Asako Yuzuki, Butter (2018, translation by Polly Barton, 4th Estate 2024)

This was my end-of-year gift from the Book Club. It is probably an excellent book about misogyny in Japanese culture, with sharp satiric assaults on attitudes to food, with extra piquancy derived from its claim to be based on a true-crime story. It was evidently a huge success in Japanese and this English translation by Polly Barton has been reviewed enthusiastically.

The protagonist, Kira, is an ambitious young woman journalist working on a sensationalist magazine. In searching for a career-defining scoop she becomes enthralled by Manako Kajii, a woman who defies the social norms of slender femininity and is currently in prison for having killed a number of elderly men, after winning their hearts by cooking luxurious food for them. Manako introduces Kira, who until now has survived on a spartan, negligent diet, to the joy of butter – cooking with it and eating the results.

My guess is that the key to enjoying the book is to read it fast, and I’m a slow reader. The themes are real and interesting: feminism versus feminine wiles; social norms versus desire; career ambition versus enjoyment of life. But I struggled with it, and gave up soon after my obligatory 77 pages.

It may well be that Polly Barton has reproduced the feel of the original Japanese, but the best way I can describe my response to the book’s language is to say that it reads like the kind of English you find in school students’ translations. The information is all there, but in the process of capturing it, the student forgets to pay attention to the natural rhythms and sequencing of English prose. That’s fine if you’re a teacher correcting someone’s homework, but if you’re reading a novel, it keeps yanking you out of the story.

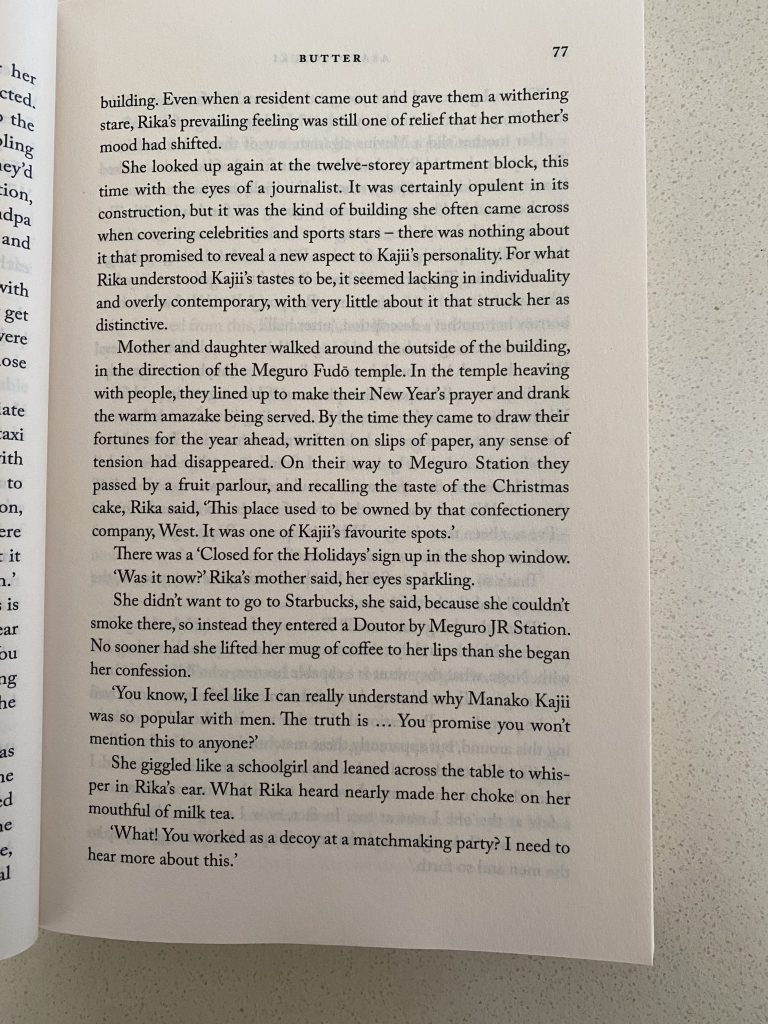

I don’t want to spoil anyone’s enjoyment, but I’ll try to articulate why I find the book such a slog. Page 77* isn’t particularly egregious, but it offers a number of examples. Rika is on an outing with her mother, partly to cheer her up, and partly with the undeclared intention of having a look at Kajii’s apartment. Rika’s mother becomes high-spirited as they inspect the building that has been ‘making a splash in the news’.

I’ll just talk about the beginning and ending of the page, but you can enlarge the image to read it in full:

The first sentence:

Even when a resident came out and gave them a withering stare, Rika’s prevailing feeling was still one of relief that her mother’s mood had shifted.

