Adrian Tomine, Killing and Dying (Faber & Faber 2015)

Recently in my favourite bookshop a customer asked if they had any comics. The person behind the counter replied in a tone that reminded me of one of the sterner nuns from my childhood, ‘We don’t have comics. We do have some graphic novels.’ Maybe I’m just meeting snobbery with pedantry, but if a novel is an extended work of fiction, then Killing and Dying isn’t one. Nor is Joe Sacco’s Palestine or Art Spigelman’s Maus. If those works of sequential art, which aren’t novels but which surely meet the criteria of respectability implied by that bookseller’s tone, can’t be called ‘comics’, what can we call them? I’m sticking with ‘comics’.

Recently in my favourite bookshop a customer asked if they had any comics. The person behind the counter replied in a tone that reminded me of one of the sterner nuns from my childhood, ‘We don’t have comics. We do have some graphic novels.’ Maybe I’m just meeting snobbery with pedantry, but if a novel is an extended work of fiction, then Killing and Dying isn’t one. Nor is Joe Sacco’s Palestine or Art Spigelman’s Maus. If those works of sequential art, which aren’t novels but which surely meet the criteria of respectability implied by that bookseller’s tone, can’t be called ‘comics’, what can we call them? I’m sticking with ‘comics’.

Killing and Dying is an excellent comic, comprising six short stories. The first story, ‘A Brief History of the Art Form Known as “Hortisculpture”‘, is a laugh-out-loud tragedy of frustrated artistic ambition. The protagonist of the second, ‘Amber Sweet’, discovers that she is a dead ringer for a famous porn star, which explains why men have been relating to her oddly. ‘Go Owls’ is a longer story about an initially hopeful relationship between two recovering alcoholics. In the title story, the teenaged protagonist has her heart set on becoming a stand-up comedian, while a whole other story plays out in the images, only elliptically referred to in the text. (The title, by the way, is to be read literally but also as in the world of entertainment.) These four stories are told in a progression of almost completely uniform small frames, only some of them in colour, creating a sense of laidback confidence: no need for visual fireworks, this story will hold the reader. And indeed it does – with extraordinary art that conceals art, each of these stories unfolds seamlessly. They may be comics but they’re quality story-telling.

The other two stories, ‘Translated, from the Japanese’ and ‘Intruders’, apart from being interesting for themselves, serve to demonstrate that Tomine is capable of different visual effects. The former has the same neat figures and impeccable lettering, but uses larger frames of varying dimensions, as befits an illustrated version of what turns out to be a letter written by a Japanese woman to her infant son, to be read much later, perhaps after her death. The latter has a rougher graphic style, a complete departure from the contained precision of the rest of the book, which matches the simmering violence of the situation.

It’s no surprise that Adrian Tomine’s work appears in the New Yorker, including a number of covers. Not that I see the New Yorker very often, but his stories have the understated economy, the decorum, the sharp wit and the slightly downbeat wryness one associates with that venerable institution.

I will probably write more about

I will probably write more about

I read this book as an act of solidarity with The Emerging Artist. Thanks to a year-long series of lunchtime lecture–slideshows given by an art enthusiast in the French Department in my undergraduate years, I had a general idea of the history of Western art up to Picasso, so I could engage intelligently as she tackled assignments on Rembrandt or Watteau, but when she needed a sounding board on anything postmodern, I didn’t even know when to nod interestedly. She said she found Steve Shipps helpful.

I read this book as an act of solidarity with The Emerging Artist. Thanks to a year-long series of lunchtime lecture–slideshows given by an art enthusiast in the French Department in my undergraduate years, I had a general idea of the history of Western art up to Picasso, so I could engage intelligently as she tackled assignments on Rembrandt or Watteau, but when she needed a sounding board on anything postmodern, I didn’t even know when to nod interestedly. She said she found Steve Shipps helpful.

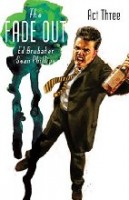

There’s a lot of old Hollywood anti-Communism around just now. On Thursday night I saw Jay Roach’s Trumbo at the movies. On Friday night we had a family birthday outing to the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! On Saturday I read this birthday-present comic, the final ‘Act’ ofFade Out. All three deal with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s attack on Hollywood writers in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

There’s a lot of old Hollywood anti-Communism around just now. On Thursday night I saw Jay Roach’s Trumbo at the movies. On Friday night we had a family birthday outing to the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! On Saturday I read this birthday-present comic, the final ‘Act’ ofFade Out. All three deal with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s attack on Hollywood writers in the late 1940s and early 1950s.