Ken Bolton, Metropole: New Poems (Puncher & Wattmann 2024 )

I’m more than a bit in love with Ken Bolton’s poetry, but I was at a loss what to write about Metropole without in effect repeating what I’d said about his three previous books that I’ve read (you can see those blog posts here, here and here).

Then I saw a headline on the Overland website: ‘The trouble Ken Bolton’s poems make for me, specifically, at the moment’ by Linda Marie Walker. Ah, I thought, someone who hates his poetry! Maybe they’ll point out ingrained misogyny or other cancellable qualities. Someone I can get into an argument with!

No such luck. The article is a very funny account of how Linda Marie Walker has enjoyed three of Bolton’s poems – where the word ‘enjoyed’ has complex meanings. All three poems she discusses appear in Metropole. Her ‘trouble’ with Bolton is partly summed up in this sentence:

These poems are, for me only, perhaps, enormous art museums with small and hopeful labels beside the works, just tempting enough to turn me into a rabbit sitting beside a trap at the mouth of the burrow/hole.

It’s not only you, Linda Marie.

So, rather than someone to fight with, I found someone who can describe the pleasures of these poems infinitely more satisfyingly than I can.

So I’ll stick with page 78*, which is the 12th of 14 pages of the poem ‘A Misty Day in Late July, 2020’, and has its own small and hopeful labels. It’s a Covid poem – specifically, according to one of Bolton’s delightful endnotes, Covid ‘as experienced by Adelaide: a “phoney war” situation as the city at the time remained relatively disease-free’.

The first lines of this page will seem melodramatic when presented without what has gone before:

True.

But must I die – must I die yet?

You could read the preceding pages as designed to blunt the force of that question. They have circled the subject of the Covid pandemic – describing family activities and a richly metaphorical fog on Bruny Island, quoting an ‘unflappable’ writer in the London Review of Books, remembering friends who have died long ago, and referring to movies and TV shows of tangential relevance. Somehow the poem arrives at the 1970s WWII TV series The Sullivans, and Bolton/the speaker remembers that ‘the Sullivans’

_____________________ _______________ became

appropriately, a name for Australians

or Anglo types ... as used by Indigenous Aussies ...

or Greeks & Italians

He supposes he is ‘one of them’ and says he ‘must die a Sullivan’. Almost by accident, it seems, he has explicitly acknowledged the prospect of his own death – and the stark threat from Covid is momentarily present.

True.

But must I die – must I die yet?

The rest of the page is a lovely example of the way Bolton’s poetry fizzes with allusion. (I’m reminded of a favourite line from Martin Johnston: ‘Even my compassion reeks of libraries.’) First, in recoiling from the thought that Covid might kill him, expresses the recoil by quoting from an old movie:

& now I say, Rick, Rick, you’ve got

to save me (Peter Lorre)

