Colleen Z Burke, Cloud Hands (Feakle Press 2024)

Cloud Hands is Colleen Z Burke’s thirteenth book of poetry.

As in those of its forerunners that I’ve read, its typical poem is a short, impressionistic snapshot of landscape, or especially skyscape, mostly in the inner-west Sydney suburb of Newtown. As snapshots, these poems are mostly embedded in a specific moment, a specific circumstance, so we often get a sense of the life of the person taking the shot, and of the broader context.

There are also memories of a working-class childhood. ‘Each Way’, about gambling as part of the family’s way of life, begins, ‘Minor crime was woven / into our lives just like / the salty tang of the sea.’ (I can relate: my own family of origin wasn’t working class, but my farmer father, like Colleen Burke’s, was a patron of illegal SP bookies.)

There are a three poems (‘Illusion’, ‘A nefarious enterprise’ and ‘A magnet’) recalling youthful romance. Colleen’s partner was Declan Affley, the folksinger who accompanies Mick Jagger’s terrible rendition of ‘A Wild Colonial Boy’ in Tony Richardson’s 1970 movie Ned Kelly. Though it is many decades since he left us, he is still a vibrant presence in these poems.

There are people-watching poems, incidents from inner-suburban life, comments on the news, snippets of science and social history. Covid and the bushfires of 2019–2020 loom large. Climate change and environmental degradation threaten to sour the joys of the natural environment.

This is a collection that bears witness to a persistent practice of paying attention – to the world, to history, to life.

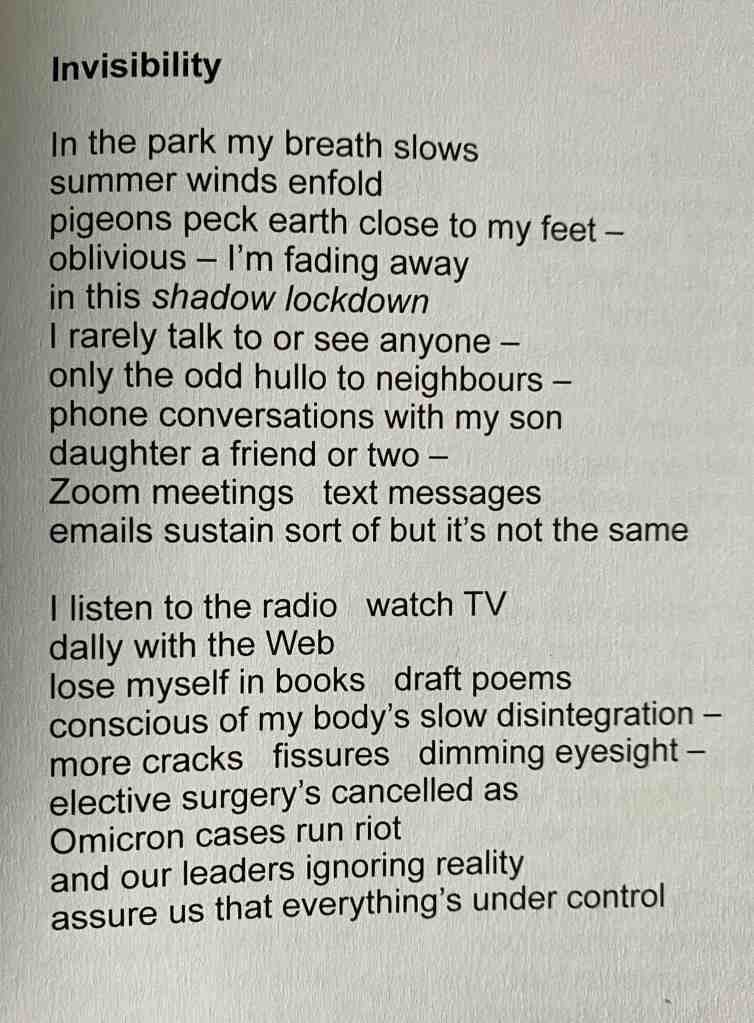

Page 77* is ‘Invisibility’:

Yes, page 77 of the last book I read had a pigeon poem too. But here the pigeons are oblivious rather than chatty, and the despair in the poem is not worn lightly.

This poem is a great example of the value of slow reading. At first quick reading, it’s a straightforward cry of the heart from the dark days of January 2022, when the Omicron variant of Covid was on the rampage in Sydney. In case you need reminding, there were no official restrictions on movement at that time, but Australia had moved from having a remarkably low level of serious illness and death from Covid to having among the highest. The assistance to individuals and businesses from the Federal government had largely dried up, and the Prime Minister of the time was trumpeting a business-as-usual message. Here’s a link to Mike Secombe on that nightmare in The Saturday Paper.

So this poem is, perhaps, an unremarkable record of how one woman suffered in that time: she has minimal contact with other people, she fills her time with solitary activities, and her age-related health issues go unattended to. Like most of us, she finds fault with the Morrison government’s handling of the situation.

That’s all there. But, interestingly, after I started writing this blog post I had a number of conversations that kept sending me back to the poem. One person spoke about a gobsmacking experience using the (I think) Apple Vision Pro goggles – it was as if he was in the room with a musician, could almost touch her. Someone else is reading Naomi Klein’s Doppleganger, and described her account of people involved in the riots of 6 January losing track of the difference between the gaming world and the actual world where there are consequences. Burke’s ‘sort of but it’s not the same’ stops feeling like a banal statement of the obvious and takes on a profound resonance. The poem expresses one woman’s feelings in a specified circumstance, but it sends ripples out well beyond it.

The other thing I noticed as I sat with the poem, or had it sit with me, is the part played by the pigeons. The poem begins, like many of Burke’s poems, with a moment of relaxation in the park – the breeze, pigeons, the earth, her breath slowing down. Then, with the word ‘oblivious’, it turns to the poet’s inner turmoil. The pigeons might have provided a calming anchor, their obliviousness an invitation to pay attention to the present moment. But it was not to be. Skip to the final lines, and the notion of obliviousness returns to round out the poem with ‘our leaders / ignoring reality’. The poem’s speaker is invisible to the pigeons who are engrossed in pecking the earth. She is also invisible to the political leaders who deny that the coronavirus is out of control. The tension between the pigeons’ focus on reality and the political leaders’ wilful ignoring of it is what holds the poem most satisfyingly together.

You can read my blog posts on some of Colleen Z Burke’s previous books here, here, here and here, and on her memoir The Waves Turn here.

I wrote this blog post in Gadigal Wangal country, where I believe Colleen Z Burke also lives. I acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging for their continuing custodianship of this land, over which their sovereignty has never been ceded.

* My blogging practice, especially with books of poetry, is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 77.