László Krasznahorkai, The Melancholy of Resistance (1989, translated by George Szirtes, published by Tuskar Rocks Press 2000)

Before the meeting: László Krasznahorkai won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Melancholy of Resistance (Hungarian title Az ellenállás melankóliája) was his second novel. Written as the Communist regime was collapsing in Hungary in 1989, it centres around an outbreak of senseless mass violence in a small Hungarian town. In real life, happily, the transition from Communism to a version of democracy was peaceful, but the book’s nightmarish vision and weird allegorical tale resonate far beyond its immediate political context.

One thing was clear to me as I read: this book, with its absence of paragraph breaks, long internal monologues about, for example, esoteric musicology, a key character who remains unseen and unheard except for weird chirping sounds, and many story lines that peter out or are resolved with a throwaway comment in the middle of something else, could never be made into a film. I was wrong. In 2000 (the year this translation was published), Béla Tarr adapted it in Werckmeister Harmonies, which has been called ‘one of the major achievements of twenty-first-century cinema’ (an impressive accolade, even if it was written in the YouTube comments section).

I haven’t seen the film, but I can’t think of a better way to convey the feel of the book than to show you its trailer:

There you have it: the young, naive idealist who may well be the idiot people think he is; the old, disillusioned musicologist; the corpse of a huge whale wheeled into town; the ominously silent crowds of men; the awful mob violence; the invading military (though I don’t remember a helicopter in the book). Some elements are missing, though I expect they’re in the movie itself: a mysterious character known as the Prince, two children caught in the crossfire, and the key roles of two women. Nor do the streets of the movie seem quite as covered in frozen garbage as those of the novel.

