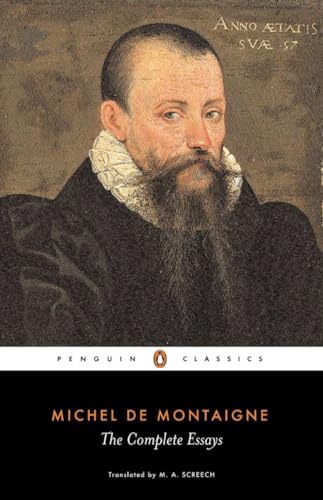

Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays (Penguin Classics 1991, translated by M. A. Screech) Book 1, from part way through Essay 26, ‘On educating children’, to Essay 41, ‘On not sharing one’s fame’

I’m enjoying my morning read of Montaigne, now at the end of my second month.

As expected, his name has cropped up elsewhere. The time I noticed was on Waleed Aly and Scott Stephens’s podcast The Minefield, when talking about the recent stabbings in Sydney. Scott referred to the essay that M. A. Screech translates as ‘On Affectionate Relationships’ to illustrate something he was saying about grief.

That essay was one I read this month. Though its discussion of grief is wonderful, the thing that stands out for me in it is his exalted notion of friendship. The meeting of souls that these days tends to be identified, hopefully, as part of romantic love he sees as quite distinct, and separate, from the love of spouse (he says ‘wife’) or children. Revisiting them now, I see that the paragraphs on grief are wonderful. For example:

I drag wearily on. The very pleasures which are proffered me do not console me: they redouble my sorrow at his loss. In everything we were halves: I feel I am stealing his share from him. (Page 217)

The essays I have just read are ‘Reflections upon Cicero’ and ‘On not sharing one’s fame’. I wish my Latin teachers could have told me about the Cicero one in high school: it would have made it much more fun to study that ‘Cui bono?’ speech if I’d known how Montaigne despised its author. Speaking of Cicero and Pliny the Younger, he writes:

What surpasses all vulgarity of mind in people of such rank is to have sought to extract some major glory from chatter and verbiage, using to that end even private letters written to their friends; when some of their letters could not be sent as the occasion for them had lapsed they published them all the same, with the worthy excuse that they did not want to waste their long nights of toil! How becoming in two Roman consuls, sovereign governors of the commonwealth which was mistress of the world, to use their leisure to construct and nicely clap together some fair missive or other, in order to gain from it the reputation of having thoroughly mastered the language of their nanny! (Page 279)

Then, wonderfully, two pages later in ‘On not sharing one’s fame’, in discussing the way ‘concern for reputation and glory’ is the most accepted and most universal of ‘all the lunacies in this world’ he writes this, without a trace of his earlier disparagement:

For, as Cicero says, even those who fight it still want their books against it to bear their names in the title and hope to become famous for despising fame.

But then, he regularly says that he has a poor memory.

The very last thing I read this morning is a wonderful example of how Montaigne can surprise and delight (though it’s also an example of the violence that permeates Montaigne’s world). He has been piling on examples of people (all male) who have acted to enhance someone else’s fame and glory, often to the detriment of their own. Then, in the last couple of sentences he swerves off into a comic non sequitur:

Somebody in my own time was criticised by the King for ‘laying hands on a clergyman’; he strongly and firmly denied it: all he had done was to thrash him and trample on him. (Page 289)

This blog post, like most of mine, was written on Gadigal-Wangal land as the days grow shorter and spiderwebs multiply, even in the heavy rain. I acknowledge the Elders past, present and emerging of those Nations.