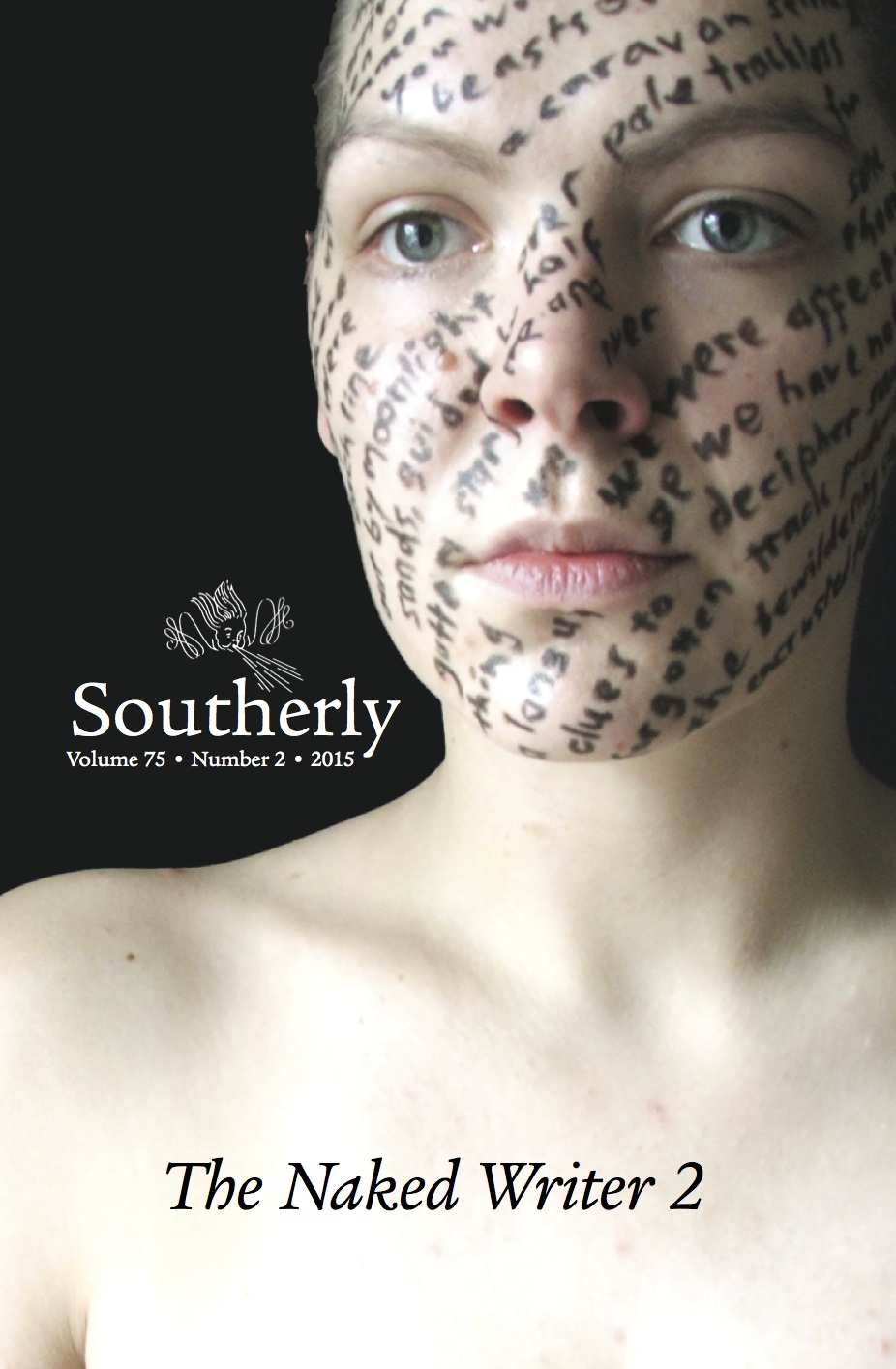

Elizabeth McMahon and David Brooks (editors), Southerly Vol 75 No 2 2015: The Naked Writer 2 (The Journal of the English Association, Sydney, Brandl & Schlesinger)

John Kinsella and Charmaine Papertalk-Green have a collaborative poem in this Southerly. The son of an Anglo-Celtic farmer, Kinsella lived in Geraldton, Western Australia, for the last three years of high school. Papertalk-Green is a Yamaji woman who grew up in nearby Mallewa and now lives just outside Geraldton. The poem – actually a sequence of poems written by the two poets alternately – responds to the works of Western Australian religious architect Monsignor John Hawes as enduring symbols of colonisation.

