Bill Ashcroft, The Gimbals of Unease: The poetry of Francis Webb (Centre for Studies in Australian Literature 1996)

Michael Griffith, God’s Fool: The life and poetry of Francis Webb (Angus & Robertson 1991)

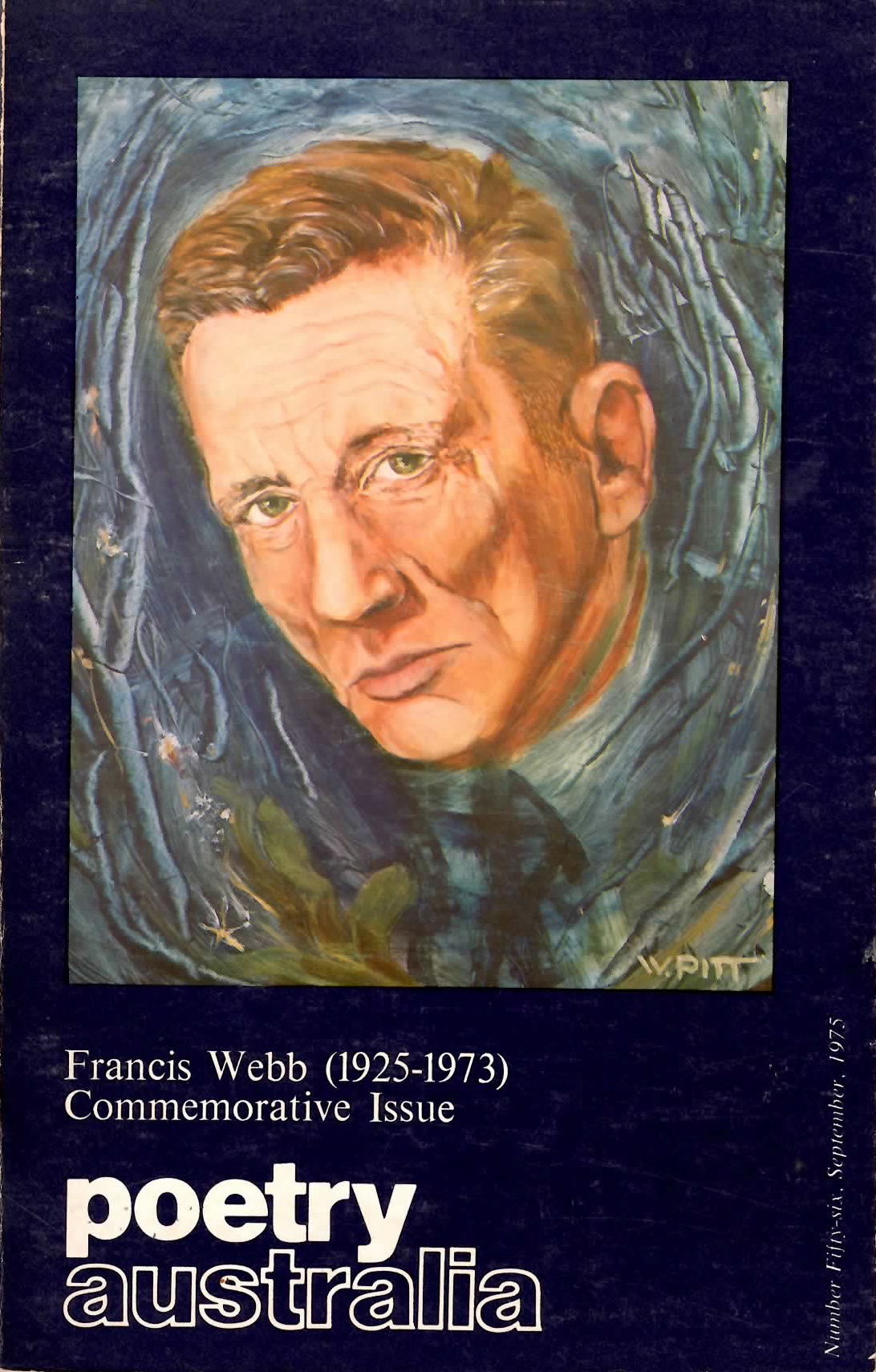

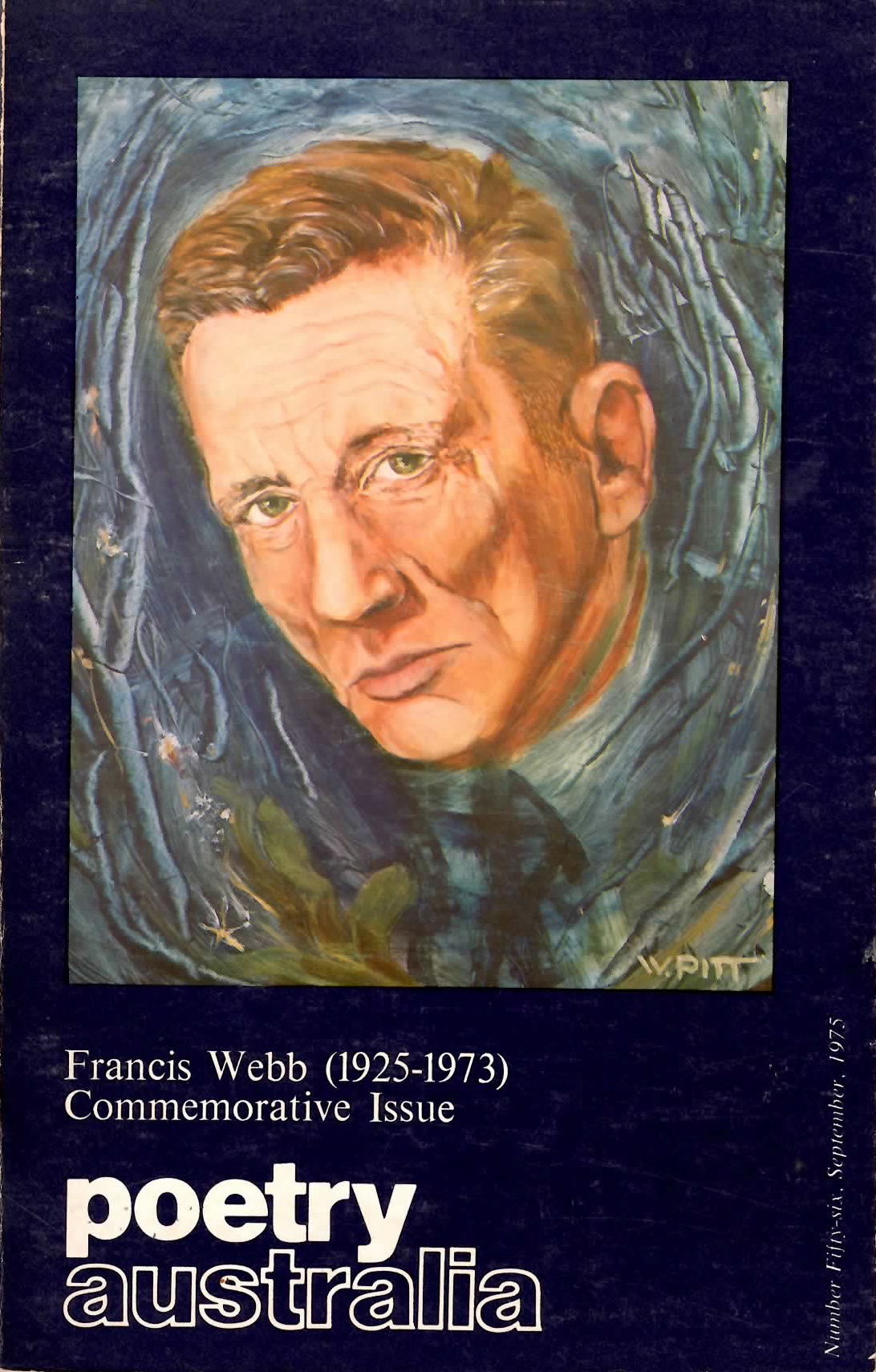

Poetry Australia September 1975: Francis Webb (1925–1973) Commemorative Issue

Peter and Leonie Meere, Francis Webb, Poet and Brother: Some of his letters and poetry (Old Sage Press 2001)

Having recently re-read Francis Webb’s collected poems, I didn’t want to just put the book back on the shelf. In order to be as booked-up as possible for the Sydney Writers’ Festival session on Webb next month, I got hold of three books about him, and dusted off my copy of the 1974 Poetry Australia commemorative issue. I can now assert that I have read every book published on the subject of Francis Webb.

Bill Ashcroft was writing an MA thesis on Webb in the Sydney University English Department in the early 1970s when I was a postgraduate student there. Michael Griffith was also in the Department then, and interested in Webb. Both of their books were published in the 1990s. Poetry as dense as Webb’s yields its riches slowly, so I was interested to read the results of such long gestations.

