Andrew Burke, Historic Present (Flying Island Pocket Poets 2023)

The ‘About the author’ paragraph at the back of this book begins ‘Andrew Burke was an Australian author’ – and you realise that the Acknowledgements two pages earlier were written very soon before the writer’s death in his 79th year (as confirmed by his Wikipedia entry), and that one of the last things Andrew Burke wrote was this tiny love note:

The many moods of this collection were suffered in partnership with my wife, Jeanette – so thanks for discussions over blueberries and porridge.

The preceding ninety pages of poetry do reflect and capture many moods, and it’s not hard to imagine the man who wrote them enjoying a quiet chat over blueberries and porridge – not just with his wife but with a community of poets living and dead. Many of those poets find their ways into the verse, either by name or by quotation, very occasionally in a way that made me go googling, but mostly as a way of invoking a community, of readers as well as writers of poetry.

There are poems of travel and childhood memory, poems marking the death of a friend, poems that seem above all to be recording a passing moment. They don’t strive for effect or makes a song and dance of their emotional content or insights, but quietly do their work and are gone.

‘Testicular Check-up’, for example, begins:

I fell in love with my balls all over again when they were endangered.

(You’ve got to love those line breaks!) What follows is a good humoured conversation with the ‘lady’ scanning his testicles. He doesn’t spell out the emotional content of the moment. Enough to say that amid the chat and the matter-of-fact handling, first of his penis then of each testicle, he feigns comfort and indifference, the repetition of the word ‘feigning’ lying like a blanket over what is left unsaid.

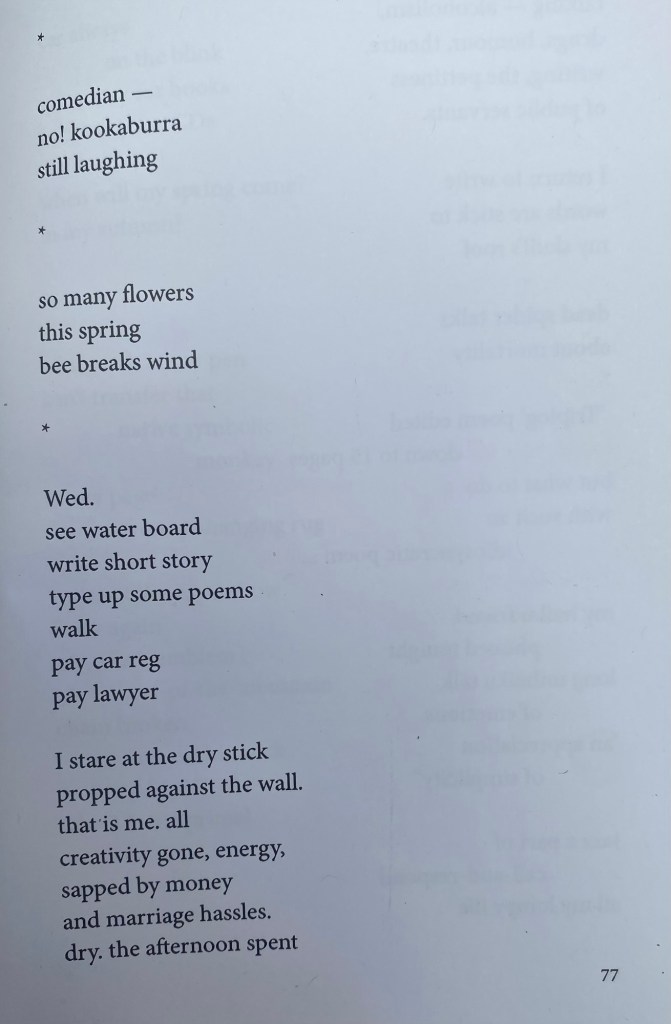

Page 77* falls in the middle of the book’s longest poem, ‘Lone Patrol: Darlington 1991’. Again looking to Wikipedia, I find that Darlington is a small community some distance east of Perth frequented by artists. The speaker of this poem is living in someone else’s cottage, perhaps an Airbnb (or the 1991 equivalent) or a writerly retreat, or just to take a break from a difficult time on his life. He chats with a visitor, attends an AA meeting, writes, listens to Jack Kerouac, reflects on his life, enjoys the surroundings.

The poem is in 23 sections, and reads like notes on his time in the cottage. These lines, from page 78, referring to work he is doing on another poem, shed light on the nature of this poem:

'Triplog' poem edited

___________ down to 15 pages

but what to do

with such an

________idiosyncratic poem ...

‘Log’ isn’t a bad description of the current poem – ‘staylog’ perhaps, part journal, part jottings of observations and reflection. And it’s not hard to imagine that it has been edited down from copious daily notes to its 14 pages. I usually look for an overarching narrative in long poems, but here I couldn’t see anything other than a string of moments – and I’m happy with that.

Page 77:

The first two sections are short haiku- or senryu-like poems.

The first, as I read it, juxtaposes the speaker’s grim mood (‘Comedian – / no!’) with the cheerfulness of the natural world, represented by kookaburra’s laughter. Whether the laughter is derisory (the kookaburra is laughing at the poem’s speaker) or simply indifferent (the kookaburra is just laughing without reference to him) is left open.

The second is less successful. I googled ‘Do bees fart?’ Apparently it’s an age-old question, and they sort of do but not really. My sense is that the poem doesn’t care about that. It catches itself in a cliche celebration of flowers in the spring, and throws in a bit of vulgarity to shake the image up. (It does make me want to echo the earlier lines: ‘Comedian – no!’, but in a friendly way.) You might enjoy the way ‘break wind’ has a second, more literal meaning – the bee interrupts the flow of the breeze. If so I’m happy for you.

The third section starts out as a prosaic to do list, then in the second stanza that prosaicness finds what in my distant university days was called an ‘objective correlative’ – an embodiment of the underlying emotion:

I stare at the dry stick

propped against the wall

The narrative behind the matter-of-fact notes ‘pay car reg / pay lawyer’ comes more fully into view – there may be a divorce in the mix:

_________ all

creativity gone, energy,

sapped by money

and marriage hassles.

dry.

The section goes on, to describe an afternoon of talking, and then of trying to write. It ends, taking the image of the dry stick one step further:

dead spider talks about mortality

Unlike the kookaburra, the dead spider (on a windowsill?) reminds him of his mortality; or perhaps he himself, dead-spider-like, can’t write of anything but death.

The poem is a staylog, and also a pretty matter-of-fact account of what a more egotistical person might have called a Dark Night of the Soul. In 1991, the poet was approaching 50. Perhaps the matter-of-factness was there at the time, or perhaps the poem got to its present form much more recently, and the matter-of-factness comes from the thirty-plus intervening years.

It’s a bitter-sweet thing to meet a poet only after he has died. But it is sweet.

I wrote this blog post on Gade / Wane. I acknowledge the Gadigal and Wangal elders past present and emerging, and gratefully acknowledge their care for this land for millennia.

* My blogging practice is to focus on page 77 (at least until I turn 78). In books like this, the practice saves me the impossible task of choosing one poem to represent them all.