Esther Anatolitis (editor), Meanjin Vol 84 Nº 1 (Autumn 2025)

(links are to the Meanjin website: I believe that they are now all accessible to non-subscribers)

Unless Melbourne University Publishing’s recent decision to shut Meanjin down ‘on purely financial grounds’ is reversed, this is the fourth-last issue of Australia’s third-longest-lived literary magazine. (The New South Wales School Magazine, a literary magazine for children, is the longest lived. Southerly comes second.) The two part-time employees responsible for the journal have lost their jobs. Even given the long list of other people whose work goes into each issue, it’s astonishing that this extraordinary publication has been produced by so few paid workers.

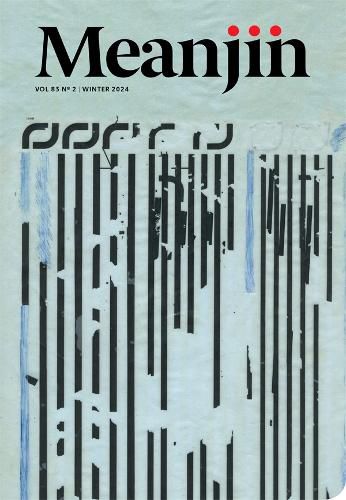

The cover design is weirdly prophetic. It represents the predictive results for a web search for “the work of”. Early this year, readers would hardly have noticed the battery icon in the top right showing a dangerously low charge, a speck of red on a mostly black page. Now, thanks to what has been correctly described as outrageous cultural vandalism, the battery is dead flat. But that’s the only sign of imminent demise. The rest of the issue – more than 200 pages of text and image – is as lively, varied and thought-provoking as you could wish.

There are the regular features:

- Even before the contents page, there’s The Meanjin Paper, an essay by a First Nations writer: ‘Different Plants for Different Meanings‘ by Anyume John Kemarre Cavanagh with Gabriel Curtin reads like poetry

- State of the Nation: topical essays, this time it’s Sisonke Msimang, Andrew Lemon and Rachel Withers on the Voice referendum, gambling and the housing crisis respectively, each with a twist

- Australia in three books‘: Sarah Walker writes about Ethel Turner’s classic children’s book Seven Little Australians, Jessie Cole’s Desire (2022) and Helen Garner’s Yellow Notebook (the first volume of her published diaries), all of them dealing with girls or women who ‘are trapped in the great looping flood’ of their feelings

- Interview: It’s Winnie Dunn, author of the novel Dirt Poor Islanders and mover and shaker in the Western Sydney’s rich literary scene, and it makes very interesting reading

- The Year In … : The year in Yellowface. Jacqueline Lo focuses on the web trailer for a ballet production at the 2024 Adelaide Festival, which she argues represents a persistence in Australian culture of attitudes to Asian characters and actors that are no longer tolerated where Blackness/Blakness is the issue.

There are short fictions, memoir, essays, book reviews and poetry. I’ll name just one or two of each.

In the short story ‘The farmer‘ by Suzanne McCourt, the title character is a woman of a certain age searching for a calf that has gone missing, presumed stolen by her neighbour. There’s a lot there for any reader to like, but because I spent a lot of time with cattle when I was young, I particularly loved the way the story captured the intimate bond between human and cows and their calves, including the delicate process of adoption.

Of the four pieces labelled ‘Memoir’, Jess Lilley’s ‘My pregnant life‘ stands out. It begins with the author’s first pregnancy when she was nineteen and dealing with the legal and social hurdles to abortion. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to quote the essay’s last words:

When I lay with his tiny body in my arms, I knew this signalled the end of my pregnant life. Nine pregnancies across 25 years. A quarter of a century of having my world rocked over and over and over by my own bodily forces.

‘minganydhu ngindhumubang / What am I without you?’ by Tracy Ryan is a generous bilingual essay in a class of its own that challenges readers to deconstruct our assumptions and practices around language – much of it is written in Wiradyuri language, first transliterated then translated: ‘my soul wants to decolonise language but that would make this work nearly incomprehensible to an English-dominant culture.’

Architect Naomi Stead’s essay ‘Wheatscape with Cathedral‘ deals with the extraordinary Stick Shed in Murtoa, rural Victoria. The author’s full-page photo of the shed’s interior cries out for an explanation of the extraordinary vision, and the article more than satisfies.

Of poetry, I’ll mention just ‘Sacrificed on Altar of Vice’ an erasure poem by Brittany Bentley. If you click on the link, you’ll see the image of two columns of newspaper copy most of which has been redacted in red. The words that are still legible constitute the poem. The hard-copy Meanjin includes a link to the unredacted article. The poem stands on its own feet but read in conjunction with the original article its power is greatly amplified. Most of the poem’s title comes from the redacted text.

The three book reviews tend to be in rarefied scholarly language. Here’s a sentence from ‘Queer perforations‘, a review by Dylan Rowen of Blackouts, an experimental work of fiction by Justin Torres:

Determined to free the queer subject from the realm of the symbolic and to give voice to those erased from history, this text critically fabulates – to borrow Saidiya Hartman’s term – a history gleaned from the redacted bits of what little was left in the records.

Mercifully, this kind of insider language is mainly restricted to the book reviews.

With any luck, by the time I’ve read the final issue, in who knows how many months’ time, Meanjin, like Heat before it, will manage some kind of resurrection, in spite of Melbourne University’s reported refusal to entertain many offers of financial support from other institutions.

I finished this blog post on the land of Bidjigal and Gadigal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge their Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.