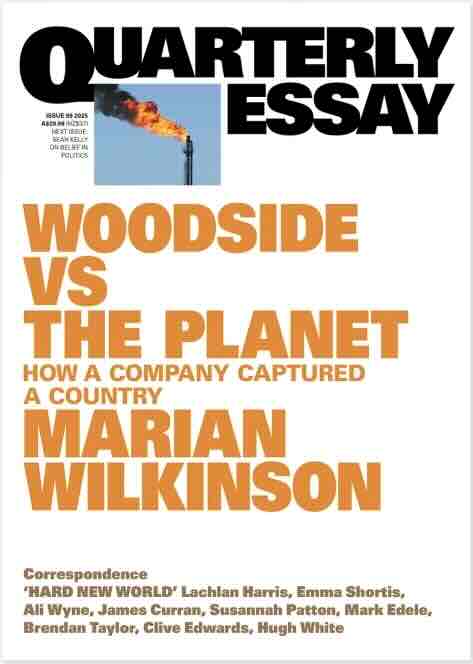

Marian Wilkinson, Woodside vs the Planet: How a Company Captured a Country (Quarterly Essay 99, 2025)

– plus correspondence in Quarterly Essay 100

Marian Wilkinson has a formidable CV as an investigative reporter. This substantial survey of the politics around the activities of Woodside Energy adds one more jewel to her crown.

The essay’s title and subtitle provide an excellent summary. Expanding it slightly: Woodside is expanding its gas extraction and export activities in a way that will contribute to global warming to an alarmingly dangerous extent, and they have gained the wholehearted support for this from successive Western Australian governments and Australian federal governments.

Three things aren’t included in that summary: first, the well organised, courageous and well informed opposition movement; second, the potentially disastrous impact of Woodside’s current and expanding activity on ancient petroglyphs on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia; third, the fact that fossil fuel industries have a limited life ahead of them.

A couple of years ago I visited the standing stones near Évora in Portugal. Our guide said that if the stones were in Spain they would be treated as a national treasure, but in Portugal they remained virtually unprotected in someone’s field. Well, if they were in Australia, and tens of thousands of years older, with infinitely more to tell us about human history, they would be left exposed to whatever pollution fallout might be created by a major industrial site nearby while scientists employed by the responsible corporation argued that there isn’t sufficient evidence of harm.

Marian Wilkinson is a journalist, not an advocate. But she is not in thrall to that concept of balance where you present any situation as a debate between two points of view, with no fact-checking or conclusion. Among the many people she interviewed for the essay is Meg O’Neill, CEO of Woodside, whom she quotes as saying that gas produces less greenhouse effect than coal, and that some gas is necessary as the world transitions to renewable sources of energy. But she doesn’t leave that as one equal side of an argument for and against. What emerges is an understanding that yes, gas will play a role in the transition to renewables, but Woodside and its supporters (or possibly dupes) in government and the media massively overstate how much gas will be needed. The profit motive overrides any concern for the common good.

I came to the essay with a heavy heart. In my mind Woodside was already a climate villain, Western Australia was a state that had been captured by the fossil fuel industry (or was even a virtual branch of it), and Woodside’s impact on the petroglyphs of the Burrup Peninsula was a slow-motion version of the blowing up of the Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto. Nothing in the essay made me change my mind. Instead, it put paid to my lingering hope that the Albanese Labor government would make use of its large majority to face down the mining companies and their allies in the press. And it gave me a much greater understanding of what Wilkinson calls ‘the disruptors’: Disrupt Burrup Hub activists, some Indigenous traditional owners, and more.

