The young woman who was my neighbour at the launch of Ritual was just at the festival for the one day. She said she planned to go to ‘all the Palestinian sessions’. My next two sessions would have been on her radar.

Peter Beinart is a New York journalist, commentator, substacker, and professor of journalism and political science. He was in conversation with ABC journalist Debbie Whitmont.

He began by saying that he hoped there would be people in the packed room who disagreed with him. If there were any such, he made no attempt to placate them, but left us in no doubt about his views. He spoke fast (and at times furious), so please don’t take this as a summary of his whole presentation, but here are some things I jotted down.

The Jewish community in the USA and elsewhere is painfully divided over current events in Israel-Palestine. He begins his book Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza with a letter to a former friend: speaking from a position of love and Jewish solidarity, he says that something has gone horribly wrong, that the current action of Israel is a profound desecration, the greatest spiritual crisis of Judaism since the Holocaust.

There has been a great sustaining story for Jews. They are the world’s perpetual victims. In line with that narrative, Hamas’s horrific attacks on 7 October 2023 are seen in the context of the Holocaust and, before that, the centuries of pogroms and persecution. But placing the attacks in that narrative is to dehumanise Palestinians. To understand 7 October we need to look to different analogies – the example he gave was of a group of Native Americans who broke out of virtual imprisonment to perform a horrific massacre. In the case of 7 October, the Israeli Jews weren’t a marginalised group – it was horrible that they were killed but they were members of the oppressing group.

The narrative behind the creation of Israel is that Jews need a safe place. But supremacy does not make you safe. In South Africa it was widely believed that the relinquishment of white supremacy and Apartheid would lead to a bloodbath because whites would no longer be protected from the armed resistance. It didn’t happen(whatever the current president of the USA might say). Similar fears in Northern Ireland proved to be illusory. When structures of supremacy were taken down, the violence pretty much ended.

Yet the fear persists. Jewish Israelis fear to visit Gaza or the West Bank – while going to hospitals where there are many Palestinians among the doctors and nurses. Rather than argue, one needs to ask, ‘What are the experiences that led you to that belief?’

The answer is partly that the Holocaust is not ancient history. There are still fewer Jews in the world than there were in 1939. He is not suggesting that we should forget the past, but it matter what stories we tell. In his early 30s he went (as a journalist, I think) to spend time with Palestinians on the West Bank. Nothing in his life had prepared him for the brutality and terror he witnessed there. He realised then that the story of the persecution of the Jews was not the only story, and not the main one to tell in Israel-Palestine.

Among some circles there is a new definition of what it means to be a Jew. To be a real Jew, you must unconditionally support Israel. This, he says as an observant Jew, is a form of idolatry – the worship of something human-made. States are meant to support their citizens. Under this new definition, the state of Israel is to be worshipped: it’s not a relationship of support but of adoration. Likewise there’s a new definition of antisemitism that includes anti-Zionism: this would mean that any support of Palestinians is antisemitic. Again he quoted Edward Said, ‘Palestinians have been denied permission to narrate.’ This would make that denial absolute.

In fact, Jews are disproportionately represented in pro-Palestinian activities in the USA. These are not ‘self-hating’ Jews, but Jews acting in keeping with longstanding cultural values.

The last sentence of my notes: ‘Jews need to be liberated from supremacy.’

Plestia Alaqad is a young Palestinian woman who has defied the lack of permission named by Edward Said. On 6 October 2023, a recent graduate, her application for a job with a news outlet in Gaza was rejected: local journalists weren’t needed. On 9 October, after the Hamas attack on Israel and the beginning of Israel’s response, she received a call saying things had changed. So she began an astonishing period of reporting. (At least, this is what I gathered from this conversation; the Wikipedia page tells a slightly different story.) For six weeks, she published first-person eye-witness accounts as Israel’s attacks on Gaza became more intense. She also published her diary on Instagram, giving millions of followers what Wikipedia calls ‘an unfiltered glimpse into the harrowing realities of life under siege’. And she wrote poetry. Her book, Eyes of Gaza, is a memoir built from her Instagram diaries.

At the beginning of the session, Sarah Saleh stepped onto the stage and sat beneath the huge screen to tell us who Plestia Alaqad was. Being completely ignorant, I assumed Plestia Alaqad was about to be beamed in from the Middle East, like Ittay Flescher and Raja Shehadeh. In fact, she is currently living in Australia, having left Gaza in November 2023 in fear for her family’s safety. Sara was alone on the stage so her guest could make an entrance: our applause was accepted, not by a stereotypically dour, hijab-wearing Palestinian refugee, but by a glamorous, vivacious, long-haired young woman.

The entrance wasn’t just a nice piece of theatre. Like Flescher and Shehadeh, she sees her work as being in large part to counter the dehumanisation of Palestinians – and she made us see her as human. This is why she writes about shopping as well as the outright horrors. ‘People don’t expect to see me shopping. They want to donate clothes to me.’

‘I knew how to be a journalist,’ she said, ‘but not how to be a journalist in the middle of a genocide.’

‘You have to deal with the genocide,’ she said, ‘and then you have to deal with the media’s treatment of it.’ Once she had come to public notice, mainstream journalist wanted to hear from her. She told us of one interview, with an Israeli news outlet I thnk, where the interviewer kept asking her leading questions, wanting her to say something like, ‘Kill all Jews.’ But this is not her position, and she referred constantly to the perpetrators of atrocities specifically as the IDF, not even ‘the Israelis’ in general. The interview was not published.

Children in Gaza grow up afraid of the sky.

About her book, she said, ‘I want people of the future to not believe that this book is non-fiction.’

