William Steig, Shrek! (©1990, Puffin 2017)

We recently watched the original Shrek movie with our grandchildren, and all four of us enjoyed it. Both our children were adults in 2001 when it was made, and grandchildren were a long way off, so I hadn’t seen the movie before, though though I’d seen clips. Nor had I been drawn into the rest of the Shrek franchise – half a dozen movies, a Broadway musical, a theme park beside the Thames. But I was aware that behind it all was a book by the great children’s author-illustrator William Steig.

When we told our six-year-old, a voracious reader, about the book she was interested, so we borrowed a copy from the library.

The six-year-old read it, said she had enjoyed it, then put it aside. I read it to the four-year-old, he said he enjoyed it, but didn’t demand an immediate reread.

I think it’s a case of the movie adaptation of a book making the book unreadable – not in the sense that it’s a difficult or unpleasant experience, but that the much broader, louder, and sentimental effects of the movie make the sly, deadpan humour and linguistic charm of the original almost impossible to discern. For example, in the movie, Shrek’s love interest starts out as a stereotypically beautiful princess, and when (spoiler alert!) she turns into an ogre she still has a degree of feminine cuteness. The love interest in the book is hideous on first encounter and remains hideous: we are never invited to see past her or Shrek’s surface ugliness to their inner beauty and goodness. Steig’s book doesn’t lose its nerve. The central joke, that the hero and then his love interest have no redeeming qualities, holds firm, and the book trusts its readers to get it. We quite like that they are pleased with themselves and each other, but we don’t have to like them at all.

That reversal of conventions and the absence of reassurance are what make the book fun.

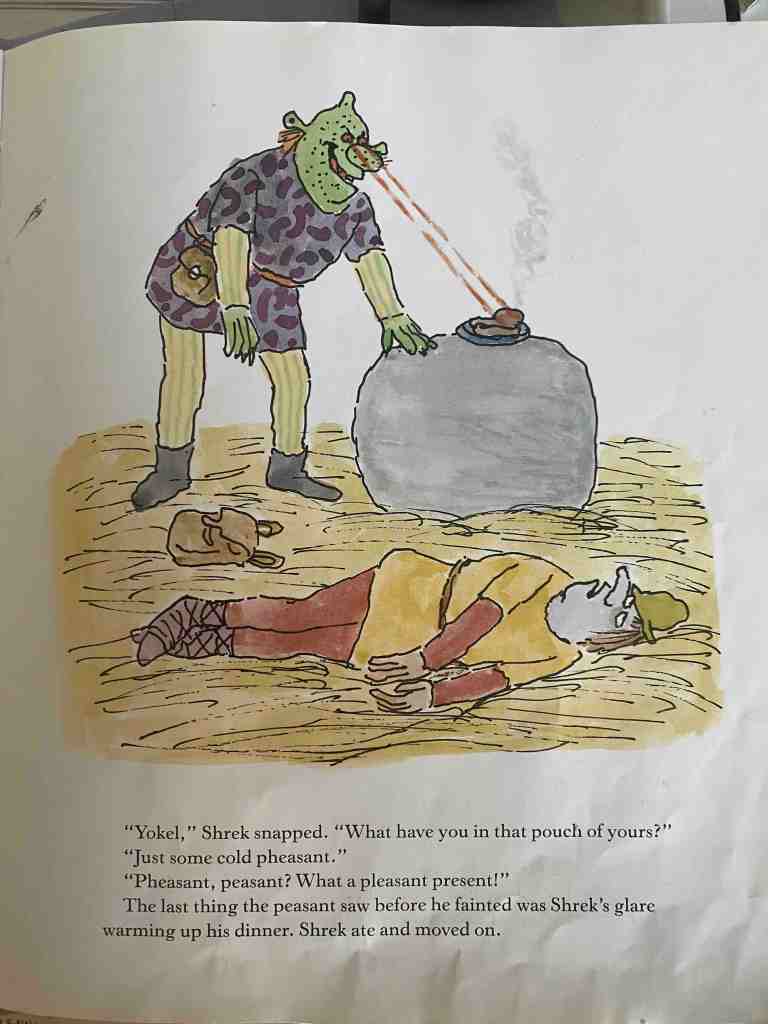

The pages of our library copy aren’t numbered, but by my count, this is page 7:

As you can see, William Steig’s Shrek has none of the movie Shrek’s gross charm. He’s just gross.

A witch has sent Shrek on a quest to find the princess he will wed. On the previous page he has encountered a peasant scything a field. The peasant has uttered a few lines of verse about his unconsidered life, and now this.

The rhyming wordplay – Pheasant, peasant … pleasant present – is typical of the joyful use of language throughout the book. The unconscious peasant, blue in the face where on the previous page he was a healthy pink, didn’t cause any evident distress in our young readers. I think they got the joke. It’s typical of Steig’s respect for young readers that he doesn’t spell out how the peasant lost consciousness. (We love Steig’s Doctor De Soto and Sylvester and the Magic Pebble for their similar tact.)

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land, over which their sovereignty has never been ceded.

* My blogging practice is generally to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77. For short books like Shrek, I am stuck with page 7.