Brian Purcell & Kit Kelen (editors), 100 Poets (Flying Islands 2025)

Most poetry anthologies are implicitly made up of poems that are ‘the best’ in some way or at least the editors’ favourites chosen from a much bigger field of lesser or less loved work. Though the editors of 100 Poets have necessarily been selective, the point here is not that these hundred poems are Winners. Instead, the book is offered as an introduction to a poetic community.

Flying Islands, the brainchild of Kit Kelen, is a non-profit publisher, and a community of poets and readers of poetry. Over the last decade and a half, they have published 100 pocket-sized books of poetry (I’ve read an enjouyed about 20). They have features award-winning poets, grumpy old poets who complain about the lack of recognition elsewhere, and brand new poets flexing their wings. They have included translation, mostly from Chinese to English or vice versa – Kit Kelen is an emeritus professor at Macao University, and Flying Islands has partnered with Macao-based community publisher ASM (the Association of Stories in Macao). They have had a wonderful variety of style, form, tone and subject matter. All of that is represented in 100 Poets.

This book, pocket-sized like the rest, is the hundredth in the series. Each of 100 poets previously published in the series has a single page – a couple of them fit two short poems onto their page, but none take more than a page. Not every notable Australian poet is represented here – there’s no David Malouf, Eileen Chong or John Kinsella, for instance, and not very much from the world of Spoken Word – but it’s hard to imagine a better introduction to the basic ecology of contemporary Australian poetry.

I was going to list the poets from the book who have appeared in this blog. It’s a long list, and not all of them are there because I read their Flying Islands publications. But it would just be a list of names with links. Instead, here is my favourite title, from Tricia Dearborn:

Perimenopause as a pitched battle between the iron supplements and the flooding

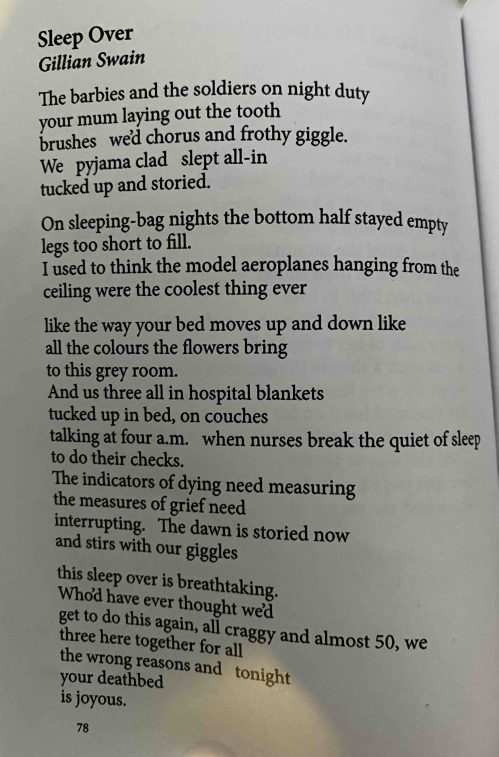

And, in keeping with the blog’s tradition, here’s the poem that appears on page 78, ‘The Sleepover’ by Gillian Swain, whose Flying Islands book is My Skin Its Own Sky (2019):

The first nine lines evoke a pleasant childhood memory. Even if, like me, you never slept over at a friend’s place when you were young, the details – the barbies, the giggling friends brushing their teeth together, the child bodies in adult-sized sleeping bags, the model aeroplanes on the friend’s ceiling – capture brilliantly thrilling combination of intimacy and strangeness that is a sleepover.

Lines 10 and 11 form a finely judged transition from that memory to the very different current situation. They move from the past to the present tense, and the child’s perspective carries over to the different reality – the bed that moves up and down already suggests a hospital, but is presented as a novelty:

like the way your bed moves up and down like

all the colours the flowers bring

And line 12 lands us firmly in the grim present.

to this grey room.

The person addressed in the first lines is now in a hospital bed.

The interplay of benign memory and grim present continues in the rest of the poem: the three friends once again enjoying each other’s presence long into the night. There is giggling again, and stories. The friendship is as alive as ever, but one of the three friends is dying.

The final lines hold this complex emotional reality in a neat paradox. The imminent death of a friend is not trivialised – but nor is the joy of friendship.

the wrong reasons and tonight

your deathbed

is joyous.

The person I have known longest apart from my two sisters died early this year. Our childhood friendhsip wasn’t of the giggling, sleepover variety, but the last time I saw him we did pay more attention to what we enjoyed with and about each other than to what we all knew was coming. The poem resonates strongly for me.

Multiply that by 100 – or to be honest by maybe 75, because not every poem in the book sings to me – and you have quite an experience. I look forward to Flying Islands’ Second 100.

I finished this blog post on the land of Wandandian of the Yuin Nation, whose beaches are said to have the whitest sand on the planet. I acknowledge their Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.