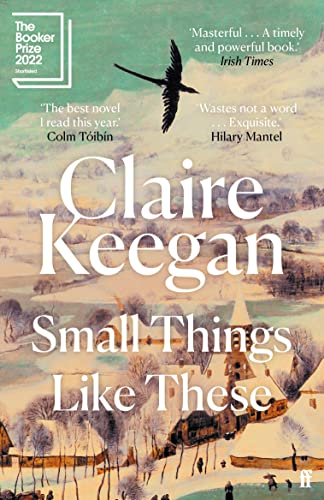

Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These (Faber & Faber 2021)

I first became aware of Claire Keegan through The Quiet Girl (An Cailín Ciúin), an Irish-language film based on her short story ‘Foster’. I saw the film at the 2022 Sydney Film Festival, and was blown away by its portrayal of a small girl’s escape from a terrible situation. The final moment, which I won’t describe because of spoilerphobia except to say that a single, ambiguous word is spoken, is one of the most powerfully moving I’ve seen. The acting (especially Catherine Clinch as the girl), the cinematography (Kate McCullough), the direction (Colm Bairéad) and the script (by Colm Bairéad, closely following Claire Keegan’s prose) are all brilliant. I still haven’t read ‘Foster’ but I was delighted to be given Small Things Like These on Father’s Day.

It’s a tiny book – just 117 pages. It’s set in a small Irish village. Its action takes place over a few days in late December in the time not so long ago when the Catholic Church dominated the lives of most Irish people. Bill Furlong, the coal and timber merchant, is being run off his feet in the pre-Christmas rush. The son of an unmarried woman, he and his mother were able to thrive in spite of the stigma thanks to the patronage of a wealthy Protestant woman – a situation that has uncanny echoes in the Thrity Umrigar books The Space Between Us (which I’m currently reading) and The Secrets Between Us (my blog post here). He is devoted to his wife and five daughters.

A shadow is cast over this benign scene by two pages that precede the beginning of the text proper. First there is the dedication: ‘to the women and children who suffered time in Ireland’s mother and baby homes and Magdalen laundries’. Then, on a page to itself, there is an excerpt from The Proclamation of the Irish Republic, 1916, which declares that the republic resolves, among other things, to cherish ‘all of the children of the nation equally’. Having a rough knowledge of the Magdalen laundries (Wikipedia entry here if you need to look it up), I was prepared for a little book of horrors.

Claire Keegan is a finer writer than that. There is horror, but not the jump-scare, demon-rising-from-the-grave kind, or even the Hanya Yanagihara A Little Life kind. Just outside the village there’s a ‘training school’ for girls of low character and an associated laundry, which ‘had a good reputation’. When Bill delivers a load of coal there on Christmas Eve, he comes upon a young woman who is obviously being abused, and he isn’t reassured by the nuns’ attempts to, well, gaslight him. It’s a small village, and the whispers say that no one can challenge the Church. Aware that his own mother could have found herself in the young woman’s situation, Bill faces a dilemma.

So the book hinges on a small chance encounter, a small crisis of conscience for an ordinary man, who many would say is leading a small life. The title can be read as the beginning of a sentence: Small things like these … pose big moral challenges / … can change the way you see the world / … can disrupt oppressive institutions / …

This blog generally looks at page 76. I might have preferred to talk about the page when Bill sits down to a cup of tea with the Mother Superior, or one of the pages where the abused girl talks to him. But page 76, it turns out, illustrates beautifully the way Claire Keegan tells her story.

It occurs at about the three-quarter point. We have been told very little of what’s happening in Bill’s mind. He doesn’t talk about what he has seen. Perhaps he can’t – he’s a working class Irishman of his era. But his wife, Eileen, can tell he’s ‘out of sorts’. The family go to Mass on Christmas morning. Bill stays back near the door when Eileen and their daughters walk down the aisle and slide into a pew, ‘as they’d been taught’. We’re not told if Bill usually stays by the door, or if this is a sign of new alienation. What follows could easily be a simple description of Irish villagers arriving for Mass in a past era (not all that dissimilar to Mass in the North Queensland town where I was a child in the 1950s):

Some women with headscarves were saying the rosary under their breath, their thumbs worrying through the beads. Members of big farming families and business people passed by in wool and tweed, wafts of soap and perfume, striding up to the front and letting down the hinges of the kneelers. Older men slipped in, taking their caps off and making the sign of the cross, deftly, with a finger. A young, freshly married man walked red-faced to sit with his new wife in the middle of the chapel. Gossipers stayed down on the edge of the aisle to get a good gawk, watching for a new jacket or haircut, a limp, anything out of the ordinary. When Doherty the vet passed by with his arm in a sling, there was some elbowing and whispers then more when the postmistress who’d had the triplets passed by wearing a green, velvet hat. Small children were given keys to play with, to amuse themselves, and soothers. A baby was taken out, sobbing in heaves, struggling to get loose from his mother’s hold.

This may feel like an exercise in nostalgia. But it’s not like, for example, the moment in Robert Dessaix’s Arabesques where he ‘realises’ that the lives of simple Portuguese women at Mass ‘had been redeemed, not by understanding, not by seeing Truth face to Face, but by being gathered up into the Church’ (my blog post here). Neither Bill Furlong not Claire Keegan, observing this gathering, projects visions of redemption onto it. This is an insider’s view. We are told people’s names. We can guess why the freshly-married man is red-faced, we recognise that different people make the sign of the cross differently (I love ‘deftly, with a finger’), there are class differences, children and babies need to be dealt with. It’s a picture of a community coming together that anyone of a certain age with an Irish-influenced Catholic childhood will recognise.

But it’s a critical insider’s view. Bill has a fresh distance because of his moral dilemma, Claire and the reader have perspective created by the seismic shifts in Irish culture since the time of the novel. This is a picture of a surveillance state, benign enough you’d think, but any small divergence from the normal – a sling, a new hat – is noted. It’s characteristic of Keegan’s writing that none of the divergences noted by the gossipers has any moral weight attached to it – we’re left to imagine for ourselves how that would go. We haven’t been told in so many words (this isn’t a Hollywood movie, after all) that Bill is mulling over what to do or not do, but as he looks over this scene, we feel with him the coercive pressure to conform, to accept the authority of the Church, not to rock the boat. The baby, ‘sobbing in heaves’, has to be removed – his mother’s hold is unescapable. Small things like these accumulate so that we understand the pressure Bill faces.

The whole book is a marvel.

After Howard’s End was published, E M Forster began another novel named Arctic Summer, but never finished it. Damon Galgut has co-opted the title for this novel about Forster, appropriately enough given that the book is suffused with a sense of unfulfilled desire and unachieved goals.

After Howard’s End was published, E M Forster began another novel named Arctic Summer, but never finished it. Damon Galgut has co-opted the title for this novel about Forster, appropriately enough given that the book is suffused with a sense of unfulfilled desire and unachieved goals.