In what looks like an anxious concern that readers appreciate the significance of the poem, it is embedded in an article by Kinsella, ‘Eclogue Failure or Success: the Collaborative Activism of Poetry’, which among other things spells out the back story, makes learned observations about Virgil’s Eclogues, quotes Wikipedia, throws in a few Greek words, and makes sure we don’t confuse the poem’s first-person elements with the ‘entirely self-interested and subjective’ phenomenon of the selfie. Kinsella is willing to risk being annoyingly self-important if that’s what it takes to ensure that we take him and his collaboration with Papertalk-Green seriously.

Maybe it worked, or maybe the poems would have spoken for themselves, but it’s the kind of project that makes one glad to be alive in the time that it is happening. (Of course, it’s not unique: another stunning example is My Darling Patricia’s 2011 theatrical work, Posts in the Paddock, a collaboration between descendants of Jimmy Governor and descendants of a white family he murdered. That one seems to have sunk without a trace, so maybe all such works do need a John Kinsella to tell us how important they are.)

The challenge of unsparing conversation between Aboriginal peoples and settler Australians is also the subject of Maggie Nolan’s essay ‘Shedding Clothes: Performing cross-cultural exchange through costume and writing in Kim Scott’s That Deadman Dance‘. Apart from calling to mind the pleasure of reading the novel and quoting from it generously, Nolan suggests that, though Bobby/Wabalanginy’s failure to communicate to the colonisers by means of dance may end the book, ‘perhaps his invitation remains open, and Kim Scott, through this novel, is re-extending it to his readers’. I think she’s hit the nail on the head.

There is plenty else here to exercise and delight the mind. In no particular order:

- David Brooks bids an idiosyncratic and clearly deeply felt farewell to his friend the literary critic Veronica Brady, who died last year.

- Fiona McFarlane’s ‘On Reading The Aunt’s Story by Patrick White’, originally a Sydney Ideas lecture, is a warmly intelligent revisiting of that novel.

- Hayley Katzen’s personal essay ‘On Privacy’ rings the changes on the perennial theme of its title, interestingly resonating with John Kinsella’s distinction between the writerly ‘I’ and the facebook or selfie ‘I’, and also with Kim Scott’s meditations on what happens when you write things down.

- Jill Dimond and Helen O’Reilly delve into their respective family histories, the former with an engrossing tale of failed literary aspirations, the latter with the story of the connection between her second cousin Eleanor Dark and poet Christopher Brennan.

- Joe Dolce, whom I should be able to mention without referring to ‘Shuddupaya Face’, interviews the late Dorothy Porter about C P Cavafy and they discuss his poetry’s importance to both of them.

- Of the wide-ranging selection of poems, I particularly enjoyed Alan Gould’s ‘The Epochs Must Go Chatterbox’ and ‘The Insistent Face to Face’, Geoff Page’s genial ‘A Drinking Song for A D Hope’, and Mark Mordue’s Sydney train journey, ‘A Letter for The Emperor’.

- Craig Billingham’s ‘The Final Cast’ reads like a slice of wryly observed Glebe literary life, though its ‘Fiction’ label should spare embarrassment all round.

- Nasrin Mahoutchi’s story of widowerhood, ‘Standing in the Cold’, evokes a bitter Iranian winter with just the right amount of twist at the end.

- In the review section, A J Carruthers discusses Michael Farrell’s Cocky’s Joy and Les Murray’s Waiting for the Past, justifying this unlikely pairing by claiming both poets as ‘experimental’, and arguing that experimental poetry is mainstream in Australia now (and as I write that I realise that the four poems I have singled out above are probably the least ‘experimental’ in this Southerly – ah well, I’m now in my 70th year, so I hope I may be forgiven).

- In The Long Paddock, the journal’s online extension, Jonathan Dunk gives what he describes as a ‘gloves off’ review of Jennifer Maiden’s Drone and Phantoms, and elicits a bare-knuckled response from Maiden. Good on you, Southerly, for putting the conversation out in the open.

I tend to skip the densely scholarly articles (the ones that use words like chronotopic), or at best dip into them. Dipping can come up with some pleasant oddities. In this issue I stumbled on a quote from one Eric Berlatsky to the effect that in some ways ‘the institution of heterosexual marriage is “always already queer”‘. How far we’ve come since William Buckley Junior caused an uproar by calling openly gay Gore Vidal a ‘queer’ on US television in 1968. Now, it seems, in academic parlance, even those ensconced in heterosexual marriages are queer.