Helen Garner, Chloe Hooper & Sarah Krasnostein, The Mushroom Tapes: Conversations on a triple murder trial (Black Ink 2025)

A couple of years ago, in an attempt to limit the way this blog ate into my time, I decided that when I was writing about a book, I would focus arbitrarily on the page that corresponded to my age. No attempt at a proper review, no selection of the most quotable bits, just a look at one page.

It didn’t work out to be a time-saver. As often as not, the discussion of page 77, then page 78, became an added extra to a general discussion of the book.

I hereby resolve to stick rigorously to page 78 (and soon to page 79), and assume that my readers can go elsewhere for proper, thoughtful reviews.

The Mushroom Tapes is a good book to start my new policy. Few Australians won’t know about Erin Patterson’s trial last year for murder involving a Beef Wellington made with deadly mushrooms served up to her in-laws. If you really know nothing about it, here’s a Wikipedia link. Almost as few readers won’t know who Helen Garner, Chloe Hooper and Sarah Krasnostein are. (I’ve linked their names to lists of my blog posts where they appear.)

This book was originally conceived as a podcast in which three writers who have covered criminal trials chatted about this one. The podcast came to nothing, and they made a book from the tapes. I come close to being its ideal reader because I managed to pay very little attention to the trial as it was happening, so I didn’t come to it suffering from mushroom-overload.

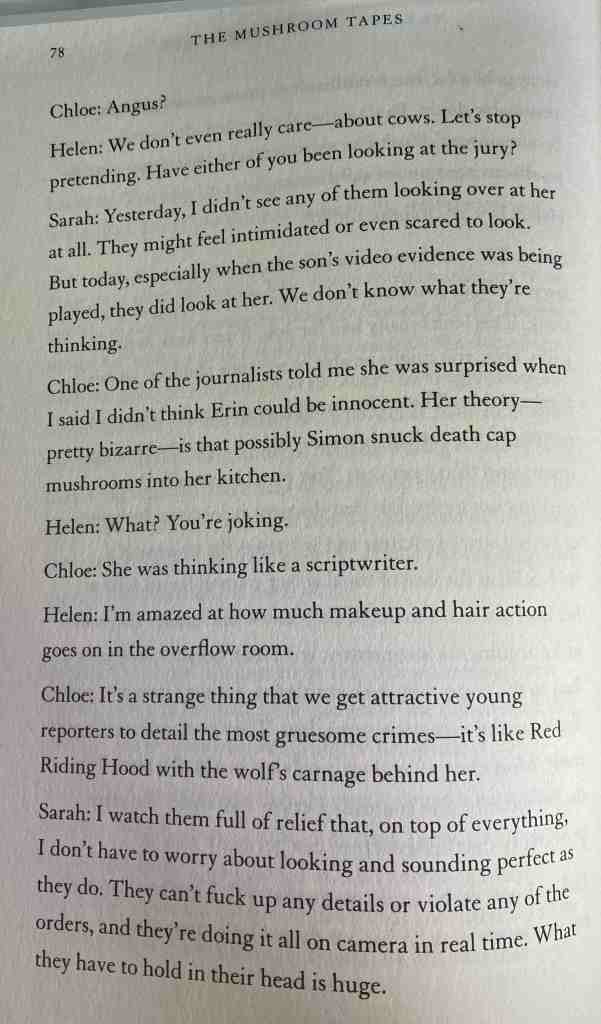

Page 78 is one of the pages that records the writers/tapers’ conversation while driving around. It occurs in Part II, ‘The Church and the House’. They have visited the church where Erin Patterson and her in-laws worshipped, and then her house. Sarah Krasnostein, the only one among them who is an actual lawyer, has just given a little lecture about the pros and cons of a guilty plea. Helen, always the one to draw attention to details of the environment, has asked what some black cattle all spread out on a hill ‘in a lovely way’ are called. Chloe has a stab at an answer:

It turns out the page gives a good sense of the flavour of the conversations generally. There’s not a lot of rambling. Having raised the subject of the cows, Helen abruptly shuts it down: ‘We don’t even really care – about cows!’ And they’re away trading insights and observations – about the jury, and for most of this page about the journalists following the case.

Sarah’s comment on the jury is the kind of thing that all three of the women contribute. They don’t all manage to get into the courtroom at every session, so each of them has a brief to observe as fully and acutely as they can and report back. What emerges is a number of verbal sketches of Erin Patterson herself in the dock, and of other players – jury member, witnesses, lawyers, and perhaps especially Ian Wilkinson, the Pattersons’ pastor sitting in dignified silence in the back row. Sarah’s comment on this page, ‘We don’t know what they’re thinking,’ is again typical. Though they occasionally agonise over whether they are just a part of the media circus / witch hunt that surrounds the case, and though much of the book feels like chat among friends, at heart these are three serious observers. None of them wanted to take on the slog and heartache of writing a book about the case, but each of them takes her role as witness seriously. As this page exemplifies, all three bring feminist perspectives to the task: here they are talking about the lot of young female journalists, but elsewhere they also bring an unsettling degree of sympathy to a woman who would kill her in-laws.

People who still see Helen Garner as the ogre who was mean about younger women in The First Stone (some of the most vocal of whom haven’t actually read the book ‘on principle’) might find fuel for their fires here: her astonishment at a journalist’s ingenious theory of Erin Patterson’s innocence pretty much leaps off the page, and she expresses amazement at the ‘makeup and hair action’ among the young women journalists. (On page 79, she sticks to her guns: ‘Everybody should smile less, especially women, in public. Every advertisement or commercial is full of people smiling with unnatural vehemence, and it drives me insane.’) I read this grumpiness less as critical of the young woman than decrying the pressure on them to look the part.

Chloe, a couple of decades younger than curmudgeonly Helen, is more sympathetic. She sees the young woman’s theory as bizarre, but recognises the story-telling impulse: ‘She’s thinking like a script-writer.’ Mind you, her image of the attractive young reporters as being ‘like Red Riding Hood with the wolf’s carnage behind her’ shows that she also has a script-writer’s eye. (Which is the kind of thing that makes this book very readable.)

Sarah, who may be a decade or so younger than Chloe, has even less distance. I don’t want to say that she’s humourless, but she tends to be the one who supplies facts in the conversation: facts about the law, and also for instance about toxic mushrooms. Here she reminds the others, and us, of the exigencies of the young female journalists’ worklives. (I remember hearing somewhere that a female television journalist’s hair is an important tool of her trade.) On the top of the next page, it’s Chloe who amplifies the point: ‘Whereas the male crime-journalists look grizzled and broken.’

That’s it. So much more to say about the book. You can read about it all over the place.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge their Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.