There’s nothing glaringly wrong with that, but a close look reveals a number of tiny problems contributing to the cumulative awkwardness.

To my ear, the phrase ‘even when’ suggests an extreme event of some kind, and it takes a microsecond to realise that this is something quite undramatic: a resident comes out of the building and gives the pair a withering look. For another microsecond, I wonder why the resident would pay them any attention at all. They’re just two women in a public street. And it’s not just a look, but a stare! How does Rika know that this more or less abstract person is a resident? Moving on, the awkward phrase ‘prevailing feeling’ suggests, if anything, that Rika is experiencing complex emotions, but that suggestion goes nowhere. ‘One of relief’ is clutter – why not just ‘relief’?

One last thing: the word ‘still’, which if you read this sentence without context is completely innocuous. But it’s another example of a micro-interruption to the narrative flow. This is the first time we’ve been told that Rika is feeling relieved. The reader (or at least this one) has to do a quick calculation: oh yes, Rika’s mother’s mood has lifted so of course it was implied that Rika felt relief, so now we’re being told that that relief has survived. This is a recurrent quirk: we’re told that something has happened, rather than seeing it happen.

I can enjoy a text that demands work of me, but these extra little bits of readerly labour bring no joy.

I won’t take you laboriously through the whole page, though I can’t resist mentioning the phrase, ‘In the temple heaving with people’. The meaning is clear, but it doesn’t quite feel like English.

At the end of the page, Rika and her mother are having a coffee (in a Doutor, which Rika’s mother prefers to Starbucks because Starbucks doesn’t allow smoking – in the kind of culture-specific moment that I confess to enjoying).

No sooner had she lifted her mug of coffee to her lips than she began her confession.

‘You know, I feel like I can really understand why Manako Kajii was so popular with men. The truth is … You promise you won’t mention this to anyone?’

She giggled like a schoolgirl and leaned across the table to whisper in Rika’s ear. What Rika heard nearly made her choke on her mouthful of milk tea.

‘What! You worked as a decoy at a matchmaking party? I need to hear more about this.’

Again, these are tiny things, but they accumulate. ‘No sooner than’ is just slightly wrong: can you begin to talk at the moment you lift a mug of coffee to your lips? Specifying a mouthful of tea is unnecessary and creates another of those micro-pauses: I suppose it’s technically possible to choke on a mouthful of liquid, but the term ‘mouthful’ suggests that it’s still in the mouth and more likely to cause spluttering. Having the reader learn what the mother says only when Rika repeats it is an unnecessary and (to me) annoying complication.

Your mileage may vary, and I hope it does. If you want a completely different take on the book, I recommend Theresa Smith Writes.

I wrote this blog post on land of the Gadigal and Wangal clans of the Eora Nation. I happily acknowledge their Elders past and present for caring for this land for many thousands of years.

* My blogging practice is to focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently 77.

Thanks so much for this review and the alternate perspective!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating post Jonathan. I enlarged and read the page before I read your analysis as I thought I might recognise what your criticism was as something I tend to like about contemporary Japanese writing – a sort of dispassionate flatness that conveys a lot. But I’m not sure I did find that. It does sound a bit laboured to me. The temple line in particular jumped out. I’m not sure I felt quite so picky about “even when”, however.

BTW Doutor is one of the first coffee chains we became familiar with in Japan. I enjoyed that reference too.

I’ve read some mixed responses to this book so I didn’t have it in my horizons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sue. ‘Picky’ is the word for what I’ve done here. Maybe it shouldn’t be done in public, but I’m fascinated by the task of figuring out why a piece of writing feels wrong or clunky.

LikeLike

I am too … so I enjoyed your analysis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jonathan. I was given this book as a present and I’ve been trying to decide whether to return it. You’ve decided me. Back it goes, if Gleebooks will take it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh dear, Kathy. I may have deprived you of a great pleasure. Many other people have lived this book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jonathon for articulating that frustrating feel that it reads like a school students translation…spot on for me at least. Given the current wide interest in the ‘art of translation’ I have been wondering whether this was a deliberate attempt by Polly Barton to keep the author’s actual Japanese “feel/style for want of a different word, and if so it would be interesting to hear/know whether there was a similar critique for the actual Japanese text.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! That’s exactly the problem with commenting on a translation from a language you can’t read yourself. I’m currently reading The Melancholy of Resistance by László Krasznahorkai, and am impressed by – and grateful for – the beautiful, natural fluidity of Geoge Szirtes’ translation of this weird, un-paragraphed text. I have no idea if the original text is this easy to read at the sentence level. It’s a ‘good’ translation in that it gives me a good reading experience in English. Whether it’s ‘good’ because it captures the quality of the original I have no way of knowing.

LikeLike