Alison Bechdel, Spent: A Comic Novel (Jonathan Cape 2025)

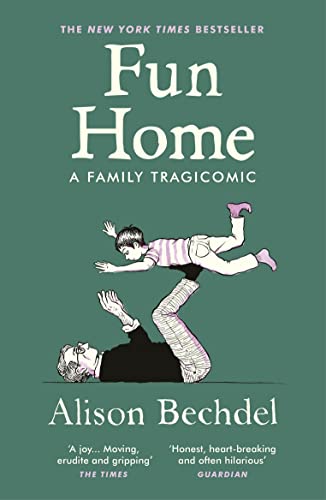

This is the fourth ‘graphic novel’ by Alison Bechdel. I use quote marks because they aren’t all novels. The first, Fun Home (2006), the only other one I’ve read, includes fictional elements, but is actually a memoir about her relationship with her father. I believe her second and third, Are You My Mother? (2012) and The Secret to Superhuman Strength (2021) are also predominantly memoirs.

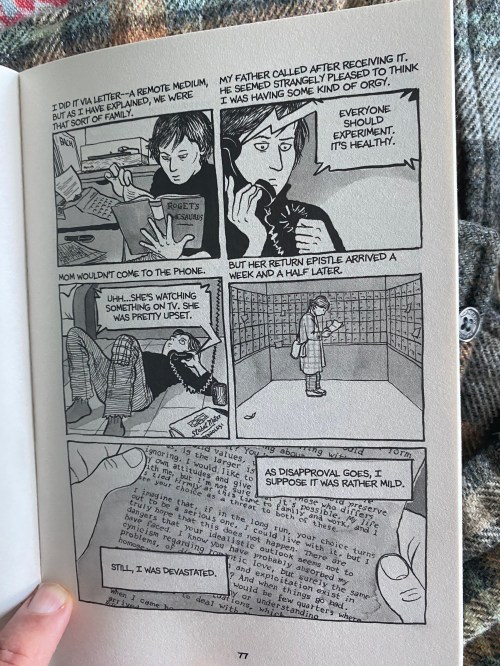

Even though this book describes itself as ‘a comic novel’, it too feels as if it’s taken from Bechdel’s actual life. The main character, ‘Alison Bechdel’, is a cartoonist whose graphic memoir about her father (here called Death and Taxidermy), became a best seller. The project she is currently working on has striking similarities to book we are reading. In the acknowledgements, the author thanks her ‘stellar agent, Heloise C. Bland Sydelle Kramer’ – the struck-through name belongs to the book’s fictional agent. And so on.

We’re not meant to read the book as describing the actual lives and loves of Bechdel and her ‘annoying, tenderhearted, and utterly luminous friends’. I don’t know if Bechdel has a goat farm IRL, or if her empty-nest neighbours are experimenting with polyamory (‘Indeed, they give “sandwich generation” a whole new meaning’). But the concerns and preoccupations of the characters are definitely taken from life.

This is a book about the members of a haven for leftist LGBTQI+ people in the era of Trump, MAGA, the climate emergency and rampant late-stage capitalism. They write letters, organise, lobby, have ‘Black Lives Matter’ placards on their lawns, argue about gender politics, suffer at the way television adaptation mangles and betrays Alison’s first book. And they are funny.

An early caption (page 14) sums up the mood: ‘How she rues the decades she spent fretting that the country was on the verge of fascism. Now it really is, and she’s worn out.’

Hence one meaning for the book’s title: spent, worn out, depleted. The title also refers to the way Alison and friends are incorporated into consumerism – the ‘S’ in ‘spent’ could have been a dollar sign, as in fictional Alison’s project, $um. The characters are constantly receiving packages from Amazon, and Alison agonises over whether to accept an offer from Megalopub (aka the Murdoch empire?) for her work in progress.

