translated by Shaun Whiteside, a fascinating look at a decade in the parallel lives of four brilliant women – Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Ayn Rand and Simone Weil. The book reminded me that Herbert’s poem played a major role in the life of Simone Weil.

In 1938, Weil was suffering extreme pain. She had lost her teaching job, and doctors couldn’t find a diagnosis or offer any respite. She found relief mainly in listening to sacred music, when, to quote Eilenberger, ‘the pain receded into the background and even allowed her to feel, in her deep devotion, removed from the realm of the physically restricted here and now.’ As well as the music, she turned to poetry. ‘Love (III)’ was important to her. In her Spiritual Autobiography, quoted by Hanna Brooks-Motl, she wrote:

Often, at the culminating point of a violent headache, I make myself say it over, concentrating all my attention upon it and clinging with all my soul to the tenderness it enshrines. I used to think I was merely reciting it as a beautiful poem, but without my knowing it the recitation had the virtue of a prayer. It was during one of these recitations that ... Christ himself came down and took possession of me.

It was a turning point in her life, and a wonderful example of how to read a poem. George Herbert would have been thrilled.

My reading was a little different.

I was 23 year old English Honours student at Sydney University in 1970. At the end of the previous year I had left a Catholic religious order where I had been ‘in formation’ for seven years, and at the time I’m talking of I was in my first intimate sexual relationship.

In my youthful enthusiasm, emerging from a world dominated by concepts like the love of Christ into one where I was experiencing the joys of sex and human connection as a different kind of sacred, I loved this poem for the way it eroticises the love of God.

No one else seems to have noticed that it can be read as a sexual encounter. (And I did my BA Honours thesis on Herbert, so I read a lot of critics.) It’s hard to spell out what I mean without seeming to snigger, but I don’t, and didn’t, feel at all sniggery. Love (the beloved), observes me ‘grow slack / When I first entered in’, and asks what the problem is. ‘It’s not you, it’s me,’ says the speaker of the poem. There’s a bit of back and forth, reassurance from the beloved and so on, and then she (because, heterosexual me, I was quite capable of letting ‘Lord’ be feminine) says, ‘You must sit down … and taste my meat.’ And the last line fills me with joy every time.

The poem spoke to me powerfully, and kindly, and with great tenderness about (to use cold 21st century words) performance anxiety, erectile dysfunction and alternatives to penetrative sex.

I don’t know what Simone Weil, or George Herbert for that matter, would think of that, but well, it’s my poem now.