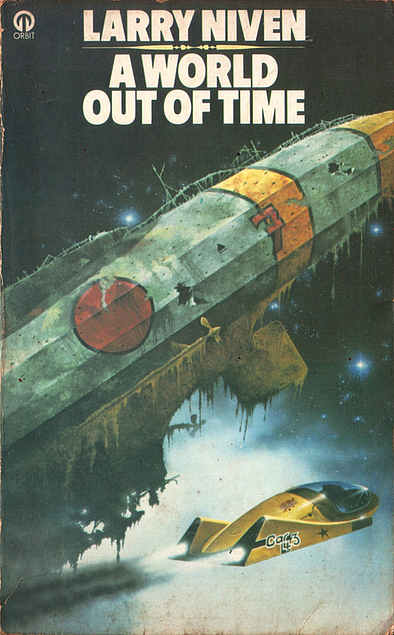

Larry Niven, A World out of Time (©1976, Orbit 1977)

It had been a while since I read something that was just good fun, and I turned to my Spec Fic TBR shelf to fill the lack. This yellowing Bookmooched copy of A World out of Time reminded me of the pleasure of Larry Niven’s Ringworld books, of which pretty much the only thing I remember is that I enjoyed them. It practically leapt into my hands.

And now that I’ve read it I don’t have much to say beyond that it is indeed fun. There are whizz-bang planet-shifting fusion engines; there are sex scenes that would barely raise a vicar’s blush these days but were probably titillating for 14-year-old boy readers in 1977; there are chase scenes, theory about the nature of empires, cool improvised weapons, cute mutated animals, scary mind manipulation, and a plot that’s full of unexpected twists. It’s not ‘hard’ science fiction like Kim Stanley Robinson, or weird like China Miéville, or space opera like Star Wars, but it’s got elements of all of them, and it zips along.

It begins, ‘Once there was a dead man.’ People who opted for cryogenics in the 1970s (‘corpsicles’) are revived as slave labour a couple of centuries later; that is, their personalities are harvested and implanted in the bodies of condemned criminals whose brains have been wiped. Our hero, Corbell, is one of the revived corpsicles. The totalitarian government of the future (‘the State’) assigns him the task of piloting a spacecraft on a round mission that is planned to take hundreds, even thousands of years.

The RNA conditioning that enables him to learn his interstellar pilot craft in a matter of days also modifies his brain so he identifies as a servant of the State. But he manages to rebel and takes off instead to visit the black hole at the centre of the galaxy, where he will almost certainly die, again.

I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to tell you that, with the reluctant help of his State-loyalist computer Peerssa and the wonders of speed-of-light travel, Corbell survives. My arbitrary policy of focusing on page 76 once again bears fruit, as on that page he has just arrived back on a much-changed Earth not thousands of years but roughly three million years into the future. (Maybe one reason I found the book so refreshing is that though the Earth’s temperature is mostly unbearably hot in that distant future, the global heating didn’t happen in the 21st or even the 24th century and wasn’t brought about by anything as mundane as carbon emissions. Ah, the innocence of 1976 future-imaginings!)

On page 76, while Peerssa is orbiting the Earth in their interstellar spacecraft, Corbell has found what looks like a dwelling in a devastated landscape. It made me think of the house at the end of Antonioni’s 1970 movie Zabriskie Point, except this appears to be a single bedroom looking out over the desert. Corbell tells Peerssa that he can’t find a door, and after they decide that it’s unlikely that the roof is meant to lift off or that the entrance is underground:

‘I’ll have to break in,’ he said.

‘Wait. Might the house be equipped with a burglar alarm? I’m not familiar with the design concepts that govern private dwellings. The State built arcologies.’

I had to look up ‘arcology’. It’s a portmanteau word combining ‘architecture’ and ‘ecology’, meaning, according to my phone dictionary, a city built according to a system of architecture that integrates buildings with the natural environment. Peerssa means something slightly different: the State’s arcologies were integrated ecologies of their own, with little attention to the natural environment. I love a book that makes me learn about such concepts.

‘What if it does have a burglar alarm? I’m wearing a helmet. It’ll block most of the sound.’

‘There might be more than bells. Let me attack the house with my message laser.’

‘Will it–?’ Will it reach? Stupid, it was was designed to reach across tens of light-years. ‘Go ahead.’

‘I have the house in view. Firing.’

Looking down on the triangular roof from his post on the roadway, Corbell saw no beam from the sky; but he saw a spot the size of a manhole cover turn red-hot. A patch of earth below the house stirred uneasily; rested; stirred again. Then a ton or so of hillside rose up and spilled away, and a rusted metal object floated out on a whispering air cushion. It was the size of a dishwasher, with a head: a basketball with an eye in it. The head rolled, and a scarlet beam the thickness of Corbell’s arm pierced the clouds.

‘Peerssa, you’re being attacked.’

Peerssa doesn’t have much trouble repelling the attack, and Corbell gets into the house. Though the washing machine plays no further role, both it and the room’s doorlessness foreshadow the kind of challenges Corbell is to face.

This is now the world out of time of the title: apparently deserted, with faint signs of active energy that are almost certainly just machines that have somehow continued to be active long after their human creators and users have died out. The question I had at this point was: ‘If there are no humans left, and the remaining three quarters of the book is to be a Robinson-Crusoe story, how can it stay interesting; and if there are humans, how can they with any degree of plausibility have survived in the devastation that Earth has become?’ At page 76, the real subject of the book is about to become a little more visible: it takes its time showing itself, and when it does, well, it’s fun.