Yao Feng, Great Wall Capriccio and Other Poems, translated by Kit Kelen, Karen Kun and Penny Fang Xia (Flying Island Books 2014)

Beijing born Yao Feng is a much awarded poet, translator, artist and prose writer. In 2014 when this small book was published he was Associate Professor in the Portuguese Department at the University of Macau, where Kit Kelen, one of the translators of this book and series editor of Flying Island Books, was also a professor.

One of the lovely things about Flying Island Books is that they have two publishers, one in the cosmopolitan city of Macao (which seems to be the accepted spelling in English) and the other in Markwell, a tiny village 16 kilometres from Bulahdelah in New South Wales. The Macao partner is ASM (the Association of Stories in Macao), which has been described as ‘the most devoted publisher of translated literature in Macao’. As far as I can tell ASM was originally Kit Kelen’s baby, and is now under the directorship of Karen Kun, another of this book’s translators.

The book’s title poem is a series of eight dramatic monologues by characters who have stood on the Great Wall over centuries, from lonely soldiers to graffiiti-ing tourists. There are other poems that deal with Chinese history, including ‘memories yet to be disarmed’, a reflection on a painting in memory of the Cultural Revolution. But not all the poems are about China – and not all of them are on serious subjects. The poet sits in the sun and watches jacaranda blooms at the summer solstice, he looks in the mirror and sees that his ears have mysteriously disappeared, he imagines in what circumstances he might renounce his atheism and ‘approach God on all fours’. Poems are set in various parts of China, but also in Portugal, the Netherlands, the USA, Japan … the list goes on. There are poems about Pushkin, Ceaușescu, Aung San Suu Kyi and Marilyn Monroe. In other words, these 130 pages contain multitudes, and are a terrific introduction to this poet.

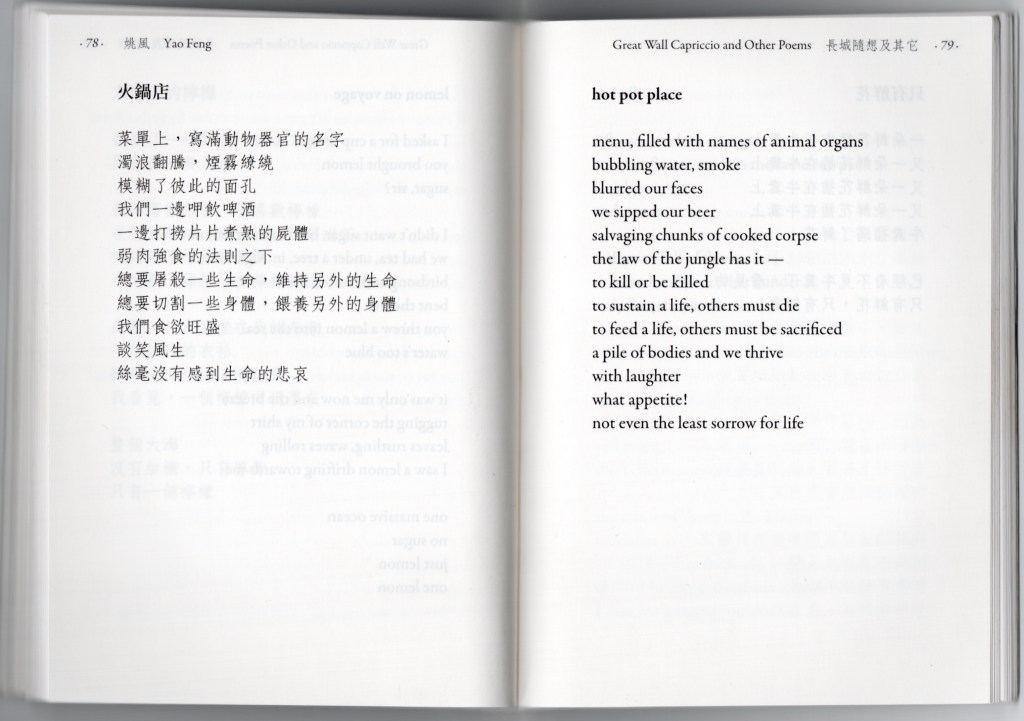

The poem on page 78, which I’m focusing on because of my arbitrary blogging rule*, has personal resonance for me.

hot pot place

menu, filled with names of animal organs

bubbling water, smoke

blurred our faces

we sipped our beer

salvaging chunks of cooked corpse

the law of the jungle has it —

to kill or be killed

to sustain a life, others must die

to feed a life, others must be sacrificed

a pile of bodies and we thrive

with laughter

what appetite!

not even the least sorrow for life

Let me start with my grandson.

My four-year-old grandson is uncompromisingly vegetarian. He likes lambs or pigs to pat in a petting zoo, not to eat. When he overheard a WhatsApp message from someone saying they’d bring a chook to the Book Group, he asked if the chook would be alive, and I felt like a criminal when I told him it would be cooked and ready to eat. There was horror in his voice when he told me one afternoon that the lunch at daycare had been spaghetti bolognese.(He went hungry that day.)

‘Hot Pot Place’ lobs neatly right there. In case you need reminding, in such restaurants a variety of uncooked food is placed on the table, and the diners drop their chosen morsels into a communal pot of boiling stock. The first four lines conjure a cheerfully exuberant social occasion in one: the smells, the sounds the tastes are effectively implied.

The tone changes in the fifth line. The diners aren’t just fishing pieces of meat from the pot, but ‘salvaging chunks of cooked corpse’. The harshness of the language is completely in tune with my grandson’s horror at bolognese sauce, and the next four lines, with their change from past to present tense, can be read as a defensive response from a meat-eater. Everywhere in nature animals eat the corpses of other animals. So it makes sense to enjoy this meal.

But this is a poem, not an argument. The lines about the law of the jungle can also be read as affirming: in eating meat we are playing our part in the natural order of things.

I remember the particular joy I had as a child – quite a bit older than four, I think – when a bullock I’d known from when he was a calf was cooked on a spit at a party to celebrate a family member’s major birthday. Terry, the bullock, even had a nickname. We children called him Pookie because his head was often adorned by a little cap of cow poo from approaching his adopted mother’s udder from behind. I don’t remember feeling any horror, more a kind of comfort that I was eating an animal I knew, not one that had been turned into a commodity.

Then the last four lines. Are they the words of someone recoiling from the carnivorous spectacle? Or are they celebrating the event? Or even somehow both?

It’s not possible to read the phrase ‘a pile of bodies’ without thinking of horrendous events of the last hundred years, including some events where the bodies have been those of animals – I’m thinking of beached whales and recent massive fish kills in New South Wales. So the line ‘a pile of bodies and we thrive’ holds an almost impossible tension. It doesn’t condemn, but it won’t look away.

The last line, I think, does make a judgement. The poem’s speaker isn’t arguing for vegetarianism. It’s ‘sorrow for life’ that is absent, not guilt. He is noticing a callousness in himself and his companions. My mind goes back to Terry/Pookie: along with the joy of eating him, there was something that you might call reverence. The poem doesn’t ask, but it opens out towards asking: is it possible to thrive with laughter and appetite and at the same time honour the lives of the beings we eat, to feel the sadness of the dispensation in which ‘to feed a life, others must be sacrificed’?

My grandson would probably read the poem differently from me. It’s a bit beyond his capacity right now, but if he ever does get to read it, I hope he finds as much joy in it as I have.

This is my sixth post for National Poetry Month, and the fourth bilingual book from the Flying Island Books.

I first read Great Wall Capriccio while flying between Djaubay land and Gadigal Wangal land. I wrote the blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present of all those Nations, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.