Nathanael O’Reilly, Separation Blues: Poems 1994–2024 (Flying Island Poets 2024)

Separation Blues is a selection of poems from Nathanael O’Reilly’s nine previous books, published over 30 years. Each of those books had its own coherence of theme and manner, but this book mostly hangs together beautifully. There’s a bit of whiplash when eight Covid lockdown poems from boulevard (Downingfield Press 2024) are followed by four from Selected Poems of Ned Kelly (also Downingfield Press 2024), which mimic the semi-literate style of the famous Jerilderie letter. But I’m not complaining.

I’m currently reading Arundhati Roy’s memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me. Something she writes (on page 53) seems relevant to these poems:

Maybe it’s best to leave some things un-understood, mysterious. I’m all for the unclimbed mountain. The unconquered moon. I’m weary of endless theories and explanations. I think I have begun to prefer descriptions.

Most of the poems in this collection avoid theories and explanations, or overt expressions of emotion. Most of them describe. Many are structured as lists – of things, people and thoughts encountered while travelling; youthful escapades; political events witnessed. There are a couple of dramatic narratives – a poem’s speaker faints at a service station, and in a different poem he catches fire at a backyard barbecue – but they too have a laconic descriptive air. Even the love poems and elegies, of which there are quite a few, mostly leave their emotional heft to be implied, hovering in the silence around the poem.

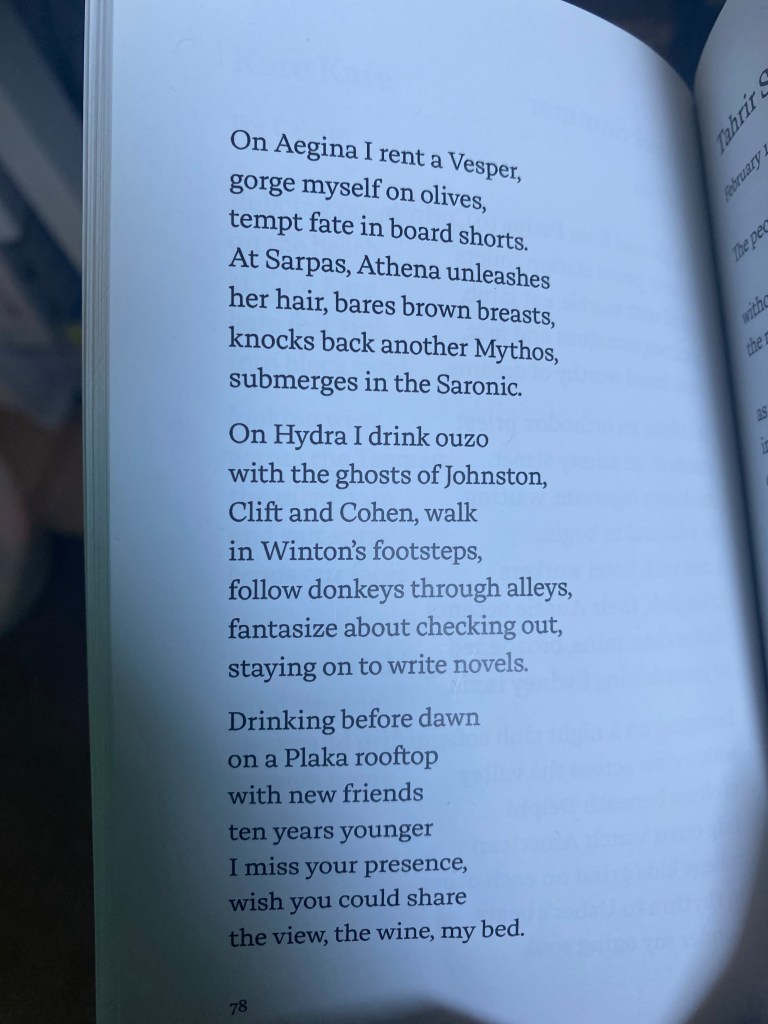

Page 78* is the second page of the poem ‘Greek Summer’.

This is one of five poems in the book with the dedication To Tricia. Some of the others are travel poems featuring ‘we’. ‘Côte dAzur (1905)’, for example, begins ‘During our last childless summer / we lay on the beach at Eze’. In ‘Greek Summer’ the poet travels alone. The first two stanzas on page 77 begin, respectively, ‘On the road from Patras to Corinth’ and ‘In Delphi’, and in the third he is again in Delphi. In those stanzas, he eats, drinks ouzo, performs bodily functions, chats with the locals, notices things – including the strong Australian accents of some taxi drivers, and American college kids who ‘grind on each other’. He ends the third stanza pondering his ageing soul. It’s an impressionistic travel diary.

