Evelyn Araluen and Jonathan Dunk (editors), Overland Nº 256 (Spring 2024)

(Links are to the online versions unless otherwise indicated.)

This is the third of four promised editions of Overland dedicated to commemorating its 70th year. In some ways it marks the end of an era as Toby Fitch, who has been poetry editor for a decade, breaks his silence with ‘A farewell and a poem from poetry editor Toby Fitch, 2015–2025‘, and resigns from the ‘simple work, of carving down a cornucopia of submissions into a small set menu for each issue’.

There is an element of nostalgia in the design and the illustrations reproduced from past issues – by artists including Fred Williams (from 1985), Ian Rankin (from 1987) and Richard Tipping (from 1993). The writing by contrast tends more to the urgent.

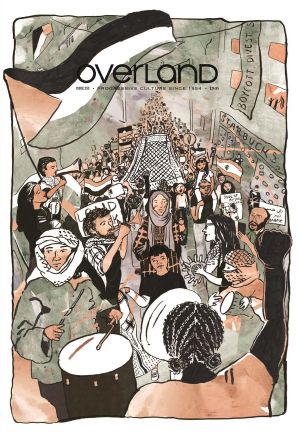

‘Plant hatred in our hearts‘ by Sarah Wehbe, ‘the child of refugees who are the children of refugees’, contextualises the current atrocities in Gaza by listing events reported from there in the first week of the writer’s life. The essay includes this, a reminder of Edward Said’s resonant statement that ‘Palestinians have been denied permission to narrate’:

The recent genocide in Gaza has planted hatred in the hearts of its survivors and onlookers, a painful wound so immense that it will continue to throb generations on. Plant hatred in our hearts and watch as hope and resilience grow in its place. Long after the rubble has settled and the refugees have dispersed across the world, we will share our stories. … We are here, we tell our stories, and as long as that is true, there is hope.

There’s a lot else besides. ‘Dust‘ by Lilli Hayes is a brief, harrowing first-hand account of the impact of asbestos-related mesothelioma on her family. In ‘Résonances‘, Daniel Browning – whose book of essays Close to the Subject won the 2024 Prime Minister’s Literary Award – writes about the work of Swiss–Haitian artist Sasha Huber, as seen through an Australian First Nations lens.

There is more poetry than usual (Toby is going out in a blaze of glory). There are some big names, but I’ll just mention ‘speed, a pastoral‘ by Ruby Connor, which has a subtitle ‘(After John Forbes)‘. It doesn’t feel very Forbes-ish to me, but it captures an episode in a young woman’s life in vivid, unpunctuated three-line stanzas.

My page 78* practice serves me well with this Overland. It falls in the middle of one of the three pieces selected by fiction editor Claire Corbett, the masterly ‘Daryl’s wombat farm‘ by Rowan MacDonald.

