My Saturday morning was topped off with a session at noon, then one in the late afternoon.

12 pm: The Wood and the Trees (I’ll add a link to the podcast when/if it is released.)

This was a chat among three non-fiction writers who are passionate about the environment, and especially trees: Sophie Cunningham (This Devastating Fever, City of Trees), Inga Simpson (Where the Trees Were and Understory) and Ashley Hay (Gum). Aashley Hay was there as facilitator and said very little about her own work, though Inga Simpson at one stage acnowledged her as an important influence on her own writing.

The conversation ranged widely over the science and poetry of trees, trees as intimate companions and as culturally significant beings, trees under threat from climate change and capitalist rapacity. Forest bathing was mentioned, but not explained.

Ashley Hay kicked the session off by asking each of the others for her first memory of trees. Their answers were terrific, but I confess that the main effect of the question was to send me ricocheting off to memories of my own: there are at least a dozen individual trees that were important to me as a child, ranging from the solitary pawpaw tree that grew right next to our verandah to the guava tree in the far cow paddock that I felt was my own personal discovery. I did pay attention to what the writers were saying, but what I took from the session was this powerful blast of nostalgia.

There is currently a hunger for information and thinking about trees, we were told, and for trees themselves, perhaps because the climate crisis is threatening them. A list of recent books emerged. I guess I share that hunger as I’ve read at least some of the books. Honourable mention went to Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (link to my blog post), Suzanne Zimard’s Finding the Mother Tree (on my TBR shelf), and Richard Powers’ The Overstory (my blog post again). And there’s Sophie Cunningham’s instagram account Sophie’s Tree of the Day, which I would definitely be following if I used Instagram. And the same goes for US poet Ada Limón’s ‘You Are Here‘ project.

The Nutmeg’s Curse by the superb writer Amitav Ghosh was quoted. Leonard Woolf was a tree enthusiast, and one of Virginia’s last diary entries was about his trees. We were told about the miraculous survivor trees of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

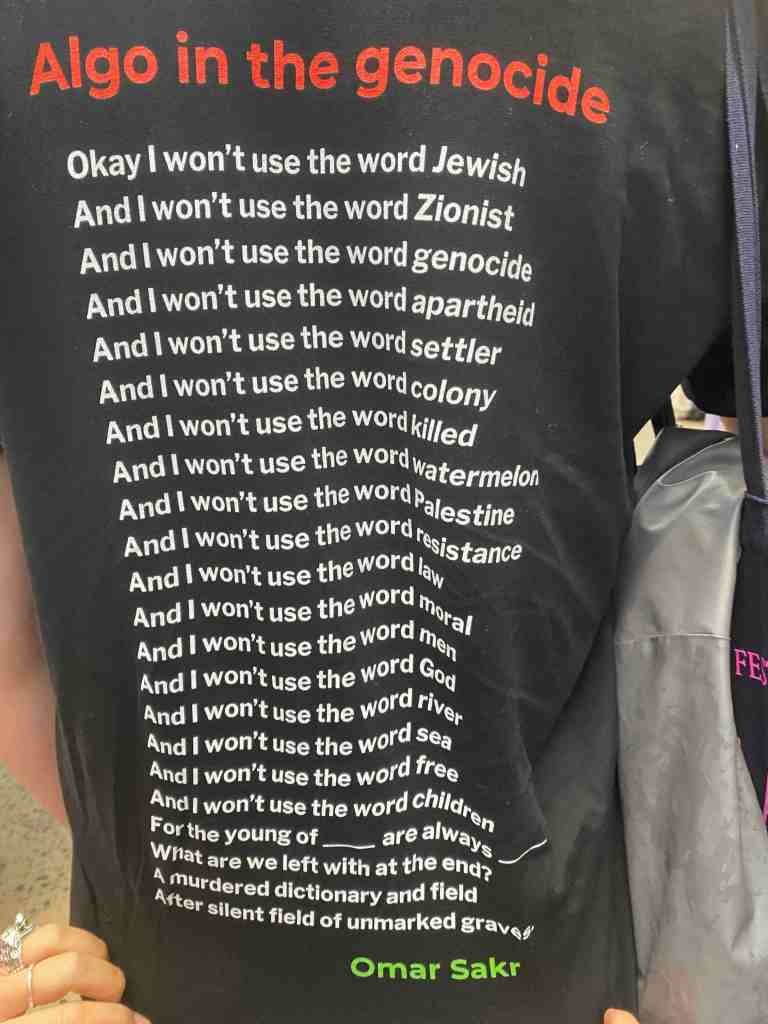

The session ended with someone – I think it was Ashley Hay – reading us the Adrienne Rich poem ‘What Kind of Times are These?’ You can read the whole poem at this link. Here’s the last stanza, rich with implication about why this was an important session to have at a writers’ festival in 2025:

And I won't tell you where it is, so why do I tell you

anything? Because you still listen, because in times like these

to have you listen at all, it's necessary

to talk about trees.