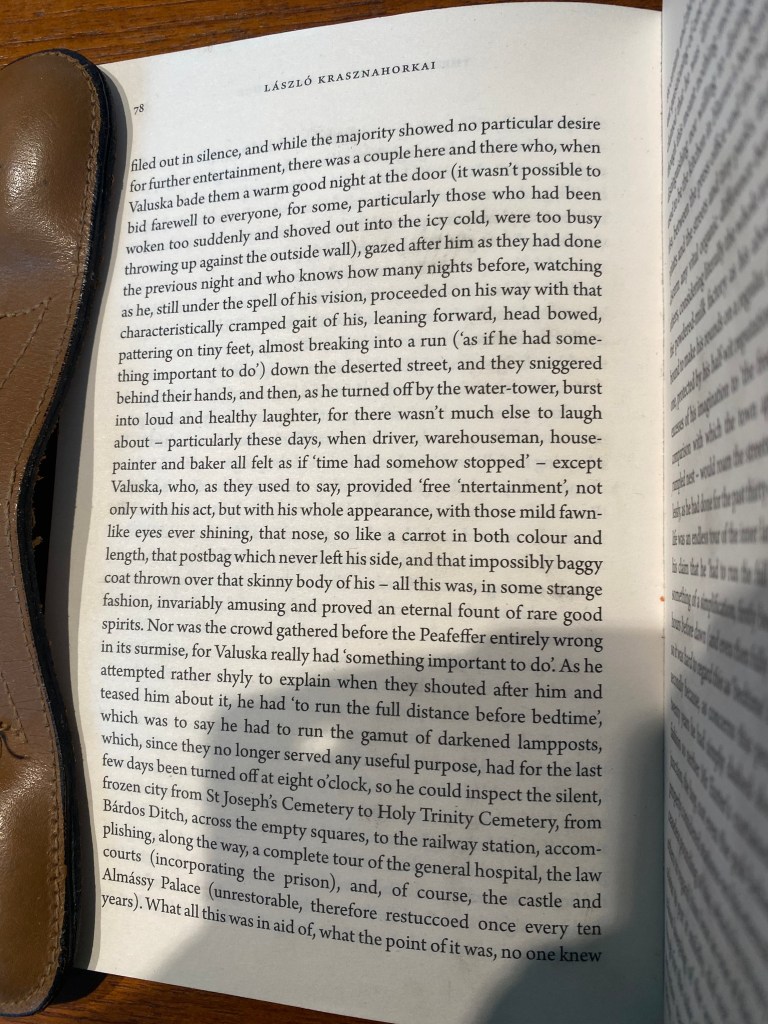

The book’s most striking feature is absence of paragraph breaks and the predominance of long sentences. The sight of page after page of uninterrupted text is intimidating at first, and it’s annoying having to hunt around if you lose your place, but the effect on the page, as I imagine it is on the screen, is a dreamlike flow. And George Szirtes’ has translated the Hungarian into extraordinarily smooth English that enhances that effect. This isn’t Proust, where the sentences turn in on themselves, clauses nesting within clauses, with a hypnotic, introspective effect. Here the effect is more propulsive – the long sentences sweep you on. And they work brilliantly in a book where characters are always in motion (even if sometimes the motion is mental). They walk, stumble, run errands, occasionally waddle, stalk, pursue, flee, but always move.

It’s as if the characters can’t stop for breath, so the text has to hold out for as long as it can without a full stop, and even longer for a bit of white space.

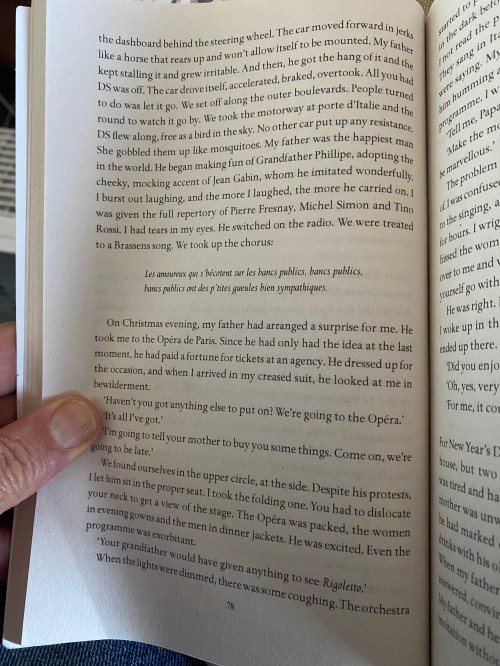

Page 78* occurs partway through the third paragraph/section, which unfolds from the point of view of Valuska, a kind of holy idiot and easily the book’s most sympathetic character. Valuska has been introduced doing his nightly routine at closing time in the Peafeffer tavern, in which he demonstrates the mechanics of a solar eclipse, deploying three paralytic drunks to represent the sun, the moon and the earth. His attempt to communicate the awe-inspiring order of the cosmos is tolerated by the drinkers as a way to delay closing time. At the top of this page, the evening is over and they walk out into the cold night:

The first thing to note about this page is that, counting the sentence that started on the previous page, there are just three sentences. The middle one is quite short: at 20 words it may be the shortest in the book, but is otherwise unremarkable. The others are typical of the book.

It would please my inner 11-year old Queenslander to analyse one of them – identify the main clause and the subsidiary clauses, and the nature of the subsidiary clauses. It probably wouldn’t be very entertaining for my readers, so I’ll limit myself to noting that the basic structure of this:

So they filed out in silence, and while the majority showed no particular desire for further entertainment, there was a couple here and there who, when Valuska bade them a warm good night at the door (it wasn’t possible to bid farewell to everyone, for some, particularly those who had been woken too suddenly and shoved out into the icy cold, were too busy throwing up against the outside wall), gazed after him as they had done the previous night and who knows how many nights before watching as he, still under the spell of his vision, proceeded on his way with that characteristically cramped gait of his, leaning forward, head bowed, puttering on tiny feet, almost breaking into a run (‘as if he had something important to do’) down the deserted street, and they sniggered behind their hands, and then, as he turned of by the water-tower, burst into loud and healthy laughter, for there wasn’t much else to laugh about – particularly these days, when driver, warehouseman, house-painter and baker all felt as if ‘time had somehow stopped’ – except Valuska, who, as they used to say, provided ‘free ’ntertainment’, not only with his act, but with his whole appearance, with those mild fawn-like eyes ever shining, that nose, so like a carrot in both colour and length, that postbag which never left his side, and that impossibly baggy coat thrown over that skinny body of his – all this was, in some strange fashion, invariably amusing and proved an eternal fount of rare good spirits