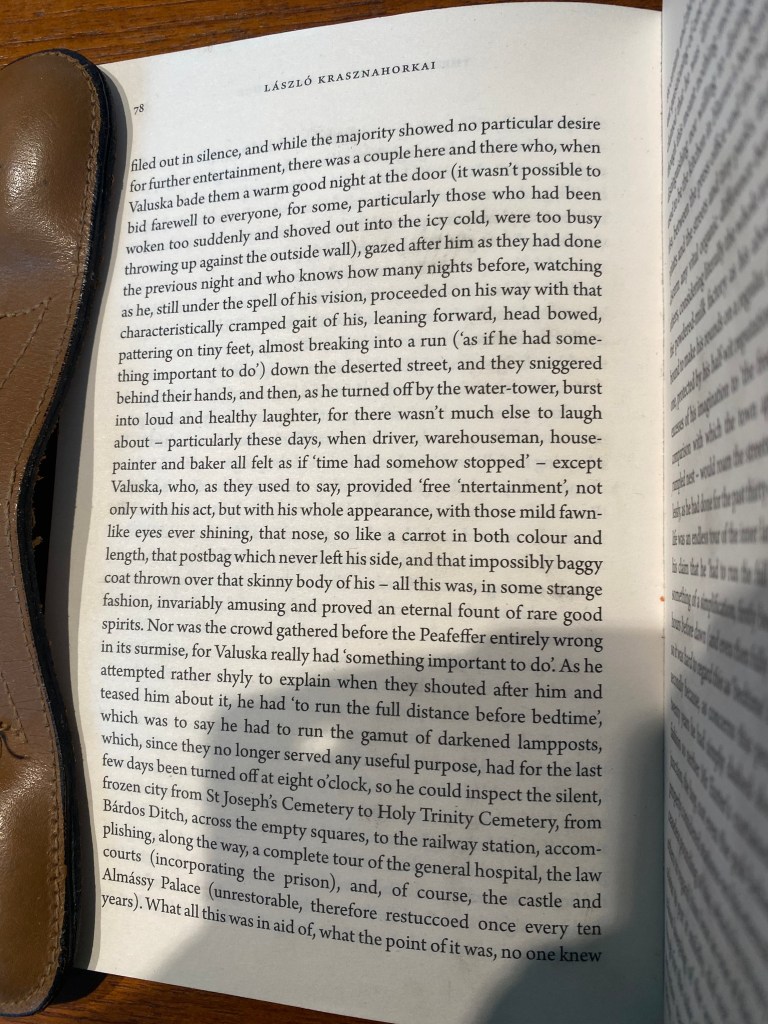

Page 78* is in the eighth and final section of the essay. Earlier sections have dealt with Meg O’Neill’s career, the growth of Woodside, the way Woodside has come to have such tremendous influence on government policy, the disruptors, the struggle over the petroglyphs, and the vision of ‘gas-fired futures’ shared by Woodside and governments. This final section – ‘Woodside in the Age of Accountability’ – introduces an element of hope, and urgency. It lists the tangible results of global warming so far, and quotes eminent scientists as saying that ‘the next three years will be crucial in stopping this seemingly inexorable rising of emissions’. On page 78, the full absurdity of Woodside’s favoured activities come to light:

[Alex Hillman, former Woodside climate adviser turned shareholder activist] said Woodside needs to think about shrinking its gas business, not expanding it. ‘We think it’s a pretty compelling financial case that Woodside should just admit that this fossil-fuel business is going to get smaller and actually celebrate that, because it’s a more valuable strategy.’

Right now, this may sound farfetched, but gas companies like Woodside are under threat. Hillman argues that, globally, oil and gas businesses have made below-market returns and not come close to earning their cost of capital for the past fifteen years. ‘To me that makes it pretty clear that what these companies have been doing isn’t working for investors.’

So even from a purely capitalist perspective, Woodside’s expansion makes no sense. The fact that now the Trump administration is backing a huge Woodside project in mainland USA, as the essay mentions, only underlines that point. Short term gain, long term disaster all round.

Woodside is being hit on two fronts. Not only is more LNG [liquefied natural gas] coming onto the market, but it’s also facing competition from a rising tide of renewables. This year, global investment in the energy transition is set to increase twice as much as investments in oil, gas and coal. This investment is being shaped by what the IEA [International Energy Agency] is calling the ‘Age of Electricity’. The ‘Golden Age of Gas’ that began well over a decade ago is drawing to an end.

China was the world’s biggest LNG importer and Australia’s second-biggest LNG customer in 2023. But China’s prospects as a long-term lucrative coal-to-gas switching customer are in doubt. Instead, its massive investment in renewable energy is disrupting fossil-fuel markets around the world. You can get a striking insight into the scale of China’s renewables revolution by looking at satellite images from NASA’s Earth Observatory of the ‘Solar Great Wall’ in the Kubuqi Desert.

But CEO Meg O’Nell sticks to her guns.

Correspondence in Quarterly Essay 100 (The Good Fight by Sean Kelly) mostly reinforces Wilkinson’s argument. The world is not decarbonising fast enough to avoid dire consequences. Woodside’ activities aren’t helping. Peter Garrett discusses the politics. David Ritter focuses on Scott Reef, an extraordinary marine habitat that is under threat. Shane Watson and Kate Wylie from Doctors for the Environmental Australia describe the difficulties of appealing to existing laws to defend the environment.

Wilkinson says in her response to correspondents that ‘the gulf in thinking between the fossil-fuel industry and the climate movement in Australia was as wide as ever’. I had a brief moment of hope for a robust debate between these two perspectives when I saw that there was a contribution from Glen Gill whose bio says he ‘has over forty years of global experience in the petroleum and electricity industries, including in technical, commercial, regulatory and pubic policy areas’. Sadly, Gill manages to shout a lot. His first paragraphs refer to ‘wild, uninformed statements from activists’, describe the essay as ‘ridiculous’, ‘misleading’ and full of ‘fear, ignorance and hatred’. Marian Wilkinson doesn’t really bother to engage, except to say that the science he claims to rely on is ‘alas not climate science’.

Things are crook, but I’m glad there are people like Marian Wilkinson who are willing to look steadily around them and communicate what they see in clear, uncompromising prose.

I wrote the blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation. I acknowledge Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.