The Emerging Artist now keeps a record of the books she reads so she can easily whip up a list for the blog at this time of year. First her data:

- 62 novels, 9 non fiction, 3 art books

- 29 novels by women

- 20 novels by non English speakers

- 2 First Nations authors

Best novels

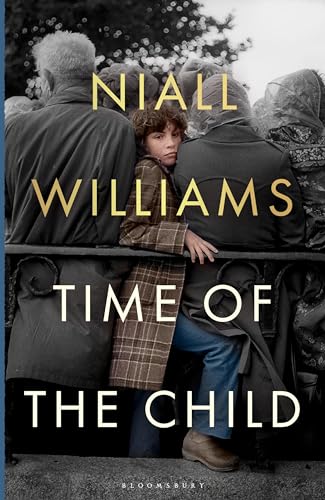

I’ve tried not just to mention books reviewed by Jonathan. That meant excluding two favourites: Time of the Child by Niall Williams and The Granddaughter by Bernhard Schlink. My best five are:

At the Breakfast Table by Defne Suman. Set in Istanbul, it weaves the story of four generations of a family, focused around one weekend, but giving glimpses into the recent history and politics of Turkiye through the lives of each character. The role of women, class and art are in the process. It was one of my random picks from the library, and I now have another of hers on order.

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon. What a terrific read, full of humour, violence, Irish sensibilities set in ancient Syracuse. The love of Euripides’ plays drives our two main characters to stage a production performed by prisoners. We saw Ferdia at the Sydney Writers’ Festival where he was equally entertaining.

Rapture by Emily Maguire. I had put off reading this but eventually, somewhat reluctantly, picked it up. It was gripping, conjuring up mediaeval Europe and a woman struggling to have independence from the constraints imposed at the time.

Brotherless Night by V. V. Ganeshanathan. Another random pick from the library, this is set in Sri Lanka as the civil war builds over a few decades. Its main character, a young female medical student, tries to sidestep the conflict as her brothers are increasingly caught up in it. A powerful read.

33 Place Brugmann by Alice Austen. During the Second World War, an apartment block in Belgium holds the range of residents that reflect the broader society – those enthusiastic about Nazism and willing to inform, those willing to put their lives in danger to hide Jews and those who become the target of hatred.

Best non fiction

What does Israel Fear from Palestine by Raja Shehadeh and Being Jewish after the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning by Peter Beinart are two excellent books about the current genocide.

From me

I can never pick a favourite or best book. Some highlights of 2024 were:

A comic: Fun Home by Alison Bechdel, an LGBTQI autobiographical work that has become a classic. A friend was shocked that I hadn’t read it already (she didn’t care that I haven’t read Pride and Prejudice).

A novel: Time of the Child by Niall Williams, one of three novels so far set in the small fictional Irish town of Faha. Its picture of the role of Catholicism in the life of the village struck a deep chord for me as a child of a Catholic family in North Queensland.

Another novel: First Name, Second Name by Steve MinOn features a Jiāngshī (a kind of Chinese vampire). This struck a personal note for me as the Jiāngshī’s journey ends at the Taoist Temple in Innisfail – and a childhood friend of mine told me that the MinOns lived down the street from him when he was a child.

A collection of essays: Queersland is full of stories about being LGBTQI+ in the state of Queensland, especially in the Jo Bjelke-Petersen era, co-edited by Rod Goodbun and my niece Edwina Shaw. I love it because it is so necessary and for obvious nepotistic reasons.

Poetry: Rather than sngle out an individual book I’ll mention the Flying Islands Poets series edited by Kit Kelen. I read 12 books in the series this year, and my life is much richer for it.

I should mention Virginia Woolf. I was inspired by a podcast about the centenary of the publication of Mrs Dalloway to plunge into that book. I’m very glad I did, though plunge is probably exactly the wrong word for my three-pages-a-day approach.

To get all nerdy, I read:

- 77 books altogether (counting journals and a couple of books in manuscript, but only some children’s books)

- 32 works of fiction

- 19 books of poetry

- 5 comics

- 11 books in translation – 4 from French (including Camus’ L’étranger, which I read in French), 2 from German, and 1 each from Chinese, Icelandic, Korean and Hungarian

- 9 books for the Book Group, whose members are all men

- 11 books for the Book Club, where I’m the only man

- counting editors and comics artists, 39 books by women and 41 by men

- 3 books by First Nations writers, and

- 14 books by other writers who don’t belong to the White global minority.

And the TBR shelf is just as crowded as it was 12 months ago.

Happy New Year to all. May 2026 turn out to be unexpectedly joyful. May we all keep our hearts open and our minds engaged, and may we all talk to peope we disagree with.

I wrote this blog post on Wadawurrung land, overlooking the Painkalac River. I acknowledge their Elders past and present and welcome any First Nations readers of the blog.