Emily Maguire, Rapture (Allen & Unwin 2024)

Rapture is a historical fiction set in the 9th century of the current era. An English former priest living in Germany teaches his motherless daughter to read and encourages her to think for herself. After his death, with the connivance of Randulf, a worldly a young monk who fancies her, she dresses in men’s clothing and joins the Benedictine order.

If you’ve heard almost anything about this book, you already know where the story leads. It must have received the least spoiler-careful reception of any novel. Ever.

Though I may be being over careful, you won’t get the Big Spoiler from me. I’ll just say that as one who was raised in pre–Vatican Two Catholicism, I found the subject irresistible, and the telling wonderful.

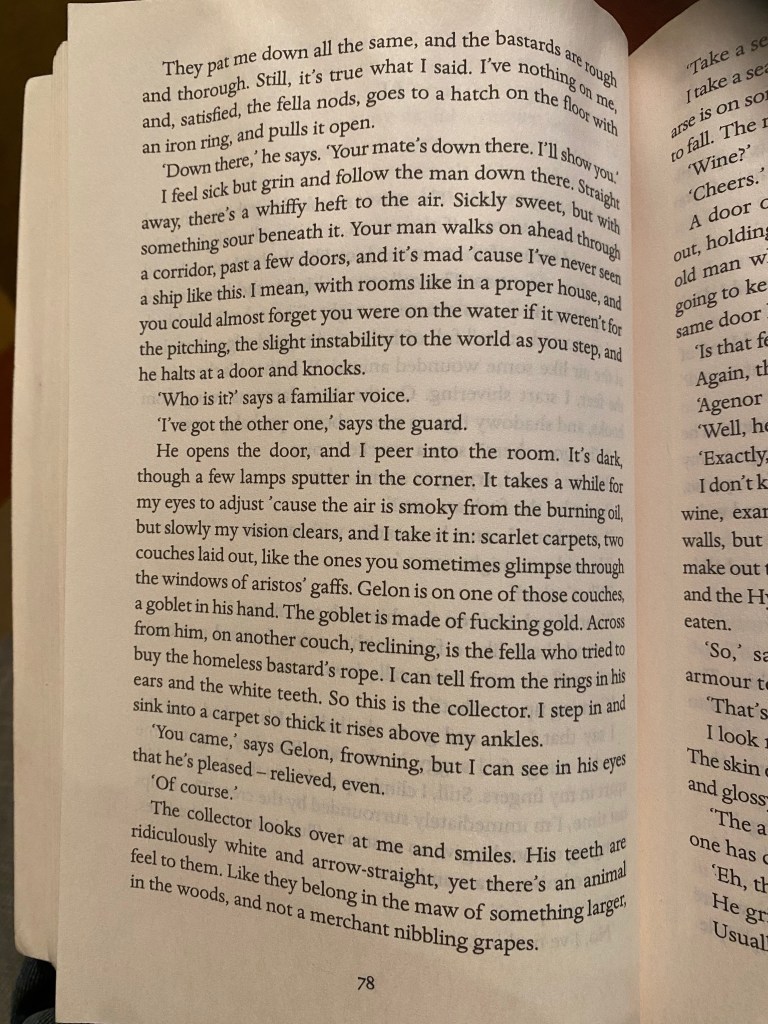

You can read excellent reviews by Heather Nielson in the Australian Book Review (link here, spoiler already in the url), Ann Skea in the Newtown Review of Books (link here), and in the blogosphere, intelligent as always, at Reading Matters, ANZ LitLovers, Theresa Smith Writes and This Reading Life. I’m keeping to my resolve and sticking with page 78*.

As it happens, possibly because of shortsightedness, it took me three attempts to land on page 78.

First I looked at page 76, where Randulf and Agnes get their story straight: Randulf has discovered a beggar-boy who was proficient in Latin and theology and will propose that he be accepted to train as a monk in his abbey. If accepted, Randulf says, there will be no trouble with the story. Among monks, he says, ‘It is not done to exchange histories or probe for intimacies.’

Realising I had the wrong page I turned, inadvertently, to page 80, where Agnes hears Randulf pissing and ‘hot panic grips her’ – but he reassures her that the monks wash rarely, sleep fully clothed, and have latrines where privacy ensures they never glimpse even an ankle of another: ‘Your modesty would not be better preserved were you empress of the realm.’

Page 78, when I finally got there, wasn’t less pointed.

