For years, I’ve been part of a Book Club where no one can spend more than 30 seconds talking about any book. We would eat, return books borrowed at previous meetings, each offer three books which we describe and score out of 10, then – in an order determined by a card draw – borrow up to three books each.

Over time, as most of the Club’s six members made the move to electronic books, the original idea of lending books we had enjoyed got muddied. We struggled on, meeting less frequently, two thirds of us buying books specifically so as to offer them at the Book Club.

At last we bit the bullet and agreed to try all reading the same book and discussing it. Our first title is:

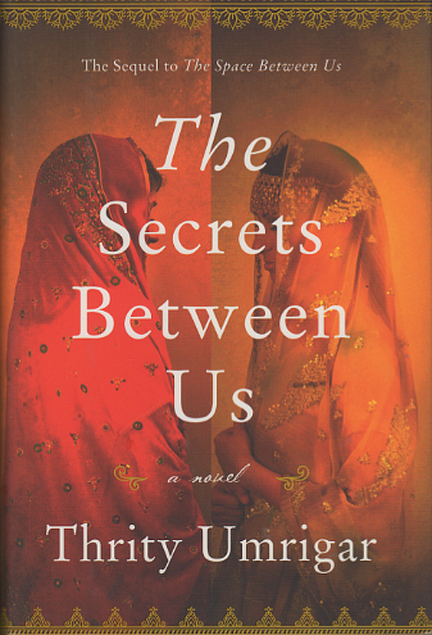

Thrity Umrigar, The Secrets Between Us (HarperCollins 2018)

Thrity Umrigar emigrated from India to the USA when she was 21 years old. Since then, among other things, she has written a number of novels in English. The Secrets Between Us revisits characters from her second novel, The Space Between Us, which was published 12 years earlier, in 2006. I’m writing this without having read more than a couple of pages of the earlier novel (I managed to get hold of a copy, but it arrived too late for the meeting). Though the second novel makes frequent reference to events from the first, I didn’t feel I was missing anything.

Before the meeting: Other demands on my time mean that this has to be brief.

It’s a terrific novel set mainly in the slums of Mumbai, featuring a brilliant gallery of women characters. It begins with Bhima, who is living with her granddaughter in a hovel in the slums. For many years she was employed in a Parsi household, virtually a member of the family, but expelled when she, correctly and necessarily, accused one of the family members of wrongdoing. She has been abandoned by her husband, and her daughter and son-in-law have died of AIDS. She makes a precarious living and enables her granddaughter to attend college by finding domestic work with a number of wealthy women.

In the course of the novel, Bhima’s life is transformed by two unlikely friendships. One is with Parvati, a woman who is even poorer than she is, who was sold into prostitution as a girl but now, as an old woman, is hideously disfigured by a growth under her chin and survives by buying and selling half a dozen shrivelled heads of cauliflower each day and sleeping on a mat outside a nephew’s apartment door, for which she pays rent. The other is with Chitra, a young Australian woman, the lover of one of Bhima’s employers, who was born in India but cheerfully disregards the rigid requirements class, caste and heteronormativity.

At the risk of reducing the book to a single paragraph, the significance of the title is spelled out in an exchange between Bhima and Pavarti. Bhima was initially shocked when she realised that Chitra and her lover aren’t just good friends, but as she comes to know them and appreciate Chitra’s generosity of spirit, she is then shocked when neighbours call them ‘a very bad name’. Here’s a quote from the conversation that happens after Bhima learns about Parvati’s background as a sexual slave, and meets her former employer who tells her how she suffers from lying about Bhima’s revelations. The lump that’s mentioned is the unsightly growth under Parvati’s chin:

‘Why do we aIl walk around like this, hiding from one another?’