is five linked principal clauses:

So they filed out, and a couple gazed after him, and they sniggered, and then burst into laughter, for there wasn’t much else to laugh about.

That skeleton is adorned with images of the bitter cold, vaguely comic drinkers throwing up, descriptions of Valuska, an explanation of what they found amusing about him, and a reminder of the drinkers’ wider context – ‘driver, warehouseman, house painter and baker’.

Valuska stands out: time has ‘somehow stopped’ for the town in general, but he is fascinated by the continuous movement of the heavenly bodies and is himself always on the move. That stopped-ness comes into focus in chilling scenes in which the town square is full of motionless men, all as if waiting for something. And when they move, the effect is shocking, violent.

I don’t know that I’d recommend the book, but I enjoyed it, and it has stayed hauntingly in my mind. It makes many other books feel like plodding reportage.

After the meeting: This was one of the best meetings of the book group ever. We exchanged gifts – everyone was supposed to bring a book from their shelves, though the book I received (a Gary Disher title) is in suspiciously mint condition. Some of us read poems – by Adrian Mitchell, Mary Oliver, Simon Armitage and Robert Gray. We reminisced about the group’s history and argued about how firmly fixed our list of dates for the year should be. We shared stories of courage and shame. We ate well. We enjoyed the early summer evening. And we had a wonderfully animated discussion of the book.

Three out of eight of us had read the whole thing. A number of others were well under way and intend to finish it. Everyone had something to say. Here are some of my highlights.

I was reading Mrs Dalloway a couple of pages a day alongside of The Melancholy of Resistance, and felt strongly that the books spoke to each other but couldn’t say how. When someone mentioned the way the narrative focus transfers from one character to the next at the end of each section, I realised this is one of the similarities: where Virginia Woolf’s narrator slips from one character’s mind to another sometimes several times on a single page, Krasznahorkai’s narrator does a similar thing, but on a much wider arc.

One man read the book not realising it was more than 30 years old, and the political dimensions of it seemed right up to date. I don’t know if he mentioned the MAGA riots in January 2020, but they certainly seemed relevant.

Someone said it was hard to resist a book where a character spends four pages trying to work out the physics of hammering a nail while repeatedly hitting himself on the thumb. And then, having solved the problem by acting without thinking about it, he is told by his cleaning lady that he’s done it all wrong. Our group member who has been studying philosophy told us that this is even funnier when you know that one of Heidegger’s most famous passages involves a hammer. (That person’s favourite moment is Mr Eszter’s seemingly interminable rumination about the pointlessness of the diatonic scale (at least that’s what I think it’s about) – which was my second least favourite moment.)

Contrary to my own response, one man felt the book was intensely cinematic. And as we talked it was clear that it’s full of memorable scenes. We reminded each other of the scene where Valuska demonstrates the mechanics of an eclipse, the interrogation scene, the force with which Mrs Eszter’s hand comes down on Valuska’s shoulder to stop him from speaking, the horriific scene where the mob runs riot in the hospital, the brilliantly evoked streets full of frozen garbage, and more.

At heart, one man said, it’s a love story between Mr Eszter, an intellectual who has given up any hope that thinking could be of value, and naive, well-meaning Valuska.

And that’s a wrap for the Book Group for 2025.

The Book Group met on Gadigal land, and I have written this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present of those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.