Susan Choi, Flashlight (Jonathan Cape 2025)

Be warned: the back cover blurb of this novel reveals something that the novel itself only begins to hint at at about the midpoint. Luckily I didn’t read the blurb until after I’d reached that hint – but thanks a lot, Jonathan Cape!

Before the meeting: I’ll avoid spoilers here, and just say the novel becomes something quite different from what you might expect from the first hundred pages or so. But when you go back and reread the start, you find that the writer has played fair. Sharper and better-informed minds than mine may well have understood the broad shape of the story from the beginning.

As in many novels these days, each chapter takes up the story from the point of view of a different character.

There’s Louisa, whom we first meet as an intelligent, uncooperative child in a therapy session: she has lost her father, presumed drowned, a loss that hangs over the whole book.

Seok, Louisa’s father, was born in Japan just before World War 2 to Korean parents. When the war ends he is shocked to discover that he isn’t in fact Japanese. His parents emigrate to North Korea, but he refuses to join them and goes instead to the USA where, now known as Serk, he gets a job at a provincial college, marries, has a daughter (Louisa) and lives as much of the American dream as is allowed to a Korean green card holder in the 1960s and 1970s.

Serk’s white wife, Anne, escapes from the thrall of a charismatic religious leader, garners an education by doing secretarial work for a literary scholar, and marries Serk. She’s dramatically unhappy in the marriage, especially when she accompanies him on a temporary posting in Japan. By the time of his disappearance at the beach, she is almost completely disabled by alienation from Japanese society and what turns out to be multiple sclerosis.

As well as those three main characters, there’s Tobias, Anne’s child by the charismatic religious leader, whom she gave up to be adopted at birth. He comes back into her life as a troubled teenager and continues to play a role over the decades. And one other character, a South Korean named Ji-hoon, has a chapter to himself late in the book.

So it’s a family story, and the family is fractious. Mother and daughter don’t have a single conversation over the decades that remains affectionate or even cordial for more than a minute. Before he disappears, Seok/Serk is abrasive both to his family and to pretty much anyone who tries to get close to him, especially other Koreans. Tobias is charming and kind, but loopy. And, the miracle of it, we like and care about them all as one small family being crushed under the weight of geopolitics.

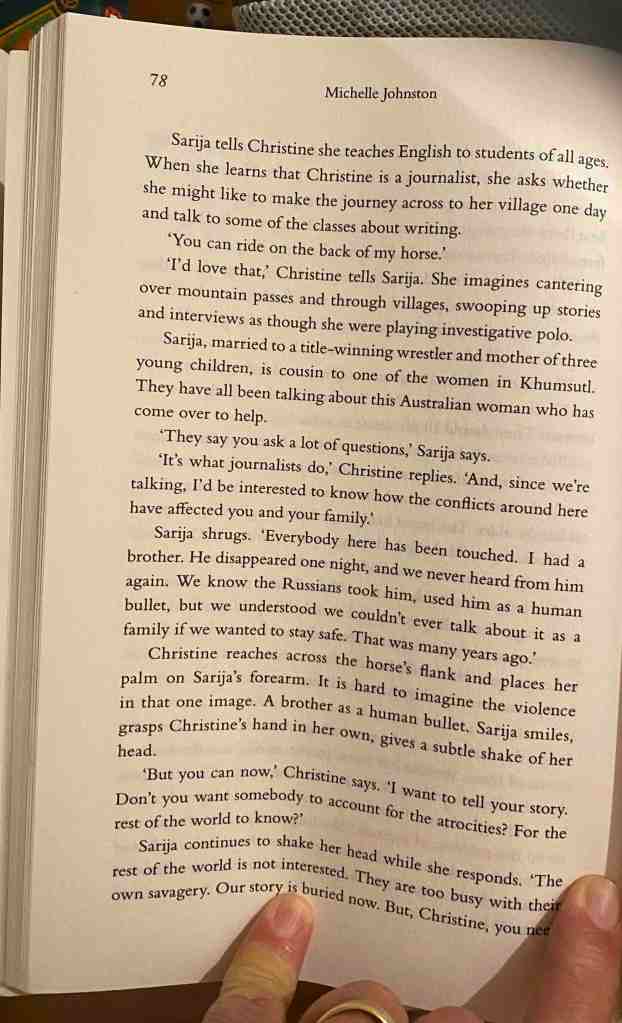

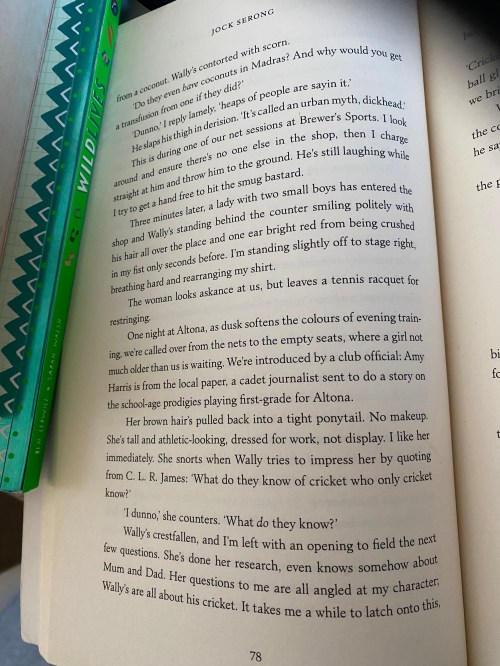

Page 78* is in one of Serk’s chapters.