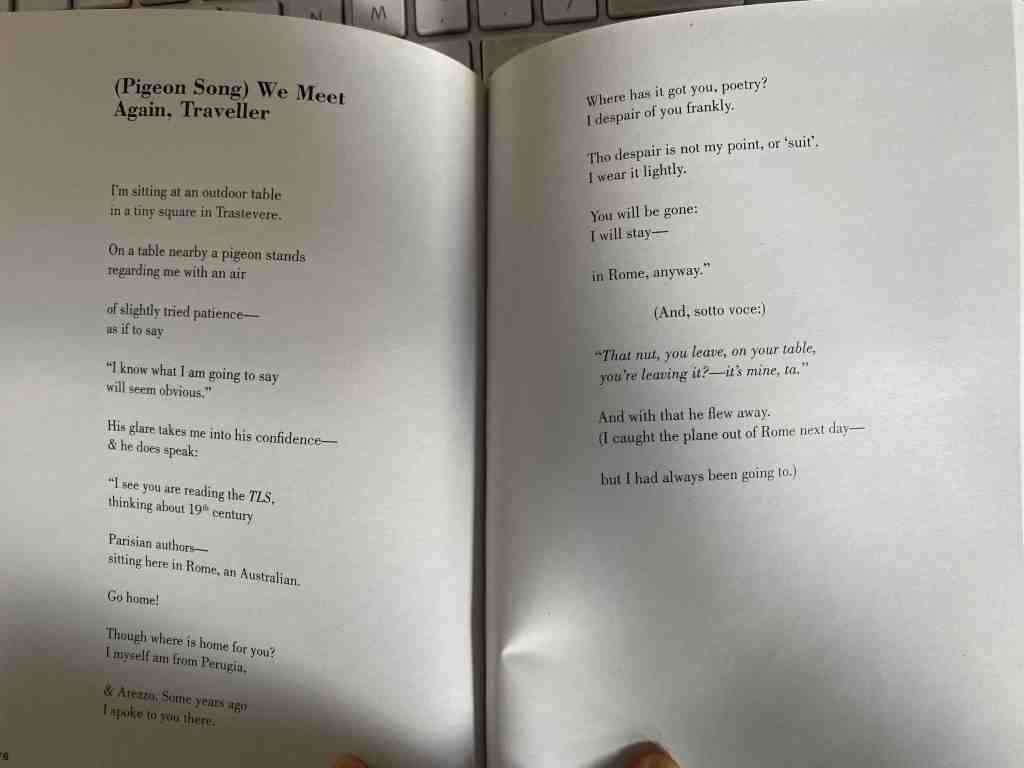

That’s from Casablanca, which has been mentioned earlier in the poem because of the fog. I went down that little rabbit hole to watch the scene on YouTube. The actual line is, ‘You must help me, Rick. (Then, as he is being dragged away) Rick! Rick!’ This is not an academic exercise where the quote needs to be exact – the line is quoted as it sits in the poet’s memory.

It turns out that the quote is a bridge back to safe ground. Mention one classic story, and the mind can go to another, and at the comfortable remove provided by sales figures. He also finds reassurance by putting ‘in a big way’ in minimising quote marks:

Camus' The Plague has been selling well,

since the pandemic got started, (or got started 'in

a big way').

And then he’s away, play on associations with the foggy scene outside.

a big way'). And – since then – I think

'Mediterranean France', 'Nice', 'Marseilles'

(& see images of sweeping, empty

coastal roads curving round a bay)

(Matisse might have worked here)

An image based on a mixture of ... what towns? –

Trieste, Wellington, the Cannes of To Catch a Thief, Hvar –

Bolton is well-travelled. I haven’t been to Trieste, hadn’t heard of Hvar, and have to do a bit of mental calisthenics to see what Wellington and the Cannes of To Catch a Thief have in common – I guess it’s the coastal roads and steep hillsides. A reader could get hung up on not knowing the town referred to, or wondering about Matisse landscapes (and I did just google “Matisse landscapes”). The effect, though, is to find distraction / refuge / escape (?) – the poem’s speaker has travelled in his mind to faraway places, to works of art.

In the last lines on the page, he progresses in his escapist reverie from an image, to an atmosphere, to a scenario. In the final couplet, death again shoulders its way into the picture, to be turned away from in a whiplash switch to images from the old movies:

– where a killer might've killed someone,

where women wore high shoulders & calf-length dresses

When I read the poem for the first time, I confess I just went with the flow, enjoying the back and forth of image and allusion, picturing Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant in their convertible on the Corniche. Only reading it now with hands on the keyboard, I can go some way to articulating what’s happening. The final lines of this poem, two pages further on, make new sense to me:

The West has invented

some great glass-bead games

& I have been a sucker for all of them

Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game is another classic work I haven’t read. According to Wikipedia, the game ‘is essentially an abstract synthesis of all arts and sciences’ which ‘proceeds by players making deep connections between seemingly unrelated topics’. Not a bad description of what happens in Bolton’s poetry in general, and this one in particular. But Bolton doesn’t present himself as a polymath champion of the game. Polymath he may be, but that just makes him a sucker.

This is poetry that cries out for a collaborative reading. Or maybe it’s me that’s crying out – not ‘you’ve got / to save me’ but ‘come and enjoy this with me!’

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, as the days are starting to get longer, and the banksia are in flower. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their millennial long, and continuing custodianship of this land.

* My blogging practice, especially with books of poetry, is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.