It was a hard transition from Plestia Alaqad to the formalities of the festival’s closing address. The CEO Brooke Webb (wearing a Protect the Dolls t-shirt), Artistic Director Ann Mossop and the NSW Minister for the Arts John Graham each spoke in justifiably self-congratulatory mode. What remains tantalisingly in my memory from all three speeches is an unexplained image of Jeanette Winterson being pursued by three stage managers. Apparently it was funny and made sense, but I guess you had to be there.

Anna Funder’s speech was terrific. The bears of its title came from an incident in her childhood. At a campsite in a Claifornian redwood forest, she needed to go to the toilet. Her mother, who was breastfeeding little Anna’s baby sister, told her to go to the toilet block by herself. When she came back and said she couldn’t go alone because, ‘There’s a bear down there,’ her mother, like the mother in Margaret Mahy’s classic children’s book, A Lion in the Meadow (it’s me, not Anna Funder, making that comparison), told her to stop making things up. The third time little Anna came back she was accompanied by a burly man who wanted to know who kept sending this small child to the toilet block when there was a bear there.

She went on to offer a range of perspectives on that story. Her mother told it often as a humorous story against herself as a neglectful mother. It could be read as showing the importance of the kindness of strangers. And so on.

I’m writing this at least ten days after the event, from very scanty and mostly unreadable notes, but where the story landed in the end was to make an analogy with the work of a writer, to go to places where there are bears – in Anna Funder’s case, the world of secret police, patriarchy, and like that. In these days, with the advent of AI under a global surveillance oligarchy, we need to recognise the importance of human beings writing and reading, daring to go where the robots cannot.

For the podcast of this address, clink on the title above. [Added later: An edited version was published in the July 2025 issue of the Monthly.]

And that’s it for another year, bar the events scheduled outside the week in May and of course the podcast series (I’ll add links to them as they appear). The Festival had an official blogger, Dylin Hardcastle. You can read his blogs at this link.

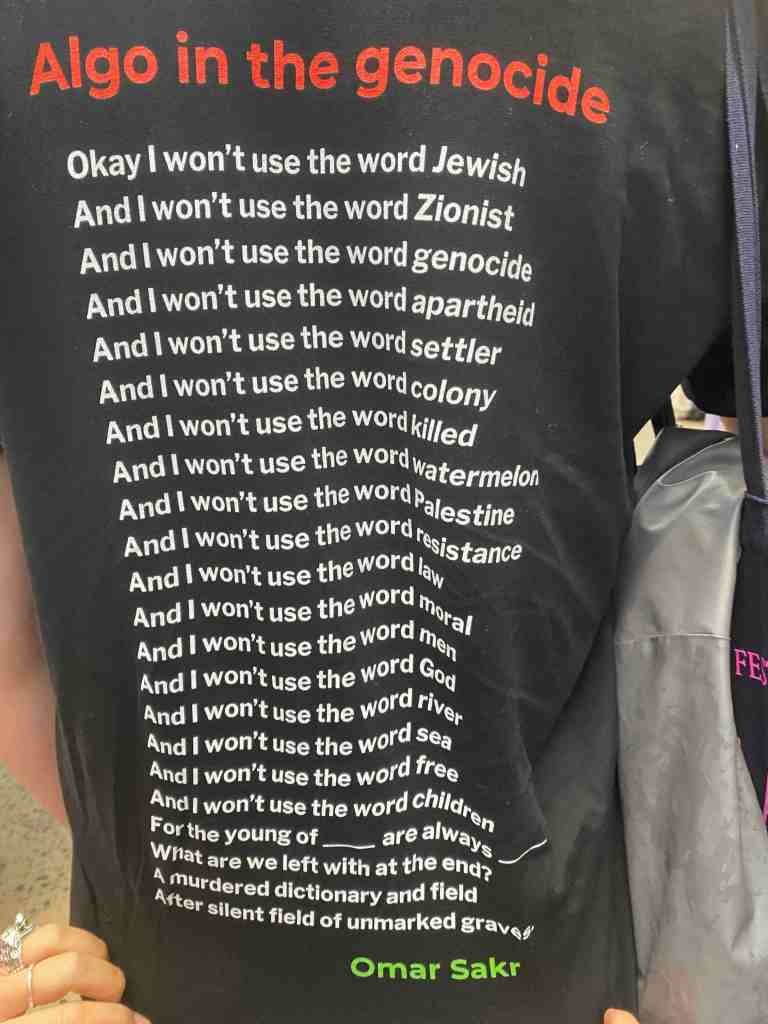

The small fraction of the Festival that I saw was terrific. At least four people, from different perspectives, spoke of the importance of countering the dehumanisation of Palestinians. There were lots of Readers against Genocide t-shirts, but any fears that there would be displays of antisemitism proved to be unfounded. There were wonderful poetry events – curated as part of the First Nations program, featuring a spectacular international guest, launching a landmark anthology of Muslim poets. I missed the intimate poetry sessions that were a feature of the Festival when it was held at the Walsh Bay wharves. Maybe next year we could have Pádraig Ó Tuama, or Judith Beveridge, or Eileen Chong, or a swag of poets from Flying Islands, Australian Poetry, or Red Room.

I gained new insights into books I’d read, and was tantalised about books I hadn’t. I’ve come away with a swag from Gleebooks, and have added to my already vast To Be Read shelf. I’ve already read a book by Raja Shehadeh from the Newtown library and am part way through a book by Emily Maguire.

Normal blogging will resume shortly.

The Sydney Writers’ Festival took place on Gadigal land. I have written this post on Gadigal and Wangal land, where the days are growing shorter and colder beneath, at this moment, a cloudless sky. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging and warmly welcome any First nations readers of this blog.