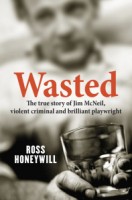

Tonight we went to hear Bob Ellis launch Ross Honeywill’s Wasted, the true story of Jim McNeil, violent criminal and brilliant playwright. There wasn’t a huge crowd – after all it’s nearly 30 years since Jim McNeil died,and his four plays haven’t had a production on a main stage for a long time. But it was a great launch, and looks like a very interesting book

Jim McNeil (1935–1982), according to the Gleebooks web site, quit school at thirteen. Despite his love of reading and philosophy, as a teenager he lived among thugs and thieves. (When we showed him a draft biographical note for one of his Currency Press books in the 1970s, he crossed out the word ‘criminal’ referring to his early milieu and replaced it with ‘knockabout’.) In 1967, shot a policeman during an armed robbery. He was convicted and began a seventeen-year prison sentence. In Parramatta maximum-security prison he joined a debating group known as the Resurgents. Though he’d never seen the inside of a theatre he wrote one-act plays for the group to perform: The Chocolate Frog and The Old Familiar Juice. These plays were given productions at the Nimrod Theatre in Sydney, were a big success, and were published by The Currency Press (the first book I ever copy-edited). He wrote another, full-length play, How Does Your Garden Grow, and part of a fourth, Jack, while still in prison, and then was released ten years early thanks at least in part to lobbying by members of Sydney’s theatre scene. As Ellis said tonight, people were imagining him as being like other badly behaved writers like Brendan Behan, but he was something else altogether. Once he was released he never wrote anything decent again, and his life was a slow descent into violence, alcohol-related illness, and eventually death.

Jim McNeil (1935–1982), according to the Gleebooks web site, quit school at thirteen. Despite his love of reading and philosophy, as a teenager he lived among thugs and thieves. (When we showed him a draft biographical note for one of his Currency Press books in the 1970s, he crossed out the word ‘criminal’ referring to his early milieu and replaced it with ‘knockabout’.) In 1967, shot a policeman during an armed robbery. He was convicted and began a seventeen-year prison sentence. In Parramatta maximum-security prison he joined a debating group known as the Resurgents. Though he’d never seen the inside of a theatre he wrote one-act plays for the group to perform: The Chocolate Frog and The Old Familiar Juice. These plays were given productions at the Nimrod Theatre in Sydney, were a big success, and were published by The Currency Press (the first book I ever copy-edited). He wrote another, full-length play, How Does Your Garden Grow, and part of a fourth, Jack, while still in prison, and then was released ten years early thanks at least in part to lobbying by members of Sydney’s theatre scene. As Ellis said tonight, people were imagining him as being like other badly behaved writers like Brendan Behan, but he was something else altogether. Once he was released he never wrote anything decent again, and his life was a slow descent into violence, alcohol-related illness, and eventually death.

I hesitate to say I knew Jim, but I did visit him in Goulburn Gaol with my then boss, Managing Editor of Currency Press Katharine Brisbane, and he came to our office more than once after his release. I remember one memorable lunch when he and Peter Kenna, author of A Hard God, told anecdote after anecdote in fierce competition, to our great entertainment. I wasn’t there when, in response to some imagined insult, he broke a bottle on the edge of the kitchen table and threatened to use it on Philip Parsons, Katharine’s husband – but I heard the story from the horse’s mouth the next day. Katharine said she laughed and said, ‘Oh Jim, put it down,’ and he did.

Katharine was there tonight. So were a number of others who knew Jim, including David Marr, who gave him a roof on his release from prison. Ellis also shared a flat with him for some time. Bob Ellis read a piece that sounded as if he had written it soon after McNeil’s death, conveying his charm, his brilliant use of language (‘Dustbin of the Yard here. How are ya, Bobby?’), the ever hovering possibility of violence, and his chaotic alcoholism. Then he read from Wasted, and there was no doubt we were talking about the same man. I’d rate it just about the most moving launch I’ve ever been to. It didn’t turn away from Jim’s truly ugly qualities (Honeywill said that the thing that most surprised him in researching the book was how very violent Jim had been – a far cry from the charming ratbag one would wish him to have been). But there were people who loved him, and still hold a tender place for him. A number of people from the audience told anecdotes, both about his charm and his dangerousness. His story was one of redemption through discovering the life of the mind in prison, then returning to the damned space, almost by an act of will. It made me think – and someone may have said this – that the damage inflicted by the prison system runs very deep: he had lost the ability to make the kind of quotidian decisions necessary to a decent life. Ellis did say that imprisonment has been an experiment in dealing with criminal behaviour, and it has failed.