(page 243)

Parvati’s thumb circles the lump in a fast motion as she ponders the question. ‘It isn’t the words we speak that make us who we are. Or even the deeds we do. It is the secrets buried in our hearts.’ She looks sharply at Bhima. ‘People think that the ocean is made up of waves and things that float on top. But they forget – the ocean is also what lies at the bottom, all the broken things stuck in the sand. That, too, is the ocean.’

The book’s story could be seen as a process of bringing those broken things to the light, and at least sometimes making them whole again.

After the meeting: We were a bit tentative about the Book Club’s new MO. We ate a pleasant dinner first, with barely a mention of the book until we moved to comfortable chairs. Conversation started out a little stiffly. Someone actually read out the questions for book groups at the back of her e-book, but we realised we absolutely didn’t want to go down that route.

The main question that got tossed around was how seriously to take the pair of books. The second book (which is the one I’ve read) has some extremely improbable benign elements, including – spoiler alert – a happy ending which may be the set-up for a third book, or not. The relative ease with which characters transcend the rigid barriers of class and custom, one person felt strongly, moves the book into the genre of fantasy, or perhaps mark it as prettified for the US mass market.

Not everyone agreed. Sure, things happen that are extremely unlikely, but they are within the realms of possibility, and the good fortune of the main characters allows the situation from which they (or at least some of them) escape to be seen more clearly by contrast. There’s no pretence, for example, that Lesbians are universally embraced by Hindu society, or that there is any kind of safety net for the poor.

Whether it’s an airport novel or a serious work of art, we all enjoyed it. All except me had read and enjoyed both books. I’m now well under way with the first one, and it’s a curious experience reading some of the harsh judgements expressed in its opening scenes, knowing that they’re based on wrong assumptions.

We agreed to carry on as a Book Discussion Club.

So this is a different group to the one you often write about? I’m impressed that you are in two reading groups/book clubs.

As you probably know, my group has been going now for 35 years, and we have almost never answered those book club question. Every once in a while I’ll have a look at them, and a couple of times I’ve found one that I thought we might like to answer, and have put them to the group with some success, but most of them feel a bit inane so I rarely even look to see if there are any questions.

I’ve not heard of these books, but reading from another culture usually offers something even where it’s not the sort of literature you usually read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s a different one. I may have mentioned it in passing, but it’s mainly been a book-swap club, or more accurately a reciprocal-book-lending club. We used to include a game of canasta on our Book Club evenings, but the impulse to actually talk about the books asserted itself over the years. Now other momentous events plus the increasing use of e-books by most of us (not me) has led us to this change.

I agree, the questions read like primary school comprehension questions. They remind me of when my lower secondary school class were taken on an outing to see Robert Speight’s play A Man for All Seasons. I was blown away by the performances as I’d seen a lot of amateur theatre in my country home-town, but very little professional: in particular there is a moment when Thomas More’s wife stands on one side of the stage saying nothing and not moving while all the action happens on the other side. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Coming home in the bus, the school principal decided to quiz me about the poem and asked a series of – your word – inane questions about the plot. I was 14, and couldn’t believe that that’s what he was interested in.

I’ve encountered these books are thanks to the Emerging Artist’s practice of choosing books at random frm the library shelves – well, almost at random, as she tends to lok for non-Anglo author names.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that’s it … like comprehension questions. BTW I love asking children about books. Some will immediately launch into the story while others will say things like, it’s about being a good friend, or telling the truth. As a teacher you probably saw that a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed about the questions. When I briefly belonged to a CAE bookgroup there were always those questions for the books we read, and they always seemed like questions devised by a Year 8 teacher of English…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly! The incident I just described in my reply to Sue was occurred when I was in the Queensland equivalent of Year 9. I imagine the average bookish Year 8 student wld also find the questions tedious.

LikeLike

I think I was lucky. By the time I was really interested in discussing books, all the students who weren’t, had left.

These days, they’re all still there, not reading the books under discussion, and making it very difficult for teachers…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These | Me fail? I fly!

Pingback: Thrity Umrigar’s Space Between Us | Me fail? I fly!