[7 August 2025: I’ve retrieved this post from my old blog because I’m currently reading a book by Geoff Page, and Lawrie & Shirley, reviewed here, is the only other book by him I’ve read since I started blogging]

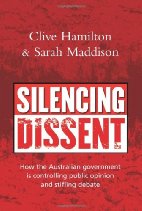

Clive Hamilton & Sarah Maddison, Silencing Dissent (Allen & Unwin 2007)

Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood (1949)

Tim Baker (editor), Waves: great stories from the surf (HarperCollins 2005)

Geoff Page, Lawrie & Shirley: the final cadenza (Pandanus Poetry 2006)

Markus Zusak, The Book Thief (Pan Macmillan Australia 2006)

Leonard Cohen, Book of Longing (Viking 2006)

Heat 13: Harper’s Gold (starting)

Harold Bloom’s Best Poems (continuing)

Gillian Leahy’s movie Our Park has a special place in my heart because the park in question is my local park. But it’s got an even stronger hold on my affections because of its uncomfortable, even gruelling depiction of democracy in action. As they struggle over what use should be made of a little patch of semi-derelict land, people disagree passionately, at times (off camera) come to blows, and (on camera) declare intense animosity for each other. But things are thrashed out. Many points of view are heard. Everyone owns the final result.

That’s not how democracy works in Prime Minister John w Howard’s Australia. People do get beaten up, of course, mostly off camera and with a legal requirement not to talk about it. But disagreement with the government’s policies doesn’t get much of a look-in. Silencing Dissent is a chilling look at the way dissenting voices have been systematically intimidated, bribed, excluded, marginalised or drowned out over the last decade or so. It lists the democratic institutions that have been undermined: the media, the senate, non-government organisations, intelligence and defence services, the public service, universities. Because it’s a book of essays all making the same point, there’s quite a bit of overlap and repetition, but for slow learners like me that’s all to the good. A young friend of mine is fond of saying that the Coalition are Fascists (he intends the term precisely) and that only cowardice stops people from saying so; the detail accumulated in this book makes him seem less hyperbolic.

To cheer myself up I moved on to a bit of fiction by Flannery O’Connor. I hope that sentence doesn’t make her turn in her grave, but paradoxically there is something cheering about Wise Blood. It reads to me as if it was written in a trance – as if some twisted angel had dictated it and the young Ms O’Connor just wrote it down, trusting it would amount to something. Most of its characters are all ‘a little bit off their heads’ and some are a big bit off the rails. Hazel Motes, played by Brad Dourif in the John Huston movie which I plan to watch again on DVD soon, is in obsessive revolt against the punitive and repressive Christianity of his childhood, and burns with an evangelical imperative to preach a Church of Christ without Christ (I would have said cacangelical but the word doesn’t seem to exist).

I remember reading a review of the movie that compared Hazel to the Monty Python character who was trying to train ravens to fly underwater. That comparison captures the bleak comedy of the book, but leaves out the appalling sense of waste and, in the end, awe that Hazel inspires. Flannery O’Connor was a Catholic living in the southern US. The characters in this book are all Protestant. Maybe she’s observing them from the other side of a sectarian fence and seeing them as wildly deluded, but the pervasive sense of intractable mystery, of not-knowing, and the lack of overt authorial commentary, makes a sectarian reading seem wide of the mark. I finished the last page with a sense that I’d been taken somewhere dark, weird and scarily believable.

I read Waves as research for work. It reminded me in a roundabout way of an early review of David Williamson’s play The Removalists. As you probably know, in the course of that play, a man – Kenny – is terrorised and beaten up by two policemen. The review I’m thinking of by the late, magisterial H. G. Kippax, found fault with many aspects of the play, including the victimised man being described as a typesetter: according to Kippax, typesetters were not working-class yobbos like Kenny, but quirky individuals who were forever surprising their acquaintances with odd snippets of information. It came with the territory, you see: according to Harry, typesetters read much more widely, if also more shallowly, than normal people who weren’t handling other people’s words for their entire working lives. Like those possibly mythical beings, I often find myself acquiring information about the most unlikely subjects. Waves introduced me to a new world of specialised language: technical language for describing waves and related phenomena (lefties, beachbreaks, righties, peaks and barrels); jargon associated with surfing equipment and practice (coaming, mals, floaters, nosedives, guns); and the argot of the surfing culture, which includes but is not limited to the other two (groms, kahunas, charging and stoked).

The bit I enjoyed most was grand old champion surfer Nat Young’s 1974 encounter with Patrick White (whom Tim Baker describes disarmingly as a ‘gay literary luminary’). After Young is quoted as saying how important The Tree of Man had been to him, we are given this glimpse of Patrick White as filtered through a surfer sensibility:

This unlikely pair discovered they had a connection that went back twenty-five years. ‘He was living down at Werri at that stage, him and his boyfriend, and they were very much in love and they used to spend a lot of time walking on the beach. He said he used to watch surfing and watch waves. Werri, from my childhood, was very important because there was a golf club and it was abandoned and we used to go in and just stay there. And Patrick understood. He said, “Oh, we used to laugh about the way the golf club had turned into a derelict place and the surfers were squatting there on the weekends.” So he knew exactly where my head was at.’