I was reluctant to go out again after a couple of hours in the comfort of home. But duty called, and I dragged myself up the hill to attend possibly the only solo poetry reading of the festival, the only African heritage person to top a bill. It turned out to be THE BEST EVENT OF THE FESTIVAL:

4.30 pm Lemn Sissay: Let the Light Pour In

After a disembodied voice acknowledged that we were on Gadigal land, Lemn Sissay burst onto the stage in a mustard yellow suit to a huge burst of applause – evidently the room was filled with fans, some of whom may have attended workshops he had led earlier. He made a physically huge show of lapping up the applause, and his energy didn’t sag for the whole hour.

What to say about what followed? He began with a comment that any event is open to a number of interpretations – and told us of a moment when another festival guest had assumed he was a taxi driver. Now you might take some meaning out of that, he said (Sissay is Black), but maybe he was just waiting for a taxi. Then, moving on, having raised and disowned the racism interpretation, he muttered cheerfully, ‘I hate him anyway.’

The first poem he performed is a long narrative, ‘Mourning Breaks’, which was accompanied by projections of dramatic stylised drawings. Disarmingly, he stopped after a couple of stanzas – ‘I’m not happy with doing it like that’ – and started over. It’s a gruelling poem in which a man hangs from a branch on the face of a cliff, refusing to let go. Sissay has uploaded a performance, without the images, at this link – if you watch it, stay to the end because it’s got a killer last line.

As we were recovering, he did some fabulous comedy about poetry readings: If you came here with a friend, and were thinking, ‘How much more of this do I have to sit through?’, if you were thinking, ‘I know a bit about poetry readings, and he should have started with something light to warm us up,’ if you came with a friend and were thinking, ‘This relationship is doomed,’ …. all I can say is, ‘I’m sorry.’

The rest of the session focused on his most recent book, Let the Light Pour In (Canongate Books 2023). He has written about trauma, he told us, including a play adaptation of Benjamin Zephaniah’s novel Refugee Boy, and work about his own difficult childhood growing up in care. But this is not a book about trauma. For 13 years, he wrote a poem every morning – they had to have four lines, and the second and fourth had to rhyme. Many of them were crap. This book contains the best of them, and he read us some wonderful ones, interspersed with chat that was a brilliant illustration of the line from Terry Pratchett quoted in an earlier session: ‘The opposite of funny isn’t serious, the opposite of funny is not-funny.’ Lemn Sissay was very funny, and also very serious.

He showed us a photo of one of his short poems taking up the whole of a man’s arm. He showed us the website of a marriage celebrant who featured one of his poems (‘Invisible kisses’, a kind of response to Kipling’s ‘If’). He asked if anyone in the audience had used that poem at their wedding. One person had. He then said he was suing all those people. (In response to a question at the end of the reading, he reassured us that of course he wasn’t suing anyone, and spoke interestingly about the way the internet and AI are changing the nature of copyright and intellectual property.)

Some poems he tossed off. Some, especially one that went right over our heads, he carefully explained (it was a joke poem that hinged on spelling of ‘yacht’). Some he lingered over, performed a number of times to allow them to settle in. One of those, he said, he wrote for young mothers who gave their babies up for adoption (not, he said, ‘abandoned’ but heroically gave the babies a chance of a better life):

Remember you were loved

I felt your spirit grow

I held on for the love of you

And then for love let go

Then, he told us, a friend of his asked him to read this poem at her wife’s funeral – the poem took on a whole other meaning, still profoundly moving. ‘All poetry,’ he said more than once, ‘is an emotional witness statement.’ He also said, ‘There is no one way to do a poetry reading.’ He could have added, ‘There’s no one way to be a survivor of care, a University Chancellor, a literary prize judge, an OBE.’

The Sydney Writers’ Festival is happening on Gadigal land. I have written this blog post on Gadigal and Wangal land. I acknowledge their Elders past present and emerging. It’s still raining.