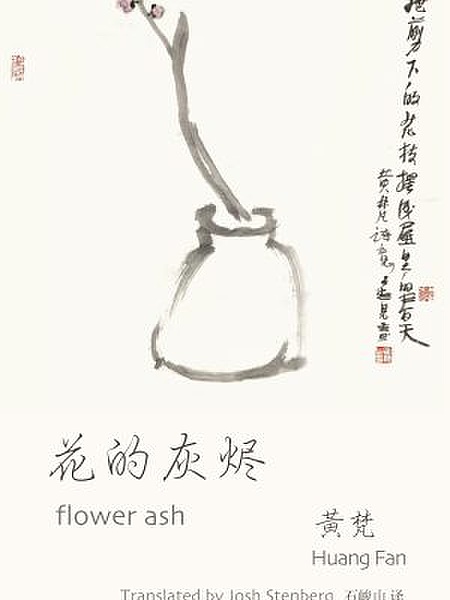

Huang Fan, Flower Ash (translated by Josh Stenberg, Flying Island Books 2024)

Huang Fan is a Nanjing-based poet and novelist who has received many awards and prizes in his homeland, and has been described as the Chinese mainland poet of most interest to Taiwanese readers. His work has been widely translated, including into English. Flower Ash is a wonderfully accessible introduction to his work.

The Flying Islands website (at this link) quotes US novelist Phillip Lopate::

In these powerful, exquisite poems, Huang Fan, a major Chinese poet, takes stock of his life from the vantage point of middle age, finding deep connections with nature, but also rueful solitude, memories of lostness, and a lingering sense of missed opportunities. These translations beautifully capture a threnody of wonder and sadness which is the poet’s singular achievement.

It’s a bilingual book. On each spread, Josh Stenberg’s English version is on the left and Huang Fan’s original Chinese on the right. Perhaps partly because of this, I was always aware, as I read, that the real poem, over there on the right, was inaccessible to me. (A bilingual reader would of course have a very different experience.)

The poem ‘Mayfly’ on pages 78* and 79 is a good example:

Don’t you just wish you could read those beautiful lines of characters on the right-hand page?

The English, by contrast, feels unadorned. The first two lines lay out the poem’s central idea:

we too are mayflies, knowing the four seasons

but living only in one season of a single day

Mayflies live for a single day. From some perspectives, our lives are similarly short.

The following lines present different images to represent the same idea: a lifetime is ‘a moment of the milky way’, the High Tang period (the eighth century CE, a golden age of Chinese poetry) is just a day, what we see as an ocean is just a stagnant puddle. And so on. It’s hard to see that anything much is happening that isn’t already there in the first lines.

I think the problem is translation. Not that Josh Stenberg’s translation is inadequate, on the contrary. But translation itself is problematic. I suspect the music of the original, and the visual play that’s happening in the ideograms, are simply untranslatable, and what we get is like a musical score, or a choreographer’s notes.

But even given all that, the poem takes an interesting turn:

with no chance to see the recesses of the mind

we treat a dewdrop like a shatterproof heart

The imagery is no longer straightforward illustration of a straightforward idea. These lines open out to something deeper, less easily paraphrased. It’s no longer the perspective of deep time or deep space that is being evoked but the depths of the mind and the complexities of human emotion. If it mistaken to think of the dewdrop as a shatterproof heart, is there an implied heartbreak, an unfathomable sorrow – even ‘a threnody of wonder and sadness’?

After briefly returning to a catalogue of oppositions – breeze/gale, lily pads/islands – the poem lands on this:

it seems that only the trees shade, the haze in our eyes

is praying: the leaves willing to fall from the branch

have souls the same as us

seizing transience fast with all their life, safeguarding

------- the fleeting vanities

This doesn’t yield coherence easily. I confess I got some help – I went to Google translate, and found this:

It seems that there is only the shadow of the tree - the haze in our eyes

is praying: may the leaves falling from the trees

have the same heart as us

Use your life to hold on to the short-lived and keep

------- the delusion of flying

Again, the Chinese text is a closed book to me, but to my ignorant eye, and to my astonishment, the robot makes better sense than the award-winning human translator. Instead of ‘only the trees shade’, which makes no easy sense, the mechanical translation has ‘there is only the shadow of the tree’ – that is, we don’t see the real world, but something like the shadows in Plato’s cave. Instead of the leaves ‘willing to fall’, it is the speaker who wills –’may the leaves falling’: it’s not a description but a prayer (which follows on from ‘praying’ at the start of the line). And in the last line it’s no longer the leaves ‘seizing transience’, but the reader being urged to do so. What we experience may be ‘fleeting vanities’ (much more resonant than ‘delusions of flying’, even though the latter fits the idea of falling leaves better), but it’s what we have, and we (‘you’ in the robot’s translation, ‘the leaves’ in the human’s) need to seize it fast / hold onto it.

I didn’t set out to do this, but I seem to have taken a single poem and demonstrated that reading poems in translation is fraught.

I did enjoy the book, and am glad that Flying Islands regularly include Chinese–English bilingual books.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal. I acknowledge Elders past and present of those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.