It’s been a while since I’ve blogged about my grandchildren’s reading. Both do quite a lot.

I’ll write about the four-year-old another time. For now, I’ll just say that he loves Tabby McTat by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, which I blogged about four years ago, when his big sister was also enamoured of it.

Our newly-turned-seven-year-old has become a comics reader. Unlike the Donald Ducks and Phantoms of my childhood, her comics are little books, and seem to be mainly adapted from series of non-graphic novels. Partly as dutiful grandfather and partly (mostly?) as committed reader of comics, I’ve read two books from her current obsessions. (I did dip into a Babysitters’ Club title, but couldn’t make myself read the whole thing.)

Dav Pilkey, Dog Man: For Whom the Ball Rolls (Graphix 2019)

I’d heard of Dav Pilkey’s Captain Underpants, but had no idea until I looked him up on Wikipedia that he had received the prestigious Caldecott Honor Award (in 1997, for The Paperboy) or that he had been named Comics Industry Person of the Year in 2019. His first name, I also learned there, doesn’t come from a non-Anglo heritage but from a misspelled name tag at a fast food outlet.

This is the seventh of the Dog Man books. It’s good fun.

The first pages explain that the hero has had a head transplant. His new head came from a dog, and now as he continues with his work as a police officer, his doggy abilities and instincts often come in handy. Sadly, and hilariously, they also cause problems.

In this book, whenever Dog Man comes close to making an arrest, the bad guy throws a ball and he is compelled to chase after it.

Having written that much, I realise that I didn’t actually finish reading the book. In an increasinglty rare treat for both of us, I read it to my granddaughter until life made other demands. I enjoyed what I did read, and will try to sneak a further look if I can find it among the chaos of books in their bedroom.

Tui T. Sutherland, Barry Deutsch, Mike Holmes & Maarta Laiho, Wings of Fire: The Dragonet Prophecy, the graphic novel (Graphix, an imprint of Scholastic, 2018)

Tui T. Sutherland’s Wings of Fire series is a major phenomenon in YA fantasy. The first (non-graphic) novel, The Dragonet Prophecy, was published in 2012, and has been followed by fourteen more, plus two stand-alones, a number of novellas (‘Winglets’), and other spin-offs. The series is currently being adapted into ‘graphic novels’ (I prefer to call them comics) by Barry Deutsch, with art by Mike Holmes and colour by Maarta Laiho. Evidently the sequential art version makes the stories accessible to a younger readership, as my granddaughter has devoured the first six volumes. I have just read the first.

In the world of this novel, intelligent dragons are the dominant species. There are at last six dragon nations / subspecies, each with its own powers. A war has been raging for twenty years – a war of succession, sparked by the death of a queen at the hands of a Scavenger (a creature we recognise as human). There is a prophecy that five dragons ‘who hatch at brightest night’ will end the war and bring about peace.

The story begins with the hatching of those five baby dragons (‘dragonets’). They spend their early years imprisoned in a cave, protected from the outside violence and trained for their future task by formidable adult dragons, the Talons of Peace, who don’t much like them. They bicker like siblings, study the history of the war, and test their diverse powers. Like many institutionalised children, they form powerful bonds of affection and are fiercely loyal to each other. As you’d expect, they escape from the cave and adventures ensue.