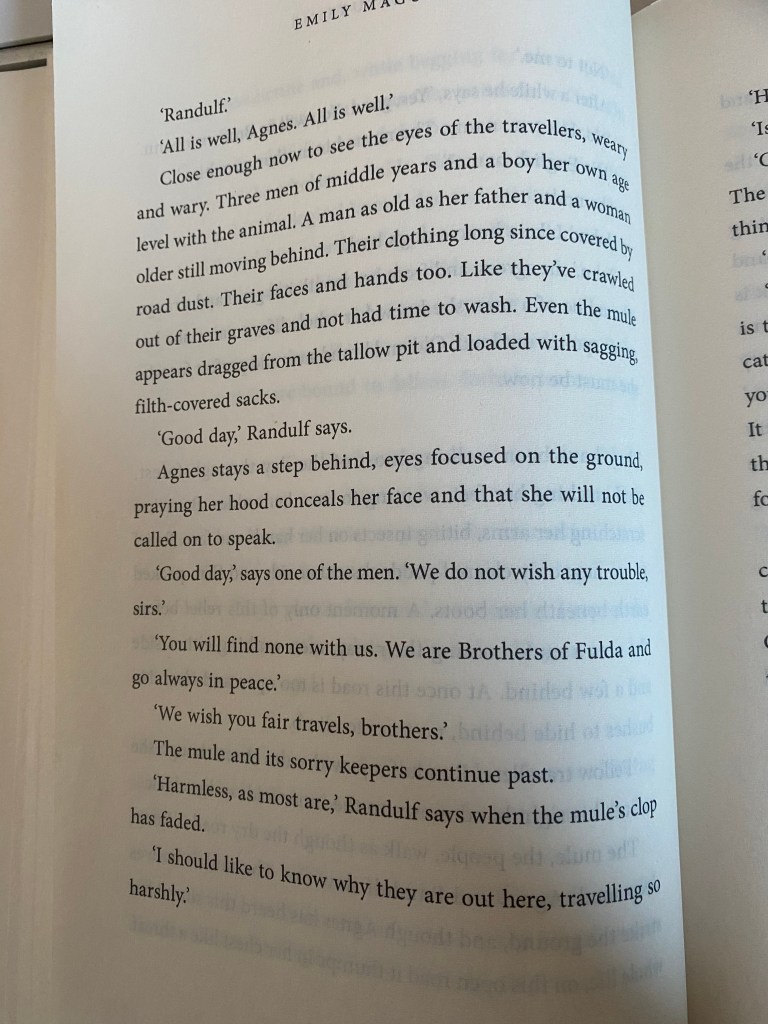

Agnes, disguised as a boy but not yet a monk, is travelling with Randulf to the Princely Abbey of Fulda (a real place, you can see a photo of the building, now a cathedral, at this link). They see some people with a mule coming their way on the open road. ‘Fellow travellers,’ Randulf says cheerfully, but his hand moves towards his concealed dagger. Agnes is terrified:

It’s an unexceptional encounter, a non-event. But it speaks to character and to the texture of the world Emily Maguire has created, and it foreshadows later events.

‘Randulf.’

‘All is well, Agnes. All is well.’

The relationship between these two characters is one of the joys of the book. Agnes is still a teenager. Randulf is older, but still a young man. He has won her trust and confidence by his genuine appreciation of her as a thinking person when he came to visit her father. They have had one sexual encounter – not exactly rape, but not a good experience for her, and in her piety and her abhorrence of childbirth she has made it clear that it is never to happen again. (Spoiler: it does, only better!) These two lines of dialogue evoke their current relationship: she looks to him for protection; as a man of he world he can reassure her.

Close enough now to see the eyes of the travellers, weary and wary. Three men of middle years and a boy her own age level with the animal. A man as old as her father and a woman older still moving behind. Their clothing long since covered by road dust. Their faces and hands too. Like they’ve crawled out of their graves and not had time to wash. Even the mule appears dragged from the tallow pit and loaded with sagging, filth-covered sacks.

There’s a Candide element to Agnes’ story. She has had a protected life, and is about to enter a differently protected life in the monastery. This is her first glimpse of the hardship endured by people who do not enjoy the protection of the Church or a prince. On the next page Randulf explains that it is not lack of godliness that makes life hard for people from further north, but economics – the further from big churches people live the greater their poverty, as they share less in the wealth accumulated by the Church.

‘Good day,’ Randulf says.

Agnes stays a step behind, eyes focused on the ground, praying her hood conceals her face and that she will not be called on to speak.

‘Good day,’ says one of the men. ‘We do not wish any trouble, sirs.’

‘You will find none with us. We are Brothers of Fulda and go always in peace.’

‘We wish you fair travels, brothers.’

This is wonderful use of dialogue to evoke the dangers of that world. We also see that at this stage Agnes is not confident in her disguise. With the passage of time, though she identifies completely as female (this is not a novel about gender fluidity) she becomes more confident that her disguise will work (until, not a spoiler, it doesn’t!).

‘Harmless, as most are,’ Randulf says when the mule’s clop has faded.

This is an adept piece of foreshadowing. The pair are to go on another journey years later when Agnes is fully Brother John. Again Randulf will be protective, but plague and war have made the environment infinitely more dangerous and hostile. The horror-movie quality to some of the description on page 78 – ‘crawled out of their graves’ and ‘dragged from the tallow pit’ – prepares the reader at a subliminal level for a pivotal moment on that later journey where Randulf and Agnes are horrified by a spectacle that is described only in a couple of disjointed phrases many pages later, but which the reader pretty much has to imagine.

That’s just one page: sadly it doesn’t contain any of the steamy sex, or the equally enthralling theological argumentation. It conveys only a little of the constant dread that hangs over Agnes/John, which for me is the most powerful element of the book. She is doomed, but not before some magnificent achievements and for me the way she meets her doom is both devastating and narratively satisfying.

I wrote this blog post on land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where a kookaburra flew right in front of me as I was walking this morning. I acknowledge the Elders past and present of this beautiful country, never ceded.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.