Before the meeting: Mary Roy (1933–2022) was an extraordinary woman. She successfully challenged an inheritance law in the Indian state of Kerala so that women were able to inherit property, and she founded a ground-breaking school. That school, Pallikoodam, has a photo of her on its home page, accompanied by a vision statement:

Pallikoodam is born of the vision of Mrs Mary Roy. For fifty plus years she worked on moulding an extraordinary school that imparts a creative and all-round education that produces happy, confident children, aware of their talents as well as their limitations, unafraid of pursuing their dreams and living life to its fullest. Today, every one of us in Pallikoodam works to realise and forge ahead with her dream.

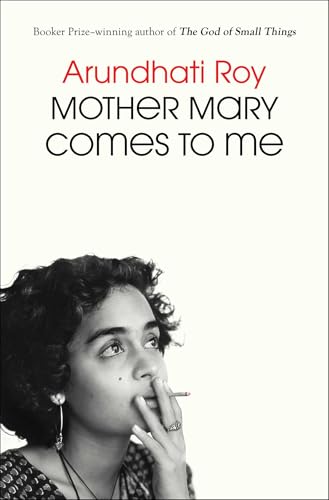

Mary Roy was also the mother of writer Arundhati Roy. In this memoir, she emerges as a formidable woman who did brilliant things, earning the admiration and cult-like devotion of many while challenging patriarchal institutions, and was at the same time a tyrannical, unpredictable, terrifyingly self-centred mother. Near the end of the book, Arundhati Roy describes a moment in 2022 when she was having dinner with three male friends, including her close friend Sanjay. She received a message on her phone:

It was from my mother. They, all men, each of them, including Sanjay, beloved by their besotted mothers, must have noticed the blood drain from my face and wondered what had happened. How could I explain to them that what had scared me was that I had got a message from my mother saying that she loved me.

It says a lot that readers understand perfectly why the message is terrifying, and that we also understand the intense moral, emotional and intellectual complexities involved in Roy sending a positive reply.

I love this book. It’s the story of the intertwined lives of two brilliant women, with the last half century of Indian history as an often intrusive backdrop. The genesis of Arundhati Roy’s writing is vividly told: her two novels The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, as well as her non-fiction, ‘activist’ writing, opposing the construction of a big dam that would displace millions of people, exposing the suffering of the people of Kashmir, reporting on time spent in a jungle with communist (‘Naxalite’) guerrillas, opposing Narendra Modi’s regime, and more.

I can imagine the book being portrayed as a misery memoir in which a famous writer complains about her wretched childhood, or as an exposé of a monster generally regarded as a saint. But that would be to misrepresent it. Mrs Roy’s personality was no secret. Her most loyal adherents were aware of her rages, her indulgences (she was always accompanied by an attendant bearing her asthma medication and, later in life, a supply of jujubes). And though Arundhati and her brother suffered terribly at their mother’s hands, she was a powerful force for good in their lives. There are any number of quotable lines to illustrate this complexity. Here’s just one from page 61, when the daughter was fifteen years old:

Between her bouts of rage and increasing physical violence, Mrs Roy told her daughter that if she put her mind to it, she could be anything she wanted to be. To her daughter those words were a life raft that tided her over pitch-darkness, wild currents and a deadly undertow.

There’s so much to enjoy. Arundhati has a friendship with the legendary John Berger, which gives us the unforgettable image of him as an elephant fanning her with his flapping ears. Hollywood actor John Cusack makes a cameo appearance as a witness of the mother–daughter relationship.

A look at page 78* makes it clear that the book is at least as much about the ‘me’ of the song as it is about ‘Mother Mary’. Young Arundhati is at the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture, free for the first time of Mrs Roy’s overwhelming presence. She has re-encountered the young man she calls JC – her first meeting with him when she was nearly fifteen and he was nineteen had been the first time she understood what sexual desire was: ‘My brain, my heart, my soul – all parked themselves in my groin.’ Back then, she had tried to be invisible. But on page 77, he tells her that he had thought she was a beautiful girl:

I was delighted. I had never, not for half of half a second, thought of myself as beautiful. <snip> I was the opposite of what Syrian Christian girls were meant to be. I was thin and dark and risky.

Such is the power of the writing that one hardly stops to question how the stunningly beauty the young Arundhati Roy that we see in photos could ever have felt that way.

On page 78 – after a paragraph about the Delhi family connection, Mrs Joseph, who disapproves of her – Arundhati is still absorbing that first delight:

So, it was nice to be thought of as beautiful, even if it was the opinion of a minority of one.

The rest of the page evokes grungy student life at the School of Planning and Architecture in new Delhi.

Laurie Baker (Wikipedia page here) is named as standing for the opposite of what was taught at the school. He was a pioneer of sustainable, organic architecture who designed Mrs Roy’s Pallikoodam school. He had inspired Arundhati to veer away from her earliest ambition, to be a writer, and leave home to study architecture. Though Arundhati did go on to be a writer, it was at the School of Planning and Architecture that some of her most important, enduring relationships were formed. As much as anything else the book celebrates these friendships.

After the meeting: Everyone loved this book and we loved discussing it. Someone threw a small grenade, saying that she didn’t see that Mrs Roy was such a terrible parent, that really Arundhati Roy had unfairly demonised her. The catalogue of physical and emotional violence, the fact that Arundhati’s brother shared her view, the way independent witnesses described Mrs Roy as ‘your mad mother’ and laughed at the terror on Arundhati’s face when she had to deal with her: none of this made a dent in her view. We could agree that Arundhati didn’t stay victim – she saw her mother as a model of being powerful in the world, and eventually came to recognise that in her way she loved her, and had given her the wherewithal to build a big life for herself, even if that meant rebelling against her.

We all learned things. For some it was about Indian politics, in particular about Karachi. For all of us, the impact of winning the Booker Prize was a revelation. We all had our ignorance about the Syrian Christians of India slightly decreased (the Roys are Syrian Christians – in Modi’s India, not Indian enough).

We read and discussed the book along with Kiran Desai’s The Loneleiness of Sonia and Sunny. Both books feature complex mother-daughter relationships, both have rich insights into the cultural and political relationships between India and the West, a number of historical events feature in both. But no one was much interested in a compare-and-contrast discussions.

Because it’s November*, I will now burst into rhyme:

November verse 4: Student days

Are student days always anarchic,

smoke-filled, garbage-racked, insane,

angry at the hierarchic

lectures that would tame the brain

with wisdom that's received as certain?

Always the time that lifts the burden

from the backs of those who bear

the yoke of old beliefs? Time where

new songs are sung and new words spoken,

daughters, sons beyond command

(don’t even try to understand),

first loves formed and hearts first broken,

new ways found with fork and knife,

friendships made that last for life?

The group met on the land of Gadigal of the Eora Nation, and I have written this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal. I acknowledge Elders past and present of all those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78, and in November I write fourteen 14-line stanzas in the month. which means incorporating one into most blog posts.