Lawrie & Shirley was a birthday present from my niece Paula.

Somewhere along the line I’ve absorbed, without really noticing it, the notion that poetry should be difficult – if it’s not difficult it’s doggerel; almost: if it rhymes and has a sense of humour, it must be bad. Not that I hold these assertions to be true, but they have insinuated themselves into my brain. But hell, if Lawrie and Shirley is doggerel, then let’s have lots more.

It’s a rhyming narrative, ‘A Movie in Verse’, about a relationship between a man in his early eighties and a woman who’s not a lot younger. Each of its 47 ‘scenes’ opens with screenplay-style directions of the ‘INTERIOR. DAY’ variety, and the story progresses mainly through visuals and dialogue. It’s light, funny, has an unsurprising range of characters (middle-aged children who see their inheritances threatened, disapproving former friends, etc), and manages to feel like an enjoyable romantic comedy, albeit a geriatric one. The great fear that hangs over the characters isn’t death – everyone knows that death isn’t far off – but disability, and more specifically dementia. I wouldn’t say it’s a major focus, but it crops up from time to time. Like this, where Shirley takes Lawrie to visit her aunt Ida in a nursing home – also a nice example of how the jolly dump-de-dum of the tetrameters can tilt over into genuine pathos:

Shirley looks around the room, trying to locate the smile she'll recognise as Auntie Ida's. And finds her after quite a while away off in a distant corner, wasting quietly in a chair, doing absolutely nothing, no recognition in her stare; no smile, no words like 'Hello, Shirley'; no formula like 'Hello, dear'. Shirley stoops to take her hand and, fighting back a hidden tear, sighs to Lawrie, close beside her, 'There's no one in there any more.' Eventually, they turn about and walk back down the corridor. Cross-fade to a final shot of Ida's vacant, lunar face, a kind of undiscovered planet staring coldly into space.

The Book Thief, another birthday present, is a terrific read. I guess it’s a YA title, though some of those famously nervous school libraries might have trouble with the swearing – even though it’s in German, it’s all meticulously translated. The action of the story takes place in a small community near Munich during the Second World War, and is narrated by Death, who doesn’t enjoy his work, is deeply curious about human beings and charmed by them even in the middle of the immense overwork of that period.

Such dark material, but delivered with delicacy, affection and even lightness. Some elements of the presentation might seem irritatingly tricksy to some readers, but they worked fine for me as something like aeration. There are two or three short books, lyrical graphic novels you might call them, within the book, and every now and then a short piece of text is separated from the body and printed in bold type with its own little heading: a key piece of dialogue, some background information on a character, statistics on parts of the war. I read a review somewhere online taking the book to task for trying to exculpate the German people over the murder of the Jews: that’s absolutely not how I read it. These are recognisably human people. They love their children; some take actions, small or huge, against the prevailing Nazis; all of them, willingly or by cruel force of circumstance, are complicit; and all of them suffer. The book has won awards, and it deserved them.

Leonard Cohen’s book is a weirdly mixed bag. There are some memorable serious poems, introspective and embarrassingly honest; and one or two witty throwaways. There are the lyrics of songs, several of which are on his 2004 album, Dear Heather (I’ve just listened to them, and they’re fabulous as songs). But too much of it reads like excerpts from his notebooks – whingeing effusions about being fat, old, failing in love and as a monk, past his prime as poet and singer if he ever had a prime – adorned by innumerable variations on the same gloomy charcoal self-portrait, most of them accompanied by gnomic handwritten annotation. My sense is that if Leonard Cohen wasn’t a celebrity this book wouldn’t have seen the light of day, or at least would have been a much slimmer volume. I suppose we should be grateful that his celebrity status derives largely from his writing! The longing of the book’s title is everywhere, shot through with despair. Frankly, as a preacher in a Peter Cook sketch once said about sex and violence in the movies, we get enough of that at home. When the poem ‘Titles’ asked me:

and now Gentle Reader

in what name

in whose name

do you come

to idle with me

in these luxurious

and dwindling realms

of Aimless Privacy?

I was tempted to reply, ‘G-d alone knows.’ It’s a beautifully produced book, feels good in the hand, and there are some very good things in it. Deeply committed fans will almost certainly love it. I think his editor has let him – and us – down.

Sporadically I continue my way through the Bloom book: Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll made the cut, and make strange bedfellows indeed with Yeats, Hardy and the guy who wrote ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ (‘I have been faithful to you, Cynara, in my fashion’). In his commentary, Harold does seem to like letting us know about intimate or passionate relationships poets have with people of the same gender.

I’ve just started the Heat. Gillian Mears has multiple sclerosis, and some years ago had an unrelated, horrific medical crisis that brought her close to death. When she was securely back from the brink, she bought an old ambulance and set off on a solitary adventure, driving and camping solo for many months. Her account of it is the first article in this issue, and it makes me hope that she has a book in mind: there are Walden-ish moments in the New South Wales bush, House MD-ish urgencies, a beautiful rendering of the way a mind does unexpected things in crisis …

Fragments is the thirteenth book I’ve read as part of the 2016

Fragments is the thirteenth book I’ve read as part of the 2016