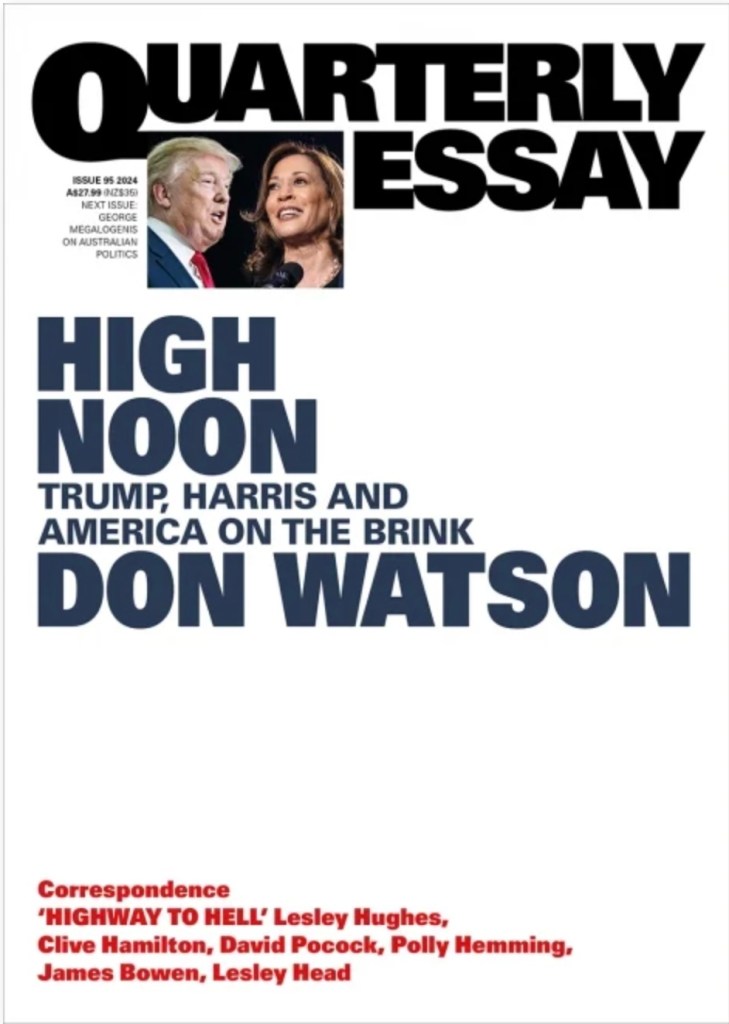

Don Watson, High Noon: Trump, Harris and America on the brink (Quarterly Essay 95, September 2024)

Eight years ago Don Watson reported on the presidential election face-off between Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton. According to my blog post, his Quarterly Essay 63, The Enemy Within: American politics in the time of Trump dwelled on Bernie Sanders as belonging to ‘a much assailed and greatly debilitated, but unbroken American tradition of democratic socialism’, and expanded his point by focusing on the history of the state of Wisconsin.

In this Quarterly Essay, as Trump is once again up against a female opponent, Watson doesn’t have a third option to discuss but he again goes local, and gives fascinating brief histories of two US cities, Detroit and Kalamazoo. These snapshots, plus his reports on conversations with Trump supporters, make the essay worth reading even though its journalistic moment is past. Maybe it’s even more readable now, because its resistance to the temptation to predict outcomes might have frustrated his readers three months ago.

The fifteen pages on Detroit are excellent: Watson traces the city’s history from the first half of the twentieth century when:

White folk from the economically depressed regions of the United States, especially Appalachia and the South; Black folk from the South and east-coast cities where wages were low and jobs hard for Blacks to get; Poles, Greeks, Irish, Italians, Germans, and people from the Middle East and the countries of Central America were all drawn to Detroit by the unstoppable car industry and the promise of five dollars a day.

In 1960 it had a population of 1.8 million. Since then ‘the city that gave the world the Ford Mustang and Stevie Wonder’ has fallen on hard times as the motor industry collapsed. Corruption, racism, predatory lending, the destruction of unions had their effects:

Detroit became a shrinking city of the poor, the poorly educated, the unemployed and the unskilled. A city of crime: corrupt in its high places, its streets plagued with violence, theft, arson, prostitution, drug dealing and addiction.

Detroit, Watson writes, ‘was the definitive American city … For a city like Detroit to fail was more than a disaster, it was a humiliation.’ Yet, his strategy of focusing on this one city, and then the contrasting city of Kalamazoo, brings home the immense diversity of the United States. It’s not a country where one story covers all.

There are insightful discussions of Trump and Harris, but you know, though I’m as mesmerised by the Trump phenomenon as anyone could be, I can’t bear to say much about that here.

The essay ends with the date: 23 August 2024. It was written after Joe Biden withdrew from the presidential race, after the Democratic Convention, but before the ‘They’re eating the dawgs’ debate.

Even the Correspondence in the following Quarterly Essay was written before the election results were known.

In the correspondence, Tom Keneally, lively as ever, contrasts Australian and US politics but doesn’t engage with Watson’s essay in any detail. David Smith, who did his PhD in Detroit, makes fascinating additions to Watson’s account of that city, including more examples of how unhinged US public life can be. Bruce Wolpe, senior fellow at the US Studies Centre, does a nice job of validating and amplifying Watson’s points. And Paul Kane, among other things former director of the Mildura Literary Festival, praises Watson for his ‘adroit outsider’s perspective’, and, in a lovely three and a half pages, manages to include references to or quotes from Raph Waldo Emerson, Alexis de Tocqueville, Robert Penn Warren (All the King;’s Men, 1946), Father Charles Coughlin (a whiff from my Catholic childhood), Woody Guthrie, Plato, John Stuart Mill, Wordsworth, and Barry Hill. He concludes with Benjamin Franklin’s reply when asked if the Constitution had established a monarchy or a republic: ‘A republic, if you can keep it.’

Both Don Watson’s essay and the responses to it are full of the pleasures of language. The subject is grim, and even grimmer when read after the event, but the telling of it is a joy to behold

I wrote this blog post on land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where we have had very heavy rain and are now sweltering in great humidity and heat. Cicadas are deafening. I acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for this land for millennia.

Perhaps a novel is just what’s needed after the news cycle has rolled on, to keep our minds and hearts alive to painful issues such as child sexual abuse in religious institutions. That, it seems to me, is the need The Crimes of the Father aims to fill.

Perhaps a novel is just what’s needed after the news cycle has rolled on, to keep our minds and hearts alive to painful issues such as child sexual abuse in religious institutions. That, it seems to me, is the need The Crimes of the Father aims to fill.