Bill Ashcroft’s emphasis is on explicating the poetry. He talks about Webb’s use of language, and about Webb as Catholic, as schizophrenic and as explorer. I believe Bill approaches Catholicism as an outsider, since he seems to miss references to Catholic liturgy and lore, but his analysis may be all the more useful for that, as he goes instead to major spiritual and intellectual traditions within Catholicism (namely the Thomist–Ignatian and the Augustinian) and locates tensions between them in the poetry.

Bill Ashcroft’s emphasis is on explicating the poetry. He talks about Webb’s use of language, and about Webb as Catholic, as schizophrenic and as explorer. I believe Bill approaches Catholicism as an outsider, since he seems to miss references to Catholic liturgy and lore, but his analysis may be all the more useful for that, as he goes instead to major spiritual and intellectual traditions within Catholicism (namely the Thomist–Ignatian and the Augustinian) and locates tensions between them in the poetry.

His discussion of schizophrenia reads as if it was mostly thought through in the 1970s when R D Laing and the anti-psychiatry movement hadn’t lost the battle with Big Pharma for domination. In my opinion it’s all the better for that. He argues that Webb’s extraordinary use of metaphor is intimately connected to the condition for which he was repeatedly hospitalised, drugged and subjected to electroconvulsive therapy; that people diagnosed as schizophrenic often don’t distinguish, as others do, between metaphoric and literal ways of thinking, that this is generally a brilliant way of dealing with impossibly painful situations rather than the symptom of an illness. In the section on Webb as explorer, he argues that Webb’s poetry is groundbreaking post-colonial work, holding ‘a balance between the European spiritual roots and the post-colonial vision’.

According to the book’s back cover, Bill Ashcroft has been a trailblazer in post-colonial studies. As might be expected, then, his prose is heavy with theoretical ballast, and occasionally reaches dizzying heights of abstraction. I expect book would repay close, careful study, but at least for now I’m happy to have read it in a companionable way: I might not understand a lot of what this bloke says, but it’s good to have listened to him talk at length.

Michael Griffith co-edited Cap and Bells, a selection of Webb’s poems that came out the same year as God’s Fool, so he’s probably done as much as anyone to keep the poetry in print for the last 20 years. This book is an offshoot of Griffith’s PhD Thesis. ‘In reducing the work from its longer academic form,’ he writes in his introduction, ‘I have tried also to introduce some aspects of Webb’s humanity which had less place there.’ For this departure from academic rigour, I for one am grateful.

Michael Griffith co-edited Cap and Bells, a selection of Webb’s poems that came out the same year as God’s Fool, so he’s probably done as much as anyone to keep the poetry in print for the last 20 years. This book is an offshoot of Griffith’s PhD Thesis. ‘In reducing the work from its longer academic form,’ he writes in his introduction, ‘I have tried also to introduce some aspects of Webb’s humanity which had less place there.’ For this departure from academic rigour, I for one am grateful.

When I studied Eng Lit we did a lot of close reading, and the idea of approaching literary work by way of the author’s biography was sneered at. Bill Ashcroft deals with such potential sneers by talking about the poetry and the poet’s life as two intersecting texts that illuminate each other. Michael Griffith doesn’t see the need for such justification, and just gets on with the illuminating. He does do some explicating of the poetry, but I found much more value in his delving into Webb’s life story than in any tight focus on the text. He draws on Webb’s letters and other documents, including two ‘Hospital Confessions’ written as part of campaigns to have him released from institutions. He quotes correspondence with Norman Lindsay, Douglas Stewart and David Campbell among Webb’s elders, and Rosemary Dobson, Nan Macdonald, Vincent Buckley and others of his contemporaries. One day a collection of Webb’s letters may see the light, but in the meantime this book draws on those that have been preserved by colleagues and family to show us a working poet who, in spite of long periods of incarceration and serious difficulty in coping outside of institutions, was a cherished and active member of a creative community. In particular, it is fascinating to learn details of his early connection to Norman Lindsay, and to consider his poetry of the 1950s in the context of the resurgence of Christian, even Catholic, themes in Australian poetry and art at that time.

The September 1975 issue of Poetry Australia was devoted to Webb, who had died nearly two years earlier. As well as several previously unpublished poems (all of them now available in Toby Davidson’s 2011 Collected Poems), it includes essays by Griffith, Ashcroft and other scholars, but its enduring interest lies in contributions from Webb’s fellow poets who knew him and appreciated his work – Rosemary Dobson, A D Hope and Vincent Buckley among them. There is also a poignant memoir by Sister M. Francisca Fitz-Walter, a Good Samaritan Sister who befriended Webb.