A lot is happening on this page. Serk meditates on his connection with his daughter, on her brilliance and creativity. He briefly acknowledges to himself that his bursts of rage are beyond his control.

Only five and six years old when she’d created these things; her mind was always at work, it amazed him. He was trying to make her a present as well, and nights he didn’t feel compelled to leave the house, blown on a gust that he couldn’t control, he worked on the gift in their basement, and entered a rare sort of peace from using only his hands, not his mind.

And he tackles correspondence with his sister Soonja, the only family member who has stayed in Japan. In a typically tangential way the narrative acknowledges the racism in the background of the action that happens in the USA (there is racism in Japan too, similarly backgrounded for the most part).

He had a letter in progress that he extracted, as well as the series of received letters. It bothered him that their glaringly foreign airmail sheets, outweighed by their numerous conspicuous stamps, arrived so often at his office, despite such exoticism being, as he knew, almost expected of him, as the only foreigner on the permanent teaching staff. That he was using his college letterhead and not an airmail sheet himself was pure vanity for which he’d pay with the stamps.

Then we are shown a little of the content of the correspondence. Here, late at night and alone, he is able to engage with his Korean life, of which his US family and colleagues are completely unaware.

Running his eyes over his characters, he read, where he’d left off, ‘I cannot even begin to consider this without having confirmation in hand,’ and then he had to go back to the most recent letter to refamiliarise himself with Soonja’s latest equivocation. Or perhaps it was confusion, or ill-founded conviction, or just a function of her wretched written Japanese, arrested at the level of a child; she’d never had a scientific mind in the first place, her emotionalism often caused her to misrepresent supposition as fact, and being obliged to write him in her poor Japanese because his written Korean was undeniably worse likely added resentment to the other counterfactual tendencies in her personality; they might have last seen each other almost twenty years before, but he was still her elder brother. He still remembered all her shortcomings.

‘The permits are certain, the time is not certain, it cannot be made certain until you because for just a short length so you are the problem as I said in my letter before. Should I tell our parents you say NO?’

If that doesn’t make sense to you out of context, be reassured. It’s close to incomprehensible when you do have the full context. Later, Serk meets up with Soonja in person, but we never get a clear idea of what she is asking of him. What we know is that Seok, now Serk, feels a tremendous gravitational pull of eldest-son responsibility for his family, and that he resists this pull. We can’t tell what it is that they want from him. Around about this page, I started to wonder if he didn’t drown a year or so after this scene, but somehow deserted his beloved Louisa to go to North Korea. (That’s not a spoiler, I’m not saying if I was right, just that there’s a growing sense of unease about what happened.)

After the meeting: We all enjoyed this novel. Its acknowledgements list fifteen books about Koreans in Japan and the historical events that impinge on Serk and his families. Some of us had never heard of these events (I’m in that group). Others knew of them, and so weren’t completely surprised by the revelation that arrives soon after the halfway mark. One person thought they were urban myths but she was reassured when we looked up Wikipedia.

The discussion brought to light a feature of the book that I hadn’t focused on: many narrative strands are simply not resolved. For instance, there is one other Asian staff member at Serk’s college, known as Tom. He is also Korean, though Serk does his best to keep him at arm’s length and at one stage has a blazing row with him when he believes, wrongly, that he is a North Korean sympathiser. Tom disappears and soon after so does his distraught wife. We never learn what happened to them. For another instance, Louisa as a young adult marries a young man she meets on a bus – he is unwashed and smelly, and we understand that she finds this comforting because in that way he is similar to her older half-brother Tobias who was kind to her after Serk’s disappearance. She marries him, and then he pretty much disappears from the story except as an offstage character – wealthy, entitled and abusive (though we don’t learn any details). Another: when she’s old and living as a grumpy isolate in a community of old people, Anne develops a relationship with a man named Walter. The beginnings of this connection are beautifully realised as Walter is cheerfully unfazed by Anne’s prickliness. But then, as years pass with the turn of a page, he’s not there any more. As someone pointed out, given that the book’s central event is a disappearance, it’s only right that there are many subsidiary vanishings.

Perhaps related to that, one person felt that the shift of narrative focus with each new chapter was frustrating. Balls were left in the air and by the time we came back to that person the balls had landed and the person’s life had moved on. I certainly felt a kind of whiplash, especially in the final third, when time passes quickly, but I wasn’t frustrated so much as energised.

We discussed this book along with Michelle Johnston’s The Revisionists. Both books deal with significant historical events of the past half century. Reading The Revisionists I felt like a FIFO western observer. Flashlight is more like a deeply intimate conversation.

The group met on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where I have also written this blog post. I was born on MaMu land, and spent formative years on the Gundungurra and D’harawal land. I acknowledge Elders past and present of all those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.