On Page 78 our solitary poet visits two more islands, and arrives at Athens on the mainland.

First there’s Aegina:

On Aegina I rent a Vespa,

gorge myself on olives,

tempt fate in board shorts.

At Sarpas, Athena unleashes

her hair, bares brown breasts,

knocks back another Mythos,

submerges in the Saronic.

More eating and drinking and mild intercultural discomfort – are board shorts acceptable? At Sarpas Beach, there’s a little poetic playfulness: this is the land of the Ancient Olympians, so when a woman goes topless on the beach, he imagines her as an avatar of Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, and suggests (punning on Mythos, the name of a local beer) that by letting down her hair and baring her breasts she’s knocking back the myth that she, Athena, is aloof, dignified and virginal. He’s enacting the male gaze all right, but not full-on lasciviously. He doesn’t imagine the woman as Aphrodite goddess of love, and the detail of her breasts being brown suggests that his interest is at least partly sociological: this is her usual behaviour at the beach. His gaze is detached, touristic, the erotic element quietly backgrounded.

On to the next stanza and the next island:

On Hydra I drink ouzo

with the ghosts of Johnston,

Clift and Cohen, walk

in Winton's footsteps,

follow donkeys through alleys,

fantasize about checking out,

staying on to write novels.

More drinking. Here, he is a literary tourist, wearing his Australianness on his sleeve. Australian writers Charmian Clift and George Johnston famously did a lot of writing, drinking and fighting on Hydra in the 1960s, some of it in the company of young Leonard Cohen. Tim Winton’s novel The Riders has a sequence on Hydra, in which, if I remember correctly, he rides a donkey on a winding hillside path searching for his wife who has done a runner (and whom he never finds).

As a matter of nerdy interest, this poem appeared in O’Reilly’s 2017 book, Preparations for Departure (UAP Press), before the current resurgence of interest in Charmian Clift and the time Leonard Cohen spent on Hydra. See Nick Broomfield’s Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love (2019), the 2024 Norwegian TV series So Long, Marianne, Nadia Wheatley’s selection of Charmian Clift’s newspaper columns, Sneaky Little Revolutions, or Suzanne Chick’s memoir, Searching for Charmian.

The poet’s fantasy of checking out ‘to write novels’ has the same detached feel as his gaze at ‘Athena’ earlier.

The tourist narrative continues:

Drinking before dawn

on a Plaka rooftop

with new friends

ten years younger

Without breaking a sweat, threads come together. He’s in the Plaka, a neighbourhood near the Parthenon, the ruined temple of Athena, who is now an abstraction, no longer topless with her hair down. Earlier he has watched young people and felt his age, he now drinks through the night with them, but his mention of the age difference here reinforces rather than contradicts his sense of having an ‘ageing soul’.

I miss your presence,

wish you could share

the view, the wine, my bed.

And boom! The poem reveals itself to be a love poem. It’s not a travel diary after all, but a letter home. The details that make up his narrative have been selected with the letter’s addressee in mind. I see young people grinding (and I think of you). I see Athena letting her hair down at the beach (and I think of you). I think of George and Charmian’s relationship (and I think of you), of The Riders (and I think of you).

Many of the poems in this book have similarly unflashy appearances. I don’t know if they all repay close, careful reading as much as this one. I do know that some made me cry. One or two made me gasp. More than one left me pondering a surprising word.

I was searching for a way to finish this blog post, when I came across Anne Casey’s speech launching the book, in the Rochford Street Review (at this link), which includes this:

Here, you will learn of his great loves – gained, lost, and those most closely held. There are elegant elegies – to cherished friends, family, places and times; hymns to eroding ecology and loss of innocence; casually dropped epiphanies; and searing sociopolitical commentary. Small moments provide windows into worlds, slipping through the decades of Nat’s life and his many travels. In this book, he also visits with ghosts of Australia’s troubled settler history.

All true, especially the bit about small moments providing windows into worlds.

I wrote this blog post on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where I saw two sleek crows enjoying the brilliant sunlight this morning. I acknowledge Elders past and present of all those clans, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.

This is a gorgeous book full of dazzling images from Australia’s Central Desert. Its publication coincides with an

This is a gorgeous book full of dazzling images from Australia’s Central Desert. Its publication coincides with an