The September 1975 issue of Poetry Australia was devoted to Webb, who had died nearly two years earlier. As well as several previously unpublished poems (all of them now available in Toby Davidson’s 2011 Collected Poems), it includes essays by Griffith, Ashcroft and other scholars, but its enduring interest lies in contributions from Webb’s fellow poets who knew him and appreciated his work – Rosemary Dobson, A D Hope and Vincent Buckley among them. There is also a poignant memoir by Sister M. Francisca Fitz-Walter, a Good Samaritan Sister who befriended Webb.

These essays are a striking reminder of how the language of literary criticism has changed in the last 40 or so years. Compare Vincent Buckley, in his essay ‘A Poet of Harmony’:

He was a great phrase maker and

there are phrases, sentences, cadences in poem after poem that are quite

unforgettable. He was a great master, and sometimes a victim, of metaphor,

the most metaphor addicted poet in this country, I would say, and it is noticeable that time and time again the energy of those very ample driving

rhythms is also the energy with which metaphors are picked up, created

and extended through the stanza.

with Bill Ashcroft, 30 years later:

The compatibility of schizophrenia and the post-colonial, or to put it a different way, the schizophrenic discourse of post-colonialism, is seen most markedly in the similarity between the absence of the metacommunicative mode in schizophrenic language and [the] metonymic gap [of post-colonial discourse].

I don’t discount the importance of Bill’s theorising – on the contrary, it opens up great vistas of understanding. But Vin (as Webb called him) says a lot more about the immediate experience of reading the poetry.

Francis Webb, Poet and Brother is a labour of love, compiled and self-published by Webb’s younger sister and her husband in 2001, when they must have been in their 70s. It includes a number of poems that had not been previously published – but which are mostly in Toby Davidson’s collection. Its appendices include an impressive bibliography of critical writings about Webb; nearly 60 pages listing all his poems, the place and date of first publication, the place of composition where that’s known, and all subsequent publications; and 12 pages listing errors in those publications and in writings about Webb. All this will probably be of interest to scholars, but then there are the letters – 56 of them, written to his three sisters and his brothers-in-law from 1943 when he was 18 to a month before his death in 1973, with linking passages by the Meeres, including occasional quotes from other sources, such as for example Vincent Buckley’s memoir Cutting Green Hay – a quotation which, incidentally, tells a story of youthful drunkenness that Buckley hinted at but declined to tell in his Poetry Australia essay. If Webb’s letters to colleagues are as compelling, and poignant, and interesting as these, someone really ought to be getting a collection together.

Francis Webb, Poet and Brother is a labour of love, compiled and self-published by Webb’s younger sister and her husband in 2001, when they must have been in their 70s. It includes a number of poems that had not been previously published – but which are mostly in Toby Davidson’s collection. Its appendices include an impressive bibliography of critical writings about Webb; nearly 60 pages listing all his poems, the place and date of first publication, the place of composition where that’s known, and all subsequent publications; and 12 pages listing errors in those publications and in writings about Webb. All this will probably be of interest to scholars, but then there are the letters – 56 of them, written to his three sisters and his brothers-in-law from 1943 when he was 18 to a month before his death in 1973, with linking passages by the Meeres, including occasional quotes from other sources, such as for example Vincent Buckley’s memoir Cutting Green Hay – a quotation which, incidentally, tells a story of youthful drunkenness that Buckley hinted at but declined to tell in his Poetry Australia essay. If Webb’s letters to colleagues are as compelling, and poignant, and interesting as these, someone really ought to be getting a collection together.

Four things shine through: Webb’s great affection for his family, especially for Leonie and Peter Meeres; his Catholic piety (almost every letter ends asking to be remembered in the recipient’s prayers, and promising to remember them in his); his single-minded dedication to his calling as poet; and his mental anguish. The reason for his repeated confinement in psychiatric institutions remains (of course) obscure: he repeatedly insists that he is completely non-violent, but the letters are peppered with references to incidents such as ‘a silly brawl’. Whatever the reason, it’s heartbreaking to read his pleas for help, his assurances of his harmlessness, his wretched descriptions of himself as a no-hoper, and towards the end his warnings not to upset and possibly damage children by bringing them to see him in his abject state – and through it all, his piety, his affection and his hunger for solitude and peace enough to write poetry.

The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama lives in a mental hospital in Tokyo, and is able to go to her studio regularly. It may be that Francis Webb needed to be kept apart from the general community, for his own or other people’s safety, but that he lived a life of such deprivation must surely stand as a reproach to the way people labelled mentally ill have been treated in this country. Yet the miracle of it is that he too created marvellous works:

Are gestures stars in sacred dishevelment,

The tiny, the pitiable, meaningless and rare,

As a girl beleaguered by rain, and her yellow hair?

-33.875184

151.172380