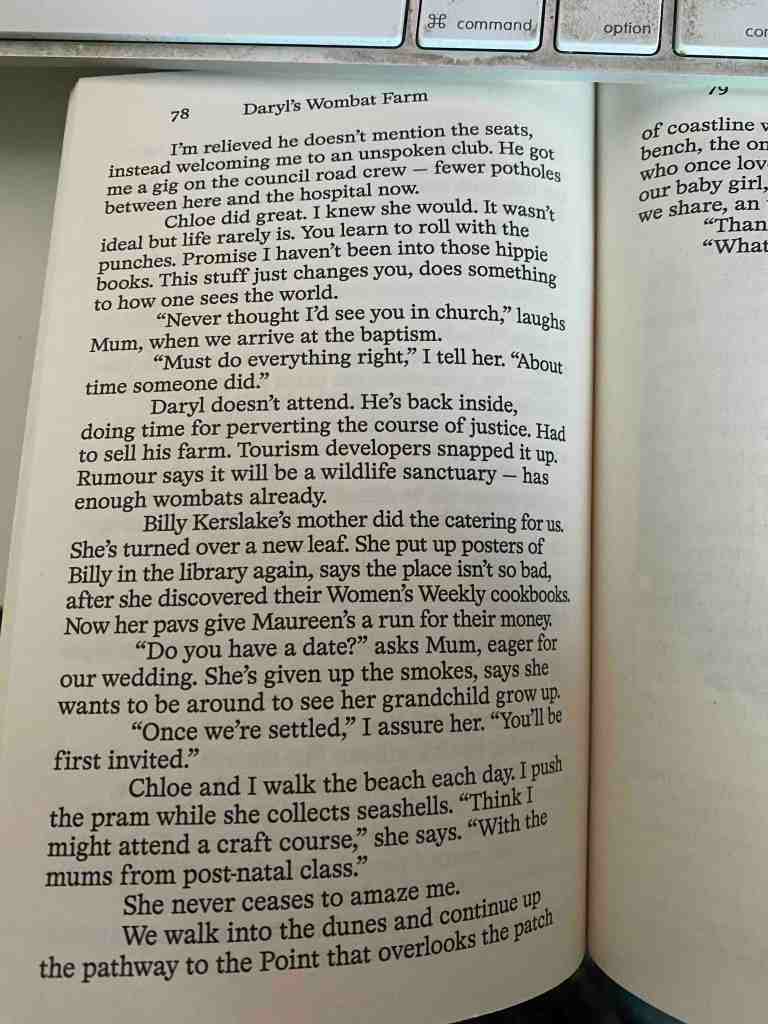

The image gives you an idea of the retro design – the chunky type face and larger font size, and the plain white, matt paper stock. I don’t necessarily prefer this to the modern design, but the larger font is a relief to my ageing eyes, and the poorer paper stock creates a companionable vibe rather than an austerely professional one.

I know I said there’s not much nostalgia in the writing in this Overland. I’ll now contradict myself. This story reminds me solid, social realist, working-class fiction that was a staple of Australian short fiction decades ago. I hasten to add that it does it in a good way.

At the start the narrator, wearing his girlfriend Chloe’s pink gumboots, is shovelling cube-shaped wombat poo. What grows from there is a portrait of a small, marginalised rural community filled with histories of violence, untimely death, ‘unspoken stories’, and a cast of characters who are known only by their first names and vague reference to their status, exploits or fates. Within that portrait is the sweet, elliptically told story of fatherhood.

When I say elliptically-told, I mean it sometimes take a bit of pleasurable work to figure out what’s going on. The beginning of page 78 is an example. The narrator has just returned Curly’s borrowed Skyline (a make of car – my four-year-old grandson would be ashamed of me that I had to look it up) with mess on the seats. Curly, who hasn’t been mentioned previously, doesn’t make a fuss about the mess. Instead he says, ‘Congrats, brother. You’re one of us now.’ Only as the first sentences of page 78 unreel, the reader understands. Curly has played a good role in the narrator’s life in other ways than lending the car, and his ‘one of us’ refers to fatherhood. The narrator has borrowed the car when Chloe was in labour, but didn’t make it to the hospital in time:

I’m relieved he doesn’t mention the seats, instead welcoming me to an unspoken club. He got me a gig on the council road crew — fewer potholes between here and the hospital now.

On the rest of the page, the aftermath of the birth plays out and a number of economically sketched subplots are resolved. The narrator catches himself voicing some of Chloe’s hippie-book-derived philosophy. He has an oblique conversation with his mother about breaking the pattern of neglect and abuse set by his father. Daryl of the wombat farm gets a degree of justice for his role in the narrator’s father’s death. The mother of a missing boy overcomes her dislike of libraries and education enough to put posters back up. Maureen, mentioned once before in connection with pavs, gets another mention. A wedding is mooted. And there’s a tiny, beautifully pitched conversation about the future.

Chloe did great. I knew she would. It wasn’t ideal but life rarely is. You learn to roll with the punches. Promise I haven’t been into those hippie books. This stuff just changes you, does something to how one sees the world.

Never thought I’d see you in church,’ laughs Mum, when we arrive at the baptism.

‘Must do everything right,’ I tell her. ‘About time someone did.’

Daryl doesn’t attend. He’s back inside, doing time for perverting the course of justice. Had to sell his farm. Tourism developers snapped it up. Rumour says it will be a wildlife sanctuary – has enough wombats already.

Billy Kerslake’s mother did the catering for us. She’s turned over a new leaf. She put up posters of Billy in the library again, says the place isn’t so bad, after she discovered their Women’s Weekly cookbooks. Now her pavs give Maureen’s a run for their money.

‘Do you have a date?’ asks Mum, eager for our wedding. She’s given up the smokes, says she wants to be around to see her grandchild grow up.

‘Once we’re settled,’ I assure her. ‘You’ll be first invited.’

Chloe and I walk the beach each day. I push the pram while she collects seashells. ‘Think I might attend a craft course,’ she says. ‘With the mums from post-natal class.’

She never ceases to amaze me.

The story could end there, really, but it continues for another 75 words, and concludes on an explicitly optimistic note that sings:

We hold our baby girl, smile in awe at this creation, the love we share, an unwritten future ahead.

‘Thank you,’ I say to Chloe.

‘What for?’ she laughs.

It’s a story that repays the closer attention that my page 78 practice requires.

I wrote this blog post on the land of the Wangal and Gadigal clans of the Eora nation. I gratefully acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for this beautiful country for millennia, and lived through extraordinary changes in the land and climate over that time.

* My blogging practice is focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age, currently page 78.