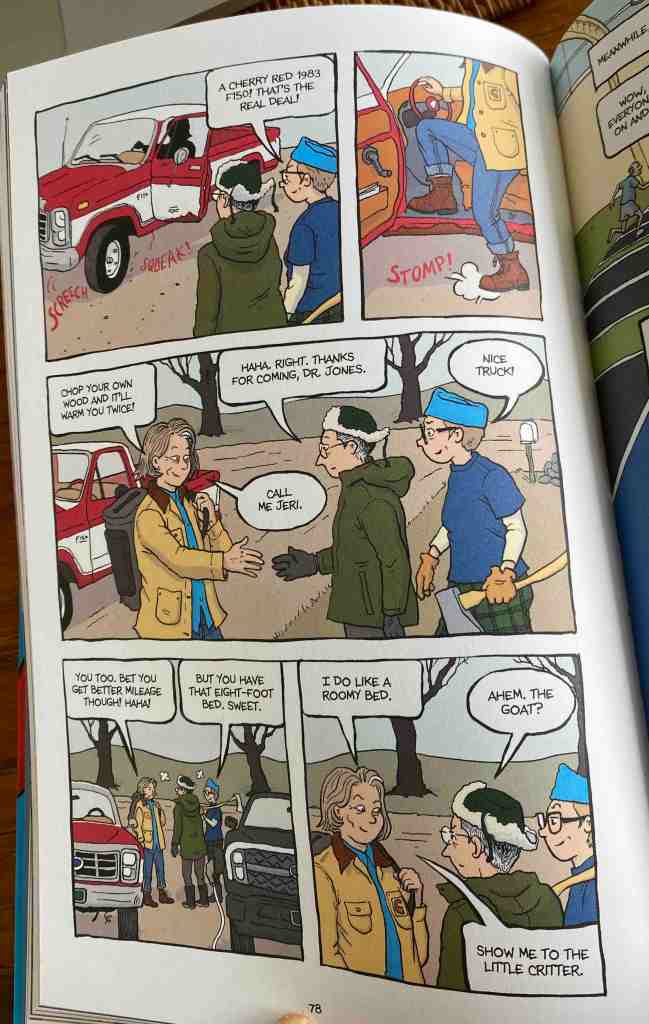

Page 78* gives you an idea of the art, and the general playfulness. A couple of pages earlier Alison and Holly have been startled out of their sauna by a goat thumping about on its roof – and have stood naked in the snow, rude bits discreetly hidden. A couple of pages later their neighbours are playing at the local pickleball palace and have a zing moment when hands touch that is the beginning of the polyamory thread. Page 78 is a quiet page: no nakedness, and just a couple of flirty double entendres.

Holly, in the blue cap, has been chopping wood while Alison films her for Holly’s Instagram account, which is about to go viral. ‘It’s the new vet,’ says Alison. ‘Whoa! What a beauty!’ says Holly. We turn the page and see that Holly is looking at the vet’s truck, not the vet herself.

But the original ambiguity continues. The flirty stuff between Holly and the vet will persist, making Alison a little nervous.

I notice two things about the page.

First, same-sex attraction is the norm in the world of this book, no big deal. One character is a trans man, but no one even mentions it – somewhere along the line he is shirtless and discreet scars from top surgery are revealed. The one cis-het man in the friendship group has fantasies of being a Lesbian. Even the women of the younger generation who identify as asexual are asexual with other women. Heterosexuality is, um, rampant among the miniature goats, which leads to some good-humoured comedy.

Second, there’s a tiny detail in the bottom left frame. No verbal cues given (unless that’s what the vet means about mileage), the car on the right is being charged. Of course, you think, these right-on environmentalist vegans would have an EV. It’s one of the pleasures of the book that such tiny moments abound. A random flick through the pages gives someone commenting at the communal non-Jewish shabbat, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever seen a man light the candles before.’ Or there’s the young gender-non-conforming character Badger wearing a T-shirt that proclaims, ‘Neurodivergent AF’. Monitor screens and floating strips of text regularly bring news from Mar-a-Lago and the disasters of the wider world.

Of my recent reading, the book this most chimes with is Susan Hampton’s memoir, Anything Can Happen. They are both excellent books. This one doesn’t have the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, but it’s funnier.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal, where the wind is cool and rain is pending. I acknowledge their Elders past and present and welcome any First Nations readers of the blog.

* That’s my age. When blogging about a book, I focus on page 78 to see what it shows about the book as a whole.