Michael Mohammed Ahmad & Felicity Castagna (editors), On Western Sydney (Westside Publications 2012)

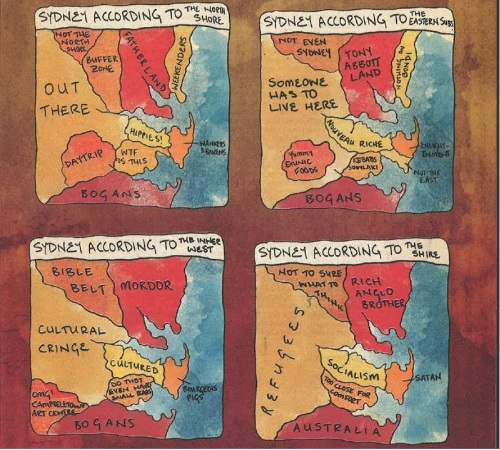

In early 2011, an issue of the University of New South Wales’ student newspaper Tharunka had a cover illustration of maps of Sydney according to four different regions. Like Yanko Tsvetkov’s stereotype maps, their probable inspiration, they manage to be cheerfully offensive about just about everyone, but you’d have to be thin skinned to take serious umbrage.

All the same, look at Western Sydney: ‘out there’, ‘someone has to live there’, ‘yummy exotic food’, ‘cultural cringe’, ‘refugees’, ‘day trip’. The anonymous cartographer has caught something, but if you stop and think for a bit you realise that he/she/they has/have surely pulled her/his/their punches, avoiding any references to drugs, sexual violence, Islamophobic stereotypes or the class attitude invoked by the word westies. More interestingly, there is no ‘Sydney according to Western Sydney’ map. Evidently, in the mind of the maps’ creator(s), Western Sydney lacks a view of its own.

Westside Publications exists to create a counter-narrative: to provide a platform for Western Sydney voices and, at least in part, to undermine the stereotypes, less by denying them outright than by seeking to paint a fuller picture. ‘I don’t mind a story that makes us look bad,’ writes Michael Mohammed Ahmad, chief editor of Westside, in his introduction to On Western Sydney, ‘so long as it’s honest and complex.’

Under the auspices of BYDS (Bankstown Youth Development Service), Westside has work for years in schools and the community to develop skilled writers. On Western Sydney is their twelfth anthology featuring established and/or emerging writers and artists connected to the region. Ahmad says the goal has been ‘to source writing from Western Sydney and writing about Western Sydney’. Of course it’s not the only place where writers from Western Sydney get published – in my time at the School Magazine, for instance, some of our regular contributors were from the west, and off the top of my head eminent poets Jennifer Maiden and Peter Minter have strong Western Sydney connections. And a number of the writers in this anthology have been published elsewhere, including in the definitely Inner West This is the Penguin Plays Rough Book of Short Stories. But there’s no doubting the significance of Westside. Last week Mohammed Ahmad received the Australia Council’s Kirk Robson Award which honours ‘outstanding leadership from young people working in community arts and cultural development, particularly in the areas of reconciliation and social justice’.

So On Western Sydney is a phenomenon. It’s also a good read, and not at all the dry sociological collection the title might suggest. It includes short stories, poetry, absurd parables, a photo essay; there’s lyricism, satire, rap, stinging social commentary, domestic observation, fantasy, memoir (I think), travel writing … from as culturally diverse a bunch of writers as you’re likely to find anywhere. Many of the contributors are familiar from Westside’s readings at recent Sydney Writers’ Festivals, and scattered throughout are Bill Reda’s photos of Moving People, this year’s event.

So On Western Sydney is a phenomenon. It’s also a good read, and not at all the dry sociological collection the title might suggest. It includes short stories, poetry, absurd parables, a photo essay; there’s lyricism, satire, rap, stinging social commentary, domestic observation, fantasy, memoir (I think), travel writing … from as culturally diverse a bunch of writers as you’re likely to find anywhere. Many of the contributors are familiar from Westside’s readings at recent Sydney Writers’ Festivals, and scattered throughout are Bill Reda’s photos of Moving People, this year’s event.

I wouldn’t rush to say that the stereotypes are completely repudiated. Some are reversed with varying degrees of subtlety. Two poems – Andy Ko’s surreal ‘A South Line Travel Guide’ and Fiona Wright’s deliciously ironic ‘Roadtrip’ (which begins ‘And it certainly felt like a Food Safari, such a long way from Kirribilli’) – could be read as direct, mocking responses to Tharunka‘s ‘day trip’ and ‘yummy exotic foods’ stereotypes. Predatory men are scarily realised in Amanda Yeo’s train-story ‘Nine Minutes’ and Frances Panapoulos’ poem ‘”puss puss”‘, though there’s no racial profiling in either. The class attitudes not quite articulated by Tharunka are challenged throughout, as when the protagonist of Peta Murphy’s ‘Roughhousing with Aquatic Birds’ suffers through some kind of arty inner west event (‘She doesn’t speak to me, / it’s as if she can see my Bunnings uniform’). The world evoked in Lachlan Brown’s long poem ‘Poem for a Film’ could well be labelled ‘Someone has to live there’, but there’s art – and heart – in the telling:

______On a blistering afternoon

a council truck is removing tall trees

so that no one will confuse this vista with

a place of moneyed elegance. And maybe

the scream of the chainsaw means you’re

not ignored, as cut limbs crash through

the dry air. And maybe what’s left is

for your own good, and the streetscape

becomes a mouth mashed up during a bar fight,

with its bare stumps grinning cruelly in the heat.

My guess is that the writers are mostly under 35. The problems of negotiating relationships is a dominant theme: under the judgemental gaze of older Arab women in Miran Hosny’s ‘The Weight Divide’; by phone in Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s own brief contribution, the deeply unsettling ‘The First Call’; in the gap between the world of song and the world of experience in Luke Carman’s ‘Becoming Leonard Cohen’ (though it’s pretty impertinent to describe Carman’s weird tangential verse as about anything); in bitter-sweet recollection of a high school crush in Tamar Chnorhokian’s ‘Remembering Leon’.

There’s so much to like. We’re told that this will be Westside’s last print publication. Maybe there’s a sense that its work is done, and the writers it has fostered can now find platforms further afield – in Asia Literary Journal, for example, whose current issue has a number of pieces exploring migrant identity. I hope so.

I received my copy free from BYDS. You can buy one from independent book shops in Sydney or directly from BYDS (email in@byds.org.au with your postal address and they’ll give you details on cost and bank transfer details).