Rod Goodbun and Edwina Shaw (editors), Queersland (AndAlso Press 2025)

Disclosure: Edwina Shaw, co-editor of Queersland, is my niece. The anthology includes a personal essay by her in which I am mentioned, as well as my mother, my brother and other close family members. Members of my extended family make cameo appearances in other essays, with some names changed.

Queersland‘s back cover describes it as made up of ‘stories from queer Queensland writers spanning 80 years of dynamic social histories, as varied as the landscape itself’. True, there is a story of covert male homosexuality during World War Two, a poignant tale of secret love between men in a 1960s country town, and a couple of 21st century pieces dealing with gender-fluidity. But the book’s main subject is the extraordinary flourishing of the queer activism, creativity and community in south-east Queensland under the ‘corrupt, repressive, authoritarian, anti-feminist, anti-queer’ government of Joh Bjelke-Petersen in the 1980s (the adjectives are from ‘Imagine Living in a World …’ by Chantal Eastwell and Karin Cheyne) and the tentative easing of anti-queer laws under his successor as premier, Wayne Goss, in the early 1990s.

Drug-fuelled teenage ‘naughtiness’ on the dance floor, flamboyant costumes, demonstrations, police brutality, the AIDS epidemic, a world of music, intergenerational tensions, First Nations voices, Inkahoots screen-printing company, censorship, the Brisbane Pride Collective, coming-out stories that still feel raw more than 40 years after the event, the Women’s House rape crisis line, intersectionality, tragedy, exhilaration, the growing awareness of gender issues: this is an amazing piece of social history told by a multitude of voices (roughly 40, to be literal) with passion, humour, and above all a sense of community.

A dozen illustrations capture both the flamboyance and the seriousness of the stories. Though I’m a committed lover of books-as-objects, I am sorry this one couldn’t include videos. Several mentions of Lance Leopard sent me searching for the new romantic synthpop band the Megamen – and I found a magnificent, blurred video of ‘Designed for Living‘ from 1983 that makes a beautiful exo-illustration of the book.

I have come to Queersland as a rank outsider. Almost all its cultural references drew blanks with me, and not just the pop music ones. There’s a foreword by Darren Hayes. It’s an elegant and pointed coming-out story, but I couldn’t see why it was featured as a foreword – which I would have seen, of course, if I’d heard of Savage Garden. I know of Kris Kneen, have heard them speak and read reviews of their work, even clapped eyes on them at Brisbane’s Avid Reader bookshop, but ‘Something Other’, the most literary piece in the book, and w-a-a-a-y too much information in any other context, is my introduction to their writing. The other familiar name is Steve MinOn, whose novel First Name Second Name I blogged about recently: his memories of watching a John Travolta movie (Ah, a reference I did recognise!) in Proserpine in ‘Saturday Night Poofta’ confirm my suspicion that the zombie hero of his novel might share some of his own history.

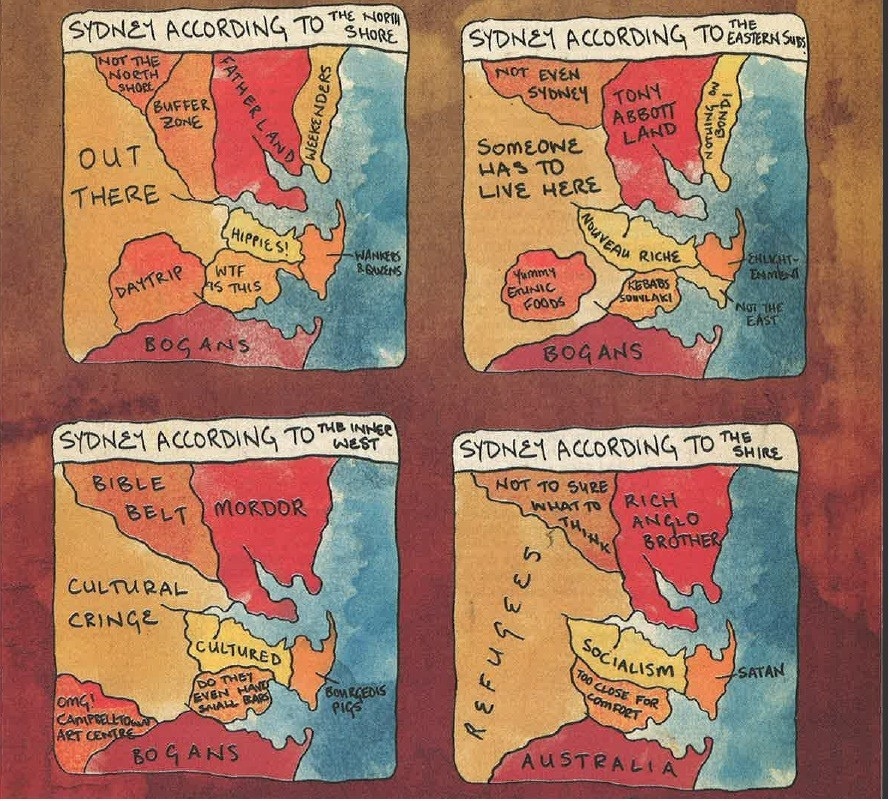

The story of LGBTQI+ communities in Australia often focuses on Sydney and the 1978 Mardi Gras. The Queensland history is just as interesting. This book tells it beautifully.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where I have been privileged to live for decades, though I did live on the outskirts of Meanjin, on Turrbal land, for two years. I acknowledge Elders of those countries past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.