Rebecca F. Kuang, Yellowface (The Borough Press 2023)

Before the meeting: It’s a thing: books – and movies – that deal with questions of authorship. The protagonist of Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World (2014) presents a young male artist as the creator of her sculptures. In Cord Jefferson’s movie American Fiction (2023, based on Percival Everett’s Erasure (2001), which I haven’t read), an African-American novelist writes a trashy novel full of the stereotypes he despises, and presents its author as a fugitive from justice. I won’t do a spoiler on Björn Runge’s movie The Wife (2017, based on a 2003 novel by Meg Wolitzer). In Caledonian Road, Campbell Flynn knocks off a self-help book for men and has a photogenic young actor pose as the author. And that’s just some relatively recent ones that come to mind.

Yellowface is an entertaining addition to that list.

June Hayward, a young white woman whose first novel has done poorly, has an uneasy friendship with Chinese-American Athena Liu, a fabulously successful one-book novelist. When Athena dies suddenly with June as the only witness, June gets hold of her unfinished manuscript, which deals with aspects of Chinese immigrant life in North America. She sets about editing the manuscript and completing the story, telling herself that she is doing it to honour Athena. She gradually comes to think of the novel as primarily her own work and sends it to her agent over her name.

The novel is a publishing sensation and, without actually claiming Chinese heritage, June allows herself to be seen as Chinese. Her Hippie parents had given her ‘Song’ as a middle name, so – she rationalises – it’s not actually lying when she adopts the Chinese-sounding pen name of June Song and lets people make their own assumptions. Anyhow, Athena’s research consisted of extracting stories from other people, so they were already stolen property. And other rationalisations.

Needless to say, things go very wrong. Right up until the last movement I was having a great time. There’s a marvellous scene where June is invited to do a reading to a local Chinese community, where her hosts – including one elderly man whose experiences are similar to those narrated in the novel – are genuinely shocked when they realise she is not Chinese, but remain icily courteous. Social media users are infinitely less restrained.

We see it all from June’s point of view. We sorta-kinda believe the stories she tells herself, and even when she crosses the line into outright deception, we sympathise – until we don’t. June may acknowledge that she hasn’t been completely honest, but she continues to see herself as the victim of unfair attacks until the end of the book. But somewhere along the line, and I imagine the precise point differs from reader to reader, she loses our allegiance. So at the end, where she comes up with a way to redeem herself in the eyes of the publishing and reading world, we are led to believe that it will probably work, but are disgusted by a world where that is the case.

It’s cleverly done. The introduction of some unconvincing horror tropes spoiled the big climax, but I can forgive that.

Page 77* is a nice example of one of the strengths of the book. If you’re going to write a satire of identity politics in the publishing industry, you’d better make your version of the industry seem real. Kuang does that. June’s conversations with her agent and editor, her meeting with the marketing executives, the closing of ranks among authors, followed by the shunning once the scandal becomes too much: all feel real. The description of publication day on page 77 is surely taken from life:

Months become weeks become days, and then the book is out.

Last time, I learned the hard way that for most writers, the day your book goes on sale is a day of abject disappointment. The week beforehand feels like it should be the countdown to something grand, that there will be fanfare and immediate critical acclaim, that your book will skyrocket to the top of all the sales rankings and stay there. But in truth, it’s all a massive letdown. It’s fun to walk into bookstores and see your name on the shelves, that’s true (unless you’re not a major front-list release, and your book is buried in between other titles without so much as a face out, or even worse, not even carried by most stores). But other than that, there’s no immediate feedback. The people who bought the book haven’t had time to finish reading it yet. Most sales happen in preorders, so there’s no real movement on Amazon or Goodreads or any of the other sites you’ve been checking like a maniac the whole month prior.

According to Wikipedia, Rebecca F. Kuang’s first novel, The Poppy War, was a big success, but I am pretty confident that its 22-year-old author had exactly such a ‘day of abject disappointment’.

After the meeting: As usual, our meeting was convivial, and people had a range of responses. I was a bit of an outlier in feeling generally positive about the book, but I wasn’t the only one to derive at least mild enjoyment from the meta stuff: the Asian woman writing in the first person as a white woman pretending to be Asian. Someone wondered out loud how James would have been received if the author was revealed to be white, Helen Demidenko/Darville/Dale and The Hand the Signed the Paper was mentioned. But I don’t think anyone else just enjoyed Yellowface as a light satirical tale.

At least one other chap couldn’t for the life of him see what there was to enjoy. From memory, he was something like, ‘Yes, I get what you’re saying about identity politics and the publishing industry, and maybe even that there’s satire happening, but it’s not funny, there are no real characters, and nothing interesting happens. June, the protagonist, doesn’t develop and we don’t learn anything about her beyond the superficial.’

There were a number of positions in between. The extreme implausibility of the big climactic scene was something we could all agree on. Someone said that the effect staged there would have taken the resources of a Taylor Swift concert to pull off. I couldn’t disagree.

But we had an excellent time together, enjoyed the food and the fleeting visit from a teenager who lives in the flat, shared stories (including some tales of school reunions, of which the outstanding one was the 40th reunion of a former Australian Prime Minister who had been bullied at school and continued to be bullied 40 years later), laughed a lot, had peanut-flavoured ice cream, and didn’t feel at all competitive with (something I found out about recently) the all-male Book Group that has been meeting for 25 years in Melbourne.

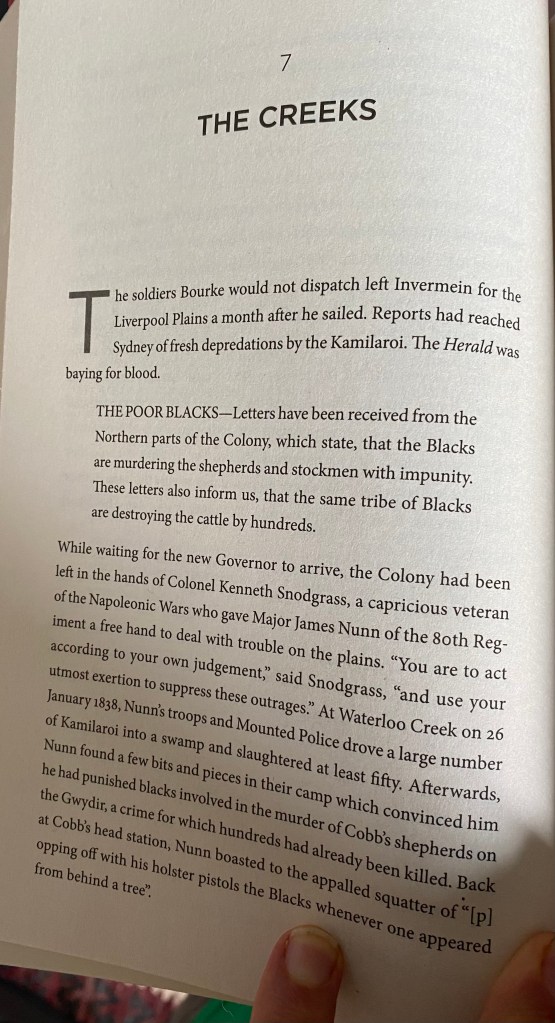

I pressed ‘Publish’ for this blog post on Gundungurra land, where the creeks are flowing and the air grows cold as soon as the sun goes down. I read the book on Gadigal Wangal land, and brooded on it in Yidinji country and the many lands I have flown over or driven through in the meantime. I acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for these lands for millennia, and continue to do so.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page of a book or journal that coincides with my age, which currently is 77.