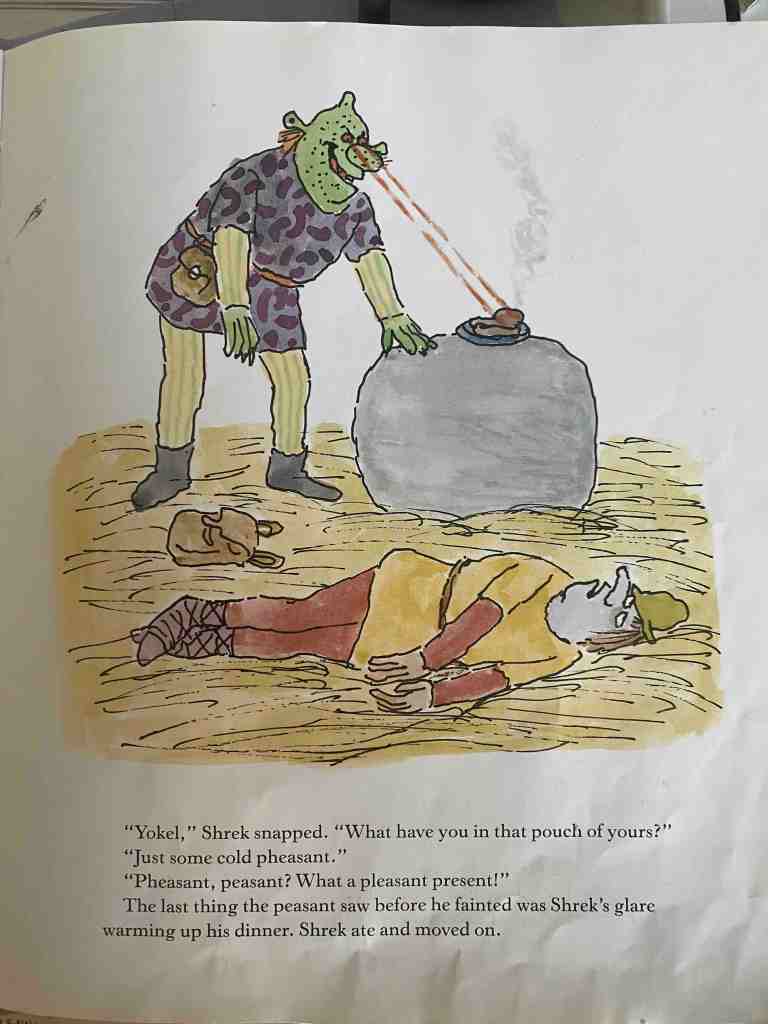

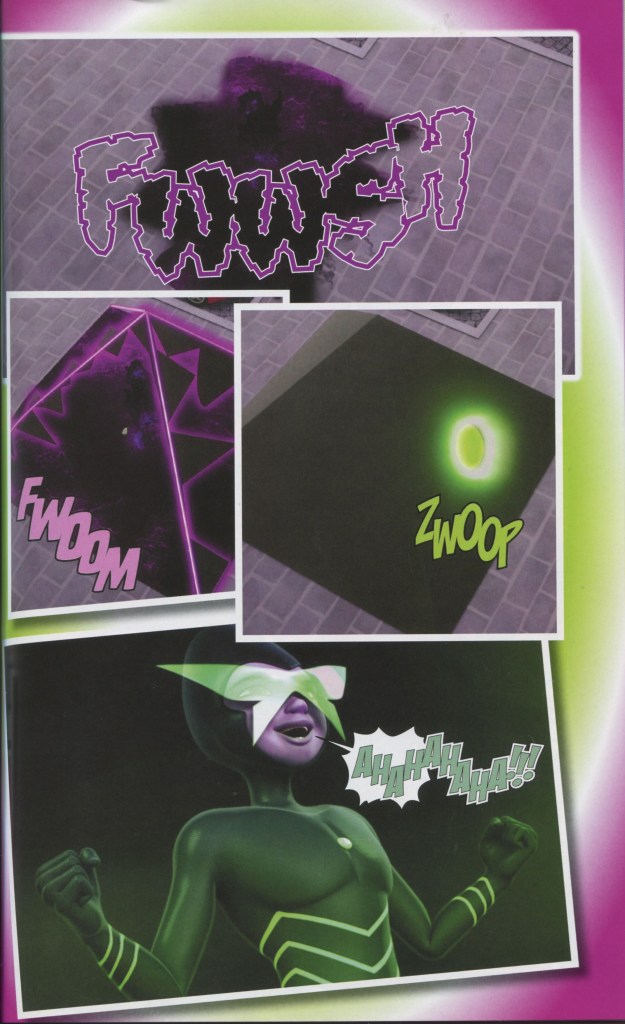

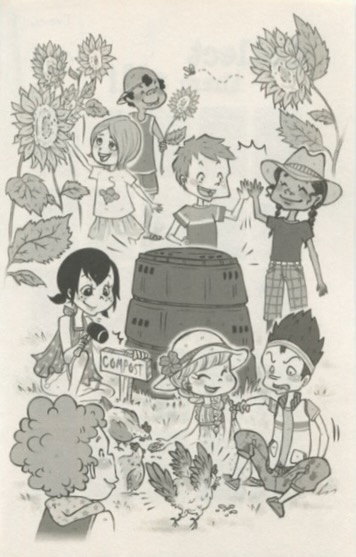

Rather than give more detailed summary, I’ll stick to my practice of looking at page 77:

It would be interesting to compare this with the equivalent section of the original novel. Certainly it would take a lot of words (three thousand for these three pictures?) to convey as much information about character and to move the plot along so far. (The next page does include aquite a bit more explanatory dialogue.)

The large dragon at the top is Scarlet, one of the powerful queens who not only wages war but is committed to keeping it going for its own sake. She knows of the prophecy and, having captured the dragonets, is out to humiliate and destroy them. She stands on a platform that overlooks an arena where, for her own entertainment, she stages fights to the death between dragons who have been taken prisoner.

The small, brightly coloured dragon in the intricate cage is Glory, one of the five dragonets. She is a rain dragon, despised by everyone except her companions as beautiful but lazy and generally useless. Scarlet has not condemned her to gladiatorial combat, but has arranged her as an artwork. In keeping with her reputation, she is apparently sleeping (no spoiler to tell you that she is actually wide awake, biding her time).

The square-snouted character at bottom right is Clay, a mud dragon, another dragonet and this book’s central character. He is currently chained to the top of a pillar overlooking the arena with his wings constrained, destined to fight and, Scarlet expects, die violently. So much of his character is revealed in this one frame: though he has just discovered his own precarious situation, his attention goes completely to Glory – alarmed at her vulnerability but also with sibling irritation at her passivity.

To tell the truth, part of my reason for reading this book was what an unsympathetic observer might call moral panic: I had heard my granddaughter exclaim from the seat of the car, ‘Why is there so much blood in this book?’ This is a girl who recoils from even the mention of blood in real life. Having read the book, I’m guessing that this young reader is in there for the story and at worst puts up with the so far extremely stylised violence and gore, at best uses it to work through some of her own fears and anxieties.

I don’t know if I’ll read on, but I’m tempted.