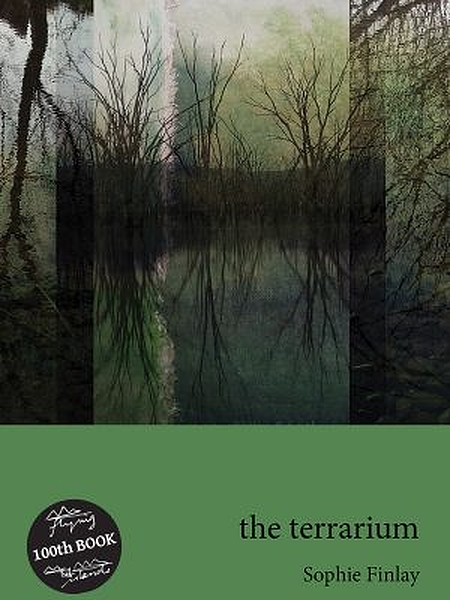

Sophie Finlay, The Terrarium (Flying Island Books 2024)

Sophie Finlay won the Flyng Islands Manuscript Prize for Emerging Poets 2022. A visual artist as well as a poet, she designed the book, and both the cover image and the photographs and delicate drawings scattered throughout are hers. It’s a beautiful, pocket-sized object.

The poems cohere around a main theme, summed up nicely in the final words of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, which serve as a kind of epigraph:

whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

As I understand it, the central idea of the book is to imagine the earth as a gigantic terrarium, in which one can observe the wonders of living things, often with scientific labels attached (poem titles include ‘Zooxanthellae’, ‘Morphologies of Ice’, ‘Glossopteris’ and ‘Noctilucent’), reaching back to the very beginnings of life, but including accidental personal matters such as a fear of snakes and a trip to Antarctica.

Interspersed among the other poems are six ‘extinction’ poems. Each of the first five of these comes with an indication of date: from the End-Ordovician extinction 455-430 mya (million years ago) to the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction 65 mya. The fifth, which is also the book’s final poem, refers to the Anthropocene extinction, no date necessary. These numbered poems aren’t section headings: in the midst of much else, they sound an ominous background drumbeat. Individual poems pay attention to detail but, just like in the real world, there’s a deep current that cannot be ignored.

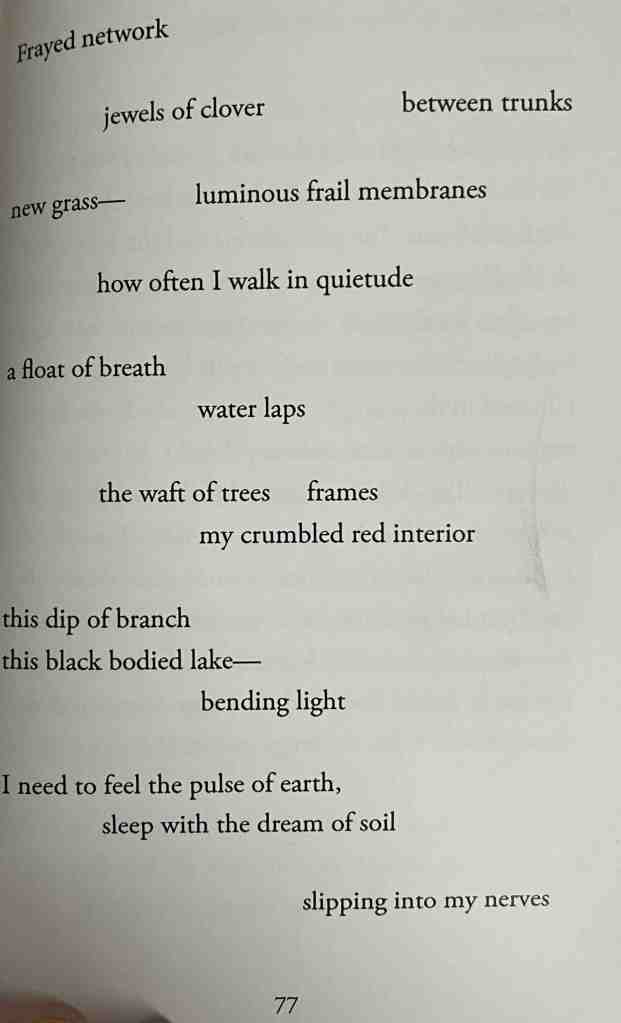

‘Frayed network’ on Page 77* is a moment when the ominousness is mostly at bay, there is no scientific nomenclature, and attention is on the present moment in the natural world.

This poem might be a nice entry point for readers who are intimidated or bewildered by contemporary poetry. It’s definitely one that could have prompted the question a friend of mine asked at a Sydney Writers’ Festival session, ‘Why have modern poets given up rhyme and metre?’. The words are spread out all over the page, I imagine my friend complaining, the punctuation is mostly no help, and where are the verbs?

But slow down, spend a little time, and I think even my indignant friend might find pleasure here.

The poem takes its readers on a walk among trees beside a lake. Line by line, the speaker notes details from the environment: the jewel-like clover, the luminous frail membranes (what a lovely phrase!) of new grass, the sounds of lapping water and the feel of a breeze. There’s a hint that this is a new beginning: at the end of a drought, perhaps or in the aftermath of a bushfire. When else would you think of grass as frail? These details are just there, each its own thing, with no attempt to tie them into a pattern or narrative with a formal rhyme scheme or metre, or sentence structure, or even an orderly presentation on the page. There’s a lot of white space, a visual equivalent of silence.

It’s a mindful kind of walking, just noticing, not trying to make meaning or extract usefulness.

Then, interspersed among the images there are three sentences, each of them about the speaker:

How often I walk in quietude

At the third line, the poem’s speaker and her situation is made explicit. ‘Quietude’ is a formal word for a state of tranquility, suggesting quietness and solitude.

The second formal sentence occurs at lines six and seven. Its subject isn’t clear. Something, probably the totality of all the things that have been noticed – the clover, tree-trunks, new grass, breeze, sound of water lapping and trees –

___________------_____ frames

____________ my crumbled red interior

This is the only ‘difficult’ line in the poem, and also (no pun intended) its heart, in two senses. First, straightforwardly, it’s roughly the middle line of the poem. Second, more interestingly, it moves momentarily from the external environment to the inner life. The red interior suggests the colour of blood and internal organs, perhaps especially the heart. But ‘crumbled’? It does suggest some kind of diseased state, though I don’t know of one that would merit that adjective – some kind of clotting, perhaps, but that would be stretching it. I’m happy to let the word remain suggestive rather than carrying a definite meaning. A heart that isn’t so much broken, perhaps, as dried out and eroded by sorrow.

The next lines take us back to details of the environment: a lake seen through the branches of a tree, or perhaps a branch dipping into the lake, and a nod towards the many lighting effects that a lake can produce: reflection, diffraction, blackness and lightness at the same time.

In the final three lines, the third subject–verb–object sentence, the poem’s speaker is front and centre:

I need to feel the pulse of earth

_______ sleep with the dream of soil

___________------_______ slipping into my nerves

She is reaching for a connection with the land, to have it come alive in her dreams, to heal her crumbling elements. She needs to be, literally, grounded, with a hint, perhaps, in the word ‘dream’, of Indigenous concepts.

Which brings me to the title. There are two possible frayed networks here. Nerves are spoken of as frayed, and as networks. There is also the intricate ecological network of bush beside a lake, and to describe that network as frayed may be to pick up the hint of recent disaster in the frail membranes of grass. More generally, in our times it’s pretty well impossible to think of the natural environment without the effects of climate change coming to mind: all ecological systems are currently under stress. Yet, the poem affirms, the nervous system of a human can the ecological system of the bush can connect – need to connect.

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, where seasonal flowering is happening earlier with each passing year. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land, over which their sovereignty has never been ceded.

* My blogging practice, especially